Zombie Campaigns-to-Be Hold Millions in Cash With Murky Rules

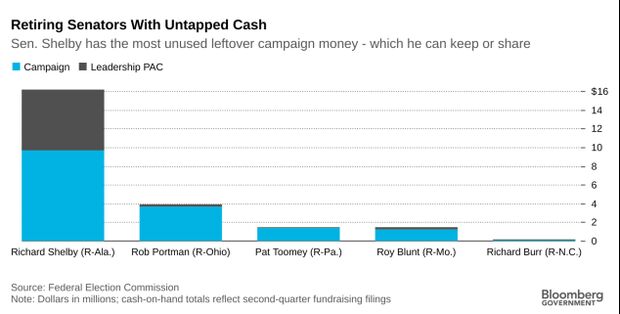

- Shelby’s $16 million in leftover funds the most ever

- Other retiring lawmakers hold $10 million combined

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

As a 34-year Senate veteran who’s chaired four committees and faced little political opposition in Alabama, Richard Shelby has been able to raise millions of dollars more from lobbyists, political action committees, and others with interests before Congress than he’s had to spend to be re-elected.

So with no more races to run, the top Republican on the Senate Appropriations Committee is sitting on more than $16 million in two campaign accounts—far more money than any other retiring lawmaker has ever had. In addition to Shelby, four other current senators and five House members who’ve also announced they’re not running next year for any office have almost $10 million in leftover campaign cash collectively.

Federal law says campaign contributions must be used to run for office or pay for official expenses; “personal use” of the money is barred. But the line between personal and political is getting more blurry, with ex-lawmakers in recent years spending millions to help elect other candidates, including family members, or to fund schools and nonprofit organizations they support.

And if a recent court decision holds up, former lawmakers may even be able to tap campaign funds to repay old personal loans they made to their accounts.

“People just keep pushing the envelope in the face of lack of clarity of the law and lack of enforcement,” said Brett Kappel, a lawyer with the firm Harmon Curran who advises Democratic candidates and other organizations on campaign finance questions.

Many of these so-called zombie committees last for years after the lawmakers who established them left electoral politics or even died, even though the Federal Election Commission has urged them to disburse their money and shut down. Few enforcement actions have been taken, and actual penalties are rare.

Commissioners agreed last year to impose a $15,000 fine and repayment order against former Rep. Cliff Stearns (R-Fla.), but that wasn’t big enough to deter personal use violations, said FEC Democrat Ellen Weintraub. She noted that investigators found Stearns tapped over $26,000 in campaign funds for mobile phone bills, holiday cards, and questionable payments to his wife.

Stearns’s campaign account still holds more than $1.4 million in cash, according to a disclosure report filed July 12, though it’s told the FEC it plans to wind down. The committee has continued paying the former lawmaker’s wife, Joan, $1,000 per month for accounting and bookkeeping, according to the report, and made a $50,000 contribution in June to George Washington University, Stearns’s alma mater.

Personal Use Ban

In an interview, Shelby emphasized that in his early Senate years he supported creating the legal prohibition on personal use of campaign funds. The current provision, which also covers ex-lawmakers, was adopted in 1989.

Shelby holds $9.7 million in a campaign committee and $6.5 million in a leadership PAC he sponsors, according to the latest disclosure reports filed with the FEC. Asked about his own leftover campaign funds, he mentioned contributing to political parties, other candidates, charities, and possibly donating to a university.

“It’ll be done right by the law,” Shelby said.

Shelby said he’s already contributed to Katie Boyd Britt, his former chief of staff, who’s running in a contested Republican primary for the Senate seat he’s vacating. The senator said he “maxed out” to Britt, meaning he gave up to $10,000 if the money came from his leadership PAC. The PAC’s next disclosure report is due by July 20.

Shelby didn’t mention returning the money to campaign donors, and disclosure reports show he’s made few contribution refunds in recent years. In fact, his leadership PAC, Defend America, has continued collecting contributions this year, according to FEC reports, including $30,000 from PACs operated by defense contractors, banks, and other companies.

Most lawmakers say they don’t know the details of campaign finance rules but know there are options besides simply giving money back to donors. Some ex-lawmakers have become lobbyists, using leftover campaign funds to contribute to former colleagues they’re trying to influence—a practice allowed under current rules.

“I haven’t looked at the rules recently,” retiring Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) said in an interview, “but my understanding is they have very strict rules on how you can use” leftover campaign cash.

Portman has recently refunded about $1.3 million to contributors this year but still had $3.7 million in his campaign account at the end of June. He said he’d use the money to contribute to other candidates or nonprofits and that he’s continuing to raise money for a leadership PAC to help fellow Republicans in the Senate and House.

Retiring Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) has refunded $700,000 to donors but had $1.2 million in his campaign account. “I haven’t given it any thought, but we’ll use it,” he said when asked about the leftover cash. “This year we would have used it if I had been running.”

Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.), who’s not running next year, gave $1 million last year to the National Republican Senatorial Committee, taking advantage of a legal provision allowing unlimited transfers to party committees. But, such large party contributions are relatively rare and no other retiring senator has contributed to the NRSC, a review of disclosure reports showed. Toomey has also refunded about $750,000 to contributors but still had $1.4 million in his campaign account.

The only retiring senator without significant leftover money is Richard Burr (R-N.C.), who had less than $50,000 in his campaign account after tapping the fund to help pay legal fees, his disclosure reports showed. Burr was investigated by the Justice Department for alleged insider stock trading based on information gained as a senator, but the probe was dropped earlier this year.

Partisan Divisions

Leftover campaign funds are being used for more purposes partly because of deadlocks between Republicans and Democrats on the FEC over how to interpret and enforce the personal use prohibition.

In one example, Republican Commissioner Sean Cooksey wrote in an “interpretive statement” earlier this year that the prohibition on personal use “does not apply to funds lawfully transferred by an authorized candidate committee after the funds have left the campaign account, and does not apply to other types of non-candidate political committees, including leadership PACs.”

Weintraub has argued, on the other hand, that some personal use restrictions should apply to money from leadership PACs.

Cooksey’s statement could support former Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-Fla.), who transferred leftover campaign money to a leadership PAC when she decided to retire in 2018, after 30 years in Congress. The PAC then paid for a Disney World excursion attended by the lawmaker’s family and for luxury hotels, leading to a criminal investigation.

That was dropped in May by federal prosecutors, according to Ros-Lehtenin’s lawyer, Jeff Weiner. He told Bloomberg Government that the PAC’s payments were for legitimate campaign expenses. Weiner said, however, that an FEC civil enforcement case on the matter remains unresolved. The FEC still hasn’t announced resolution of the case and doesn’t comment on enforcement matters before they are closed.

Read More: Criminal Probe of Former GOP Lawmaker Ends Without Charges

Craig Engle, an election lawyer with the firm Arent Fox and a former FEC staffer who advises Republican candidates and groups, said candidates should still be careful about using funds donated to a campaign account, even if they’re transferred to a PAC.

“The FEC rules do allow, however, former office holders to use left-over funds to pay for politically-related expenses, or expenses that are attendant to having been a Member of Congress,” such as transporting and storing a lawmaker’s papers, Engle said in an email.

Former Rep. Joseph Kennedy II (D-Mass.), who left Congress in 1999 but has maintained a campaign account for more than two decades, tapped the account last year to provide $2 million to a super PAC helping the unsuccessful Senate bid of his son, former Rep. Joe Kennedy III (D-Mass.).

Cruz Case Impact

A court challenge by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) could open up a path for lawmakers to put leftover campaign cash into their own pockets if they’ve lent large amounts of personal funds to a campaign.

In June, a three-judge federal court in Washington, D.C., struck down legal restrictions on the amount and timing of loan repayments to candidates. The ruling has been appealed to the Supreme Court, but if it stands, it could have wide implications, even for lawmakers who left office long ago.

One committee the Cruz ruling could help is that of former Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.), which recently told the FEC it would wind down “once issues related to its outstanding debt are resolved.” The debt involved is more than $1 million loaned to the campaign by Lautenberg nearly two decades ago.

Lautenberg’s campaign account still has about $90,000 in cash, which could be used to pay back part of the senator’s loan. But the money would have to go to his estate. Lautenberg died in 2013.

To contact the reporter on this story: Kenneth P. Doyle in Washington at kdoyle@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Kyle Trygstad at ktrygstad@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.