Veterans Service Dog Program Stymied by Disputes on Rules, Money

- Supporters cite high rates of suicide, PTSD for veterans

- VA says law didn’t authorize it to fund program startup costs

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to grow your opportunities. Learn more.

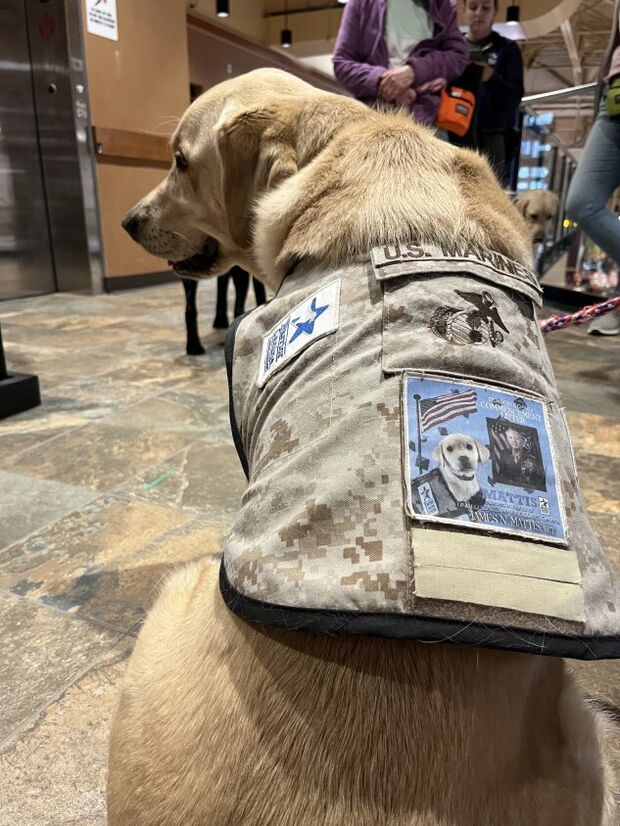

Two years after Congress directed the Veterans Affairs Department to integrate service dogs into its treatment programs, the $10 million initiative has been hamstrung by disputes over funding, regulation, and whether it will make a difference for traumatized veterans.

The 2021 Puppies Assisting Wounded Servicemembers Act approved the pilot program at five VA medical centers in California, Alaska, North Carolina, Florida, and Texas. But the VA has not allocated any money to subsidize the startups, leaving the service dog providers and trainers to foot the bill.

A spokesperson for the VA told Bloomberg Government the PAWS Act was unfunded and that the service dog organizations agreed to participate as an “in-kind service” for veterans. The agency also pointed to unsettled questions about the effectiveness of the treatment; a separate Defense Department entity has cited a lack of industry standards or regulation.

The VA is using “administrative double talk to avoid a law that Congress passed,” said former Rep. Steve Stivers (R-Ohio), now an officer in the Ohio National Guard who was decorated for his service in Iraq and sponsored the legislation.

The agency declined to respond to Stivers’ criticism.

But the pilot project’s slow implementation highlights the occasional mismatch of programs approved by Congress and the ability of federal agencies to execute them.

What’s not in dispute is the need to help veterans. One-third of those who served in Iraq or Afghanistan have been diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a traumatic brain injury, or depression. An average of 16.8 veterans each day died by suicide in 2020, a rate much higher than the general public, according to a VA report.

Uniformed Services University, the Pentagon’s training ground for medical professionals, is now trying to enlist the private sector to draw up new standards and regulations to govern an industry that contends it already had them in place—something that the PAWS Act recognized.

“We continually fight an uphill battle getting the VA to utilize service dogs as part of what their response to PTSD is,” said Damian Cook, director of policy and government affairs for K9s For Warriors, a Florida-based group that calls itself the nation’s largest service-dog provider to veterans. “They won’t do that, but they’ll put warriors on drugs.”

An Ongoing Debate

The debate stretches back more than a decade. In 2010, as concerns swelled about soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, the VA undertook a congressionally mandated study to research the impact of service dogs on traumatized veterans. It was halted a couple of years later—after dogs bit two children and concerns arose about training and health problems of participating dogs—but it restarted in 2016.

At that point, the agency chose to focus its study on the differences between veterans who use service dogs and those who have emotional support dogs. Service dogs are trained to perform one or more tasks for people with disabilities. Emotional support dogs are viewed more often as pets designed to comfort and calm their owners.

There are also legal ramifications distinguishing the two. Service dogs are allowed in most public places, including VA hospitals and clinics, while emotional support dogs are not.

In January 2020, the VA released results of a study that found no notable difference in the overall disability and quality of life between veterans who had a service dog and those with an emotional support animal. The same study did find that service dog owners displayed fewer PTSD symptoms and suicidal behaviors.

Private research funded by the National Institutes of Health and conducted by Kaiser Permanente and Purdue University has also pointed to the mental health benefits of providing veterans with trained service dogs. Researchers cite lower cortisol levels—a stress biomarker—as well as improved interpersonal relationships, better sleep, and fewer symptoms of PTSD and depression.

Another VA study, this one released in 2021, concluded that service dogs didn’t significantly reduce or change treatment costs for traumatized veterans.

That year, the PAWS Act sought to speed up the process of connecting veterans with service dogs by directing the VA to contract with existing organizations in the field.

But like a decade ago, questions surfaced about training and standards.

A study managed by the Uniformed Services University found “no required standards or outcome measures” in the service dog industry. “The lack of shared guidelines makes it difficult to evaluate the quality of service dog programs because this quality was never defined,” it concluded.

The USU said it drafted benchmarks for a contractor to test, validate, and improve upon.

The USU has not publicly released its study. But its desire to build standards now includes the Medical Technology Enterprise Consortium, a group representing private government contractors, which sent out a solicitation in March for help developing the benchmarks. The government, it said, had up to $15 million available for awards just this year.

Cook’s group, K9s for Warriors, helped establish the Association of Service Dog Providers for Military Veterans, which has standards on dog selection and training, veteran matching and training, and follow-up services. The VA had already recognized “the expertise and national scope” of other umbrella groups, such as Assistance Dogs International and International Guide Dog Federation, which certify smaller organizations in training standards.

Cook said his program has paired more than 850 veterans with service dogs and lost just three service members to suicide. Those numbers show just how effective service dog therapy is, he contends.

“Even if service dogs don’t have the clinical evidence that pharmaceuticals do, they also don’t have the negative side effects,” Cook said.

‘This Dog Saved My Life’

Cyndi Hunt, 64, from Niagara Falls, N.Y., spent 35 years suffering from PTSD after being sexually assaulted in the Navy, she said.

Hunt said she couldn’t leave the house, hold down a job, maintain relationships, and she eventually found herself homeless in 2017. Her psychiatrist finally persuaded her to try a service dog, so she adopted a Doberman named Anubis.

“I would have to say the psychiatrist was right. This dog saved my life,” Hunt said. “Not only is he my companion, but he’s also the guy that can tell if I’m going to have a panic attack before I know.”

When those symptoms emerge, Hunt’s dog forces her to sit down and wait for it to pass. He’s even awakened her with kisses when she’s having a nightmare.

Hunt said the VA could do more for veterans with service dogs by providing funding, directions on where to find funding, or facilitating a support group for veterans to talk about problems with dog training or how to interact with the public.

“Sometimes we need the VA because we don’t feel like we’re legitimate,” she said. “We just need that military backing to say, ‘Yes, you’re doing the right thing. Yes, you’re on the right track.’”

‘Really Powerful’

Rick Yount, a former social worker, has advocated for service dogs for veterans as far back as 2008, when he established a partnership with the VA for a training program in Palo Alto, Calif.

These days, he runs the Maryland-based Warrior Canine Connection, about 30 miles northwest of Washington D.C. On a swath of green public lands surrounded by hiking trails and farms, he breeds and trains dogs like the group of two-week-old golden retriever puppies who huddled there last month, sleeping snout to snout.

Huggable as they might be, the dogs do much more than just distract or soothe their owners. A commonly cited benefit by service dog organizations is the dogs’ ability to help veterans stay “present” by nudging or licking them when they face vivid flashbacks or emotional triggers in public.

“I don’t know [that] there are any pills to help people integrate back into the community and strike up conversations with civilians,” Yount said after cradling a month-old puppy. “I can tell you that the dogs are really powerful at that.”

Yount estimates that a yearly appropriation of $10 million over five years could serve nearly 20 program sites and at least 40,000 veterans struggling with PTSD. But first it needs to get off the ground. Around 130 veterans are expected to participate in the VA program this year.

“The wait list is way too long. My hope is that this will help to address that and do it soon because we have a national kind of crisis with veterans,” Yount said. “I mean, dogs aren’t for everyone, but man, they are incredible in what they can do for mental health.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Patty Nieberg in Washington at pnieberg@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Amanda H. Allen at aallen@bloombergindustry.com and John P. Martin at jmartin1@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – the intel you need to win new federal business – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.