Women Workers Benefit Most From Home Care Funds in Biden Bill

- Home health-care industry largely employs women of color

- Women’s workforce shrank due to Covid-19, return to office

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Home-based health care should be seen as a jobs program for women of color and a cure for what ails the American economy, supporters of President Joe Biden’s proposal for a massive infusion into the industry say.

Labor groups and key Democratic senators say spending as much as $250 billion over a decade on home health care would create more than 500,000 new jobs in the sector. It would also allow more than a million people to return to work if they previously left the workforce to care for someone with a disability or an elderly family member. The home care industry largely employs women of color, so these new jobs would bolster women’s employment.

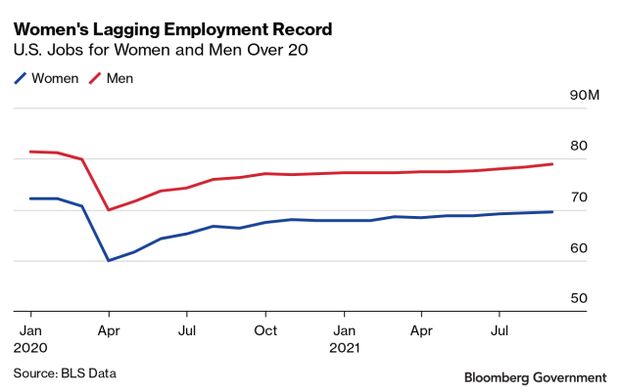

The U.S. economy is ripe for an investment in jobs for women, who have lower employment levels than men and have dropped out of the workforce at higher rates than men since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“This would represent the biggest investment in creating jobs of women and women of color in the history of this country,” Ai-jen Poo, co-founder and executive director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which advocates for domestic workers, said. “It’s what is needed now.”

Democrats are currently debating what to cut from their once-$3.5 trillion domestic spending package to appease moderates like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), who has suggested the package should be as small as $1.5 trillion. Money for home-based health care is among the provisions considered vulnerable.

Democrats Divided Over How Best to Slice Biden’s Economic Agenda

Supporters of home care argue the investment is necessary for the economy and the role women play in it.

U.S. employment has been growing slower than expected in recent months, partly due to women leaving the job market when they were expected to return to work as children went back to school.

The percentage of female workers over 20 who were employed or looking for work dropped to the lowest level since February, according to the most recent data from the Labor Department. Women’s seasonally adjusted participation in the workforce—which represents the ratio of employed and job-seeking people to the total population—dropped to 57.1% in September, from 57.5% in June. Nearly 400,000 women dropped out of the labor force between August and September 2021.

The Latina labor workforce also dropped by 100,000 from July to September, according to Labor Department data.

The home health industry would grow faster if pay and benefits improve as home care services become more widespread, labor groups argue. Home health aides and personal care aides get paid about $12.15 per hour, or $25,280 per year, making it hard to attract new people to the industry.

In many areas, those earnings aren’t enough. Most home health aides qualify for federal help such as food assistance and Medicaid, according to research from PHI, a nonprofit that focuses on direct care workers.

Once home care is established, however, family caregivers have the ability to work outside the home, generating even higher employment across the board.

“We have said over and over again—home care is what makes other work possible,” Liz Shuler, president of the AFL-CIO union, said.

How the Covid-19 Pandemic Created the First Female Recession

Strong Demand

Demand for home health services is already high. Almost 820,000 people in the U.S., most with intellectual or developmental disabilities, were on wait lists to get home- or community-based care through Medicaid in fiscal 2018, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported last year.

Biden originally proposed investing as much as $400 billion in home care. House leaders included $190 billion for home-based care in their version of a massive spending package that encompasses much of the president’s economic agenda. That money would bolster pay for home care workers and expand home and community-based services offered by Medicaid.

Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.) has been pushing for at least $250 billion for home care, according to Democratic aides and a source familiar with discussions. To make his case, Casey has been distributing fact sheets to his colleagues outlining how many new jobs would be created under such an investment.

Biden Home Care Plan Could Fail Without at Least $250 Billion

Casey has been a regular at Senate Democrats’ weekly caucus meetings, pitching home care as an essential investment, according to aides. One point he makes repeatedly is that home care can be cheaper than institutional care like nursing homes.

The U.S. spent $379 billion in 2018 for long-term care services that help seniors and people with disabilities with tasks such as preparing meals, bathing, dressing, and managing medication or mobility, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid paid for more than half of that, which includes nursing home and home health services.

‘Jobs Program’

National labor groups like the National Domestic Workers Alliance and Service Employees International Union organized a rally in Phoenix on Oct. 13 to urge the state’s congressional delegation to support an investment in home care, hoping to win over key lawmakers, namely Sen. Krysten Sinema (D-Ariz.). A main part of their message was that home care creates jobs.

“Medicaid is a jobs program,” Poo said.

Whether a major investment in Medicaid will actually translate to an increase in home care jobs and better pay for these jobs will depend largely on how individual states use the money, Regina Shih, a senior policy research at the RAND Corporation who studies home care, said.

Under a bill proposed by Casey and other Senate Democrats (S. 221), states could see the federal share of their Medicaid budget increase significantly in exchange for increasing what they pay home care workers and investing in career training and support for home and community-based care programs.

States run their own Medicaid programs with federal oversight and investment, so they differ in how much they spend on home care versus institutional care, Shih said. States that have already spent heavily to expand their home care workforce would benefit the most from a massive increase in federal dollars, while those that haven’t would struggle to catch up.

“It’s going to be up to states to take advantage,” she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Ruoff in Washington at aruoff@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Fawn Johnson at fjohnson@bloombergindustry.com; Sarah Babbage at sbabbage@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.