‘What Do You Need?’ Trump Asked, and $1 Billion Vessel Followed

- Russia, China step up commercial, military presence in Arctic

- Inauguration Day pitch overcomes decades of Washington inertia

Admiral Paul Zukunft found himself next to Donald Trump on the presidential inauguration parade route on Jan. 20, 2017. The president asked the Coast Guard commandant whether he had everything he needed. “No, sir,” Zukunft replied.

“What do you need?” Zukunft recalls Trump asking. “I need icebreakers,” he said.

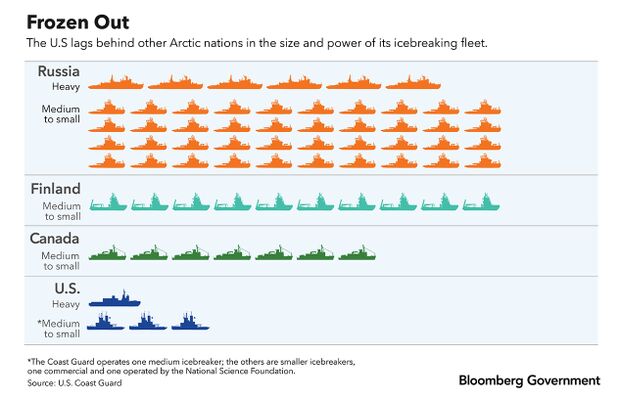

More than a year later, the Coast Guard has started a competition to build the first new heavy icebreaker cutter for the Arctic and Antarctic after decades of neglect. Russia and, increasingly, China have expanded their polar presences while the U.S. currently has only one 40-year-old heavy icebreaker as lawmakers weighed costs and other priorities.

Much rests on the U.S. ability to send a new icebreaker to the resources-rich high latitudes: the proposed ship, which would be able to cut through 21-foot-thick ice, is becoming a symbol of American presence and power in the Arctic in the absence of a clear national strategy to defend U.S. interests there. Without a new icebreaker, proponents say, the U.S. risks being caught empty-handed in a region where Russia has expanded its reach and rebuilt a military arsenal while the relationship between the two countries has deteriorated.

“If we don’t have an icebreaker, we won’t be able to be at the table,” Rep. Duncan Hunter (R-Calif.), an early and vocal supporter of new icebreakers, said in a telephone interview.

“You don’t know what is coming, and we are always wrong,” Hunter said.”We never guess where the next war is and how it is going to be fought. You have multi-pronged reasons to want to be in the Arctic, even just to be there and be seen.”

The interest in the $1 billion vessel among the shipbuilding industry is high. The Coast Guard last February awarded five firm-fixed-price contracts for heavy polar icebreaker design studies and analysis to Bollinger Shipyards, Fincantieri Marine Group, General Dynamics’ National Steel and Shipbuilding Company, Huntington Ingalls Industries Inc., and VT Halter Marine.

The lag in U.S. power in the Arctic isn’t for lack of effort. “We have been working this going on two decades now and we worked with various administrations over time,” Zukunft said in an interview with Bloomberg Government in Washington. “We didn’t really have a way ahead for the Arctic region. At the same time, we’d see, year after year, sea ice retreating and we have an ocean open up into what we call a ‘strategic vacuum.’”

Russian Ice Dreams

Russia’s top-of-the-world profile is vast: It has the world’s longest Arctic border, stretching more than 10,000 miles and spanning from the North Cape to the Barents Sea. The U.S., by contrast, occupies only 4 percent of the land above the Arctic Circle. Russia and Canada, combined, have 80 percent of that land.

Russia has a fleet of about 40 icebreakers, with more coming online. It is also the only country to build massive nuclear-powered icebreakers that can stay at sea for longer periods of time than their conventional counterparts. What’s more, Russia has military bases, deepwater ports and air bases in the Arctic Circle.

With access to the region’s oil, natural gas and mineral resources at stake, Russia is preparing for the possible militarization of the Arctic, U.S. officials say.

Russia is now looking at putting icebreaking corvettes with cruise missiles up in the high latitudes, “and we are starting to see a militarization of the Arctic at the same time,” Zukunft said. The Coast Guard, a military service under the Department of Homeland Security, will leave room in the design of the new icebreaker for weapons as well, Zukunft said.

This isn’t the Coast Guard’s “first approach, to turn this into an icebreaking dreadnaught,” he said. Should tensions escalate, the service is reserving the space, weight and power for the ship to carry weapons, Zukunft added.

Polar Silk Road

Another major U.S. strategic rival — China — is steadily growing its presence there. China calls its vision for the Arctic the “Polar Silk Road” for shipping goods to Europe, part of the Asian country’s sprawling foreign policy initiative known as the Belt and Road initiative.

“What we need to be is vigilant to what a more Chinese commercial and economic presence in the Arctic means,” as it lays undersea cables, digs mines and builds railroads, said Heather Conley, senior vice president for Europe, Eurasia and the Arctic at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. .

While Arctic international competition is heating up, Conley warned against making too much of the comparisons between the U.S. and Russian icebreaking capabilities.

“The Russians have a different economic model and 50 percent of the coast line,” she said. “If all you do is compare to someone else, you are not answering the question what do we need.”

And Zukunft said the Coast Guard and the Russians have found ways to work together in the high latitudes.

The Coast Guard has “a very unique relationship” with the Russian border service, he said. When the Coast Guard did the largest search and rescue exercise in the Arctic in September in Iceland, Russia was there. Russia also participated in the Arctic Coast Guard forum, he added, and helps curb illegal fishing.

Big Test

While Russia and China made investments to exploit the Arctic, the U.S. government was unwilling to fund a new heavy icebreaker. That may be changing.

“Right now, we have finally arrived at a juncture where everyone is all in on, `yes, we must have icebreakers’,” Zukunft said.

Focusing on the Arctic “has to be a national imperative,” said CSIS’s Conley. “We are using very precious national resources and we need to know what would give us the biggest bang for our buck.”

For the Coast Guard, one of the challenges is simply the size of the project. For the new icebreaker, the Coast Guard has partnered with the Navy to benefit from the Navy’s expertise and industry connections in building large ships. On March 2, the two services issued a request for proposals for the design of as many as three heavy polar icebreaker cutters. A single contract will be awarded in 2019.

The cost of the first new heavy icebreaker is estimated to be about $1 billion, though the Coast Guard is aiming to come below that, Zukunft said. The Coast Guard has projected needing at least three heavy icebreakers, with the cost per ship coming down down after the first is built, he said.

The Coast Guard requested $750 million for the icebreaker in fiscal 2019. Together with a congressional addition of $175 million for the program in 2017, and some more possibly this year, the service will have enough money to pay for, at least, its first new icebreaking cutter.

President Barack Obama in 2015 called for speeding up the timeline for buying new icebreakers. Obama wanted to see the new icebreaker in the water by 2020, but current estimates put the delivery of the first ship in 2023.

An Unfixed ‘Star’

Meanwhile, the service’s only operational heavy icebreaker cutter has been afloat near the South Pole.

The Polar Star, built in 1976, departed its home port of Seattle Nov. 30, 2017, and is expected to return to the U.S. this month. The vessel’s main mission has been to cut a path through the ocean ice – often 10 feet thick – to an ice pier that serves the U.S. Antarctic Program’s McMurdo Station. The Polar Star assists in the annual delivery of operating supplies and fuel for the National Science Foundation research stations in Antarctica during Operation Deep Freeze.

The 399-foot vessel has a crew of about 150, weighs 13,500 tons and uses 75,000 horsepower that can break ice up to 21 feet thick. Yet in January, the cutter had to overcome flooding and a failed gas turbine engine.

If Polar Star breaks down, “strategic investments would go away,’’ Zukunft said. “We are not going to be leasing Russian icebreakers anytime soon with the world tensions being the way they are right now.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Roxana Tiron in Washington at rtiron@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jonathan Nicholson at jnicholson@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com