Unions Growing Among Democratic Political Campaign Staffers

- Outreach has increased, campaign workers guild says

- Additional protections are needed in industry, staffers say

A political campaign seems an unnatural place for a union: It’s a temporary environment where staffers — fueled by larger ideals and trust in a candidate — are expected to work long hours for little pay until Election Day.

Yet, unionized campaigns are increasing among candidates at multiple levels. Staffers unionized in nearly every serious Democratic campaign for president — including nominee Joe Biden. The trend is catching on down-ballot as well, with several House and Senate races organizing unions.

Since helping organize the first House campaign union in 2018, the Campaign Workers Guild has negotiated 51 contracts as of this month, said Julia Ackerly, the group’s vice president and a former campaign worker. All are Democratic campaigns.

“Working conditions are notoriously bad for campaign workers,” Ackerly said. “The idea was to bring transformational change to the industry by unionizing campaigns.”

Still Uncommon

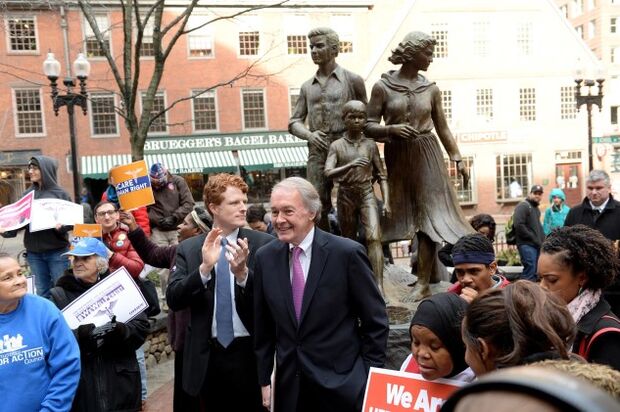

There is no public data on how many campaigns have unionized their staffers. But the list includes a number of prominent candidates, including Rep. Joe Kennedy III(D-Mass.) and the incumbent he’s challenging in a primary next week, Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), as well as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.).

Smaller campaigns have unionized as well, including Mike Siegel’s. He’s the Democratic nominee in Texas’ 10th District against Rep. Michael McCaul (R).

“The more this gets publicized and the stronger these campaign worker unions get, the more it will become an accepted way of doing business,” Siegel said. “It’s going to increasingly become a thing where you’re expected to recognize a union for their campaign staff.”

This is the second election cycle Siegel’s staff has been organized. Other House campaigns with unions include Reps. Deb Haaland (D-N.Mex.), Max Rose (D-N.Y.) and Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.)

Still, unionization of campaigns remains uncommon, even among candidates who tout pro-labor stances.

Part of the reason is that it’s still a new concept, Ackerly said. But there’s also some resistance to the idea that the fast-paced, do-or-die world of campaigns has room for staffers to stand up and ask for fewer hours and more pay.

“There is this campaign culture that is really embedded where setting up workplace protections during a really intense and urgent timeline on a campaign just gets pushed to the back burner,” she said. “A union contract is an interruption of the status quo.”

Tough Conditions on the Trail

When Ian Russell first began working on campaigns in the early 2000s, he took pride in the long hours he worked with a salary that called for couch surfing and few extras.

But these days Russell, a Democratic campaign consultant, advises younger operatives to ask for more pay. The Democratic Party, he said, has “had a reckoning with the fact that often times people from middle class or more privileged families are the only ones able to take jobs like that.”

“Who can afford to take a semester off of college to knock doors for their chosen presidential candidate in Iowa if they have to have a job flipping burgers to make ends meet?” he asked.

Janice Fine, who studies unions at Rutgers University’s Center for Innovation in Worker Organization, said the rise in unions is coming with new mindsets about work-life balance from the next generation of campaign staffers.

“What’s changed is a combination of a new generation that’s been really interested in unions and that same new generation is more focused on work-life balance,” she said.

Benefits

Contracts for campaign staffers differ in what benefits they offer, but some common ones include minimum wage and health care, as well as ensuring workers won’t be stiffed on their final paychecks after the election.

Other benefits include giving staffers windows of time where they can take days off and reimbursement for cell phones, mileage, public transit and travel.

Ocasio-Cortez’s campaign negotiated a 40-hour work week. That might not be possible for other campaigns, said Garrick Trapp, who works on the campaign’s policy team and was part of the bargaining unit, but asking for a cap on hours “forces management to really be more critical and decisive in how they want to use their work.”

Unions also give staffers a place to turn to fight back against harassment within campaigns. In 2016, aides from Sen. Bernie Sanders’ (I-Vt.) presidential run were accused of sexism and sexual harassment. In 2020, Sanders’ became the first presidential campaign to unionize.

“Having really powerful people involved can lead to protection of bad actors,” said Jacob Aronowitz, one of the founders of United Professional Organizers, which works mostly in Texas to help campaign staffs, such as Siegel’s, unionize.

‘This Movement Will Grow’

While Russell is supportive of staffers seeking to unionize, he also acknowledges it can be challenging given most staffers are working for 18 months or less.

“The economics of this have not evolved to the point where this is a topic of widespread conversation amongst young campaign operatives,” he said, noting it’s easier for presidential and state parties to unionize rather than a smaller campaign with few staff and a tight budget.

The issue of time is being partially alleviated as more campaigns undergo the process. Some campaigns that unionized in 2018, such as Haaland’s, are reusing the contract from that election in 2020. Kennedy’s staffers looked to Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s and Pete Buttigieg’s presidential campaign unions, said Kennedy campaign spokesman Mike Cummings. That helped the entire process, including negotiations, take only a few weeks.

“When we decided that we wanted to unionize, we replicated what we saw in the Warren campaign and the Pete campaign when they unionized,” Cumming said. “It made for a simple process for us.”

Still, one lingering issue that could keep unionizing campaigns from growing faster is that it runs counter-intuitive to the internal pressure staff feel to give everything they’ve got toward a candidate they believe in, Trapp said.

“The purpose of the campaign is to get someone elected,” he said. “And so in some ways there’s always a guilt if you’re not doing something 24/7 to get that person elected.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Emily Wilkins in Washington at ewilkins@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergtax.com; Kyle Trygstad at ktrygstad@bgov.com