Uber, Lyft Influencers Find Democratic Allies Toughest to Sway

- Ridesharing gears up to defend business model at federal level

- Company goals at odds with Democrats’ traditional stances

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

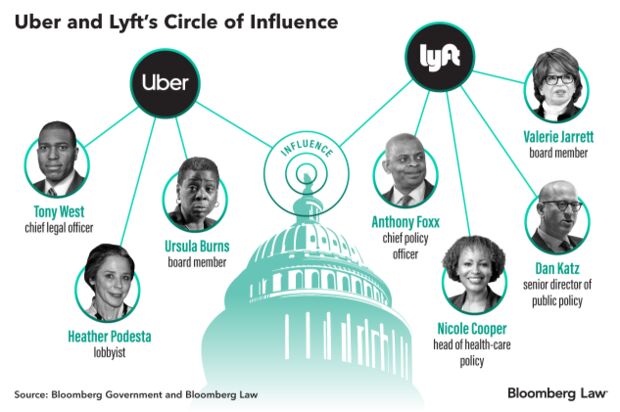

With their business model threatened in the courts and several states, Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. have assembled all-star casts of connected Democrats to convince Congress and regulators to not classify their workers as employees.

Influence campaigns in Washington don’t normally target the party that spends most of an administration in the political wilderness. But the onslaught of people and money reflects that Uber and Lyft’s obstacles aren’t from President Donald Trump’s Republican administration, but from Democrats, particularly if there is a power shift ahead in the White House.

The companies’ goals go against Democrats’ traditional labor allies, even pitting vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) on the opposite side of her brother-in-law, Tony West, Uber’s chief legal officer. The strategy has been more about containing damage than claiming victories.

“It’s really sad, a lot of the politically-engaged staff who have gone to work with Uber are now making the argument that we’re hearing called for from Trump,” said Shannon Liss-Riordan, a lawyer who represents ridesharing drivers and other gig economy workers. Liss-Riordan dropped her bid for a U.S. Senate seat this year.

Lyft recruited Anthony Foxx, President Barack Obama‘s transportation secretary, as its policy chief two years ago this month. Foxx’s former chief of staff Dan Katz is now Lyft’s senior director for public policy. Lyft hired Nicole Cooper, a Department of Health and Human Services appointee during the Obama administration, in July to handle health-care policy. And Valerie Jarrett, a longtime Obama adviser, has been on Lyft’s board of directors since 2017.

“Lyft has assembled a team of leading policy experts in order to be a leader in conversation around the future of transportation and the future of work,” said Julie Wood, a spokeswoman for the company, about hiring top Democrats. “We’re deepening our understanding of these complex issues and creating forward-looking solutions that can help solve some of the challenges facing our cities.”

Uber’s board includes former Obama advisory council member Ursula Burns. The company previously employed former Obama campaign manager David Plouffe as head of policy and strategy. Heather Podesta, a Washington lawyer and lobbyist with strong Democratic ties, has lobbied for Uber since 2017.

Uber and Lyft claim their drivers are independent contractors who aren’t eligible for benefits. But the two San Francisco-based companies have also sought a new worker category that revolves around offering portable benefits, or those that carry over from job to job, as a tradeoff for continuing to classify their workers as contractors.

Anything else at the federal level could add hundreds of millions of dollars in employment costs for companies already hit hard by the financial fallout from the coronavirus pandemic.

“For the last century we’ve lived with a legal framework that’s created two classes of workers: employees and independent contractors,” West said at an October Bloomberg Law event. That framework has become increasingly untenable for Uber, Lyft, and other technology companies, leading them to seek a third way that preserves key elements of the “flexibility that gig work offers,” West said.

Paying to Play

Uber and Lyft are mostly focused on state-level fights, the most prominent of which is now the most expensive ballot initiative campaign in California history. The ridesharing giants and other gig economy companies are seeking to overturn a law, A.B. 5, which made it difficult to use independent contractors.

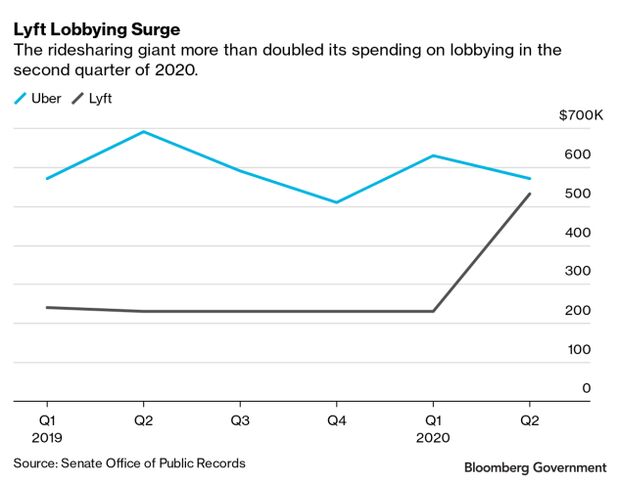

But Lyft has also poured new resources into federal lobbying, even with its business hurting from the pandemic. Senate records show Lyft’s lobbying spend increased 130% year-over-year in the second quarter. Lyft launched a political action committee in April, Federal Election Commission filings show.

Lyft co-founders John Zimmer and Logan Green have together donated at least $100,000 to a group hoping to build a Democratic majority in the Senate, according to FEC records as of late September.

Wood, the Lyft spokeswoman, said the company “believes it is important to engage in the political system in order to advocate on the issues that reflect our values and that impact both our riders and our drivers.”

Lyft has also tapped a pair of well-connected Republicans from the law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld in Washington as outside lobbyists: G. Hunter Bates, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell‘s (R-Ky.) former chief of staff, and Brendan Dunn, a former McConnell adviser who worked on the 2017 tax law (Public Law 115-97).

Uber spent about $2.3 million on federal lobbying in 2019 and $1.2 million through the second quarter of 2020, according to Senate records. While Uber executives generally don’t donate to individual candidates, according to FEC records, Danielle Burr, the company’s head of federal affairs, has given more than $20,000 this election cycle to benefit her former boss, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), and Republican candidates.

West has contributed at least $5,000 this year to Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden‘s campaign and other Democratic campaigns, according to FEC records. Chris Pangilinan, Uber’s chief public transportation policy advocate, co-hosted an October fundraiser for the Biden-Harris ticket.

Uber employees have also overwhelmingly donated to Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) this election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Democratic Divide

The cadre of politically connected Democrats help Uber and Lyft market themselves to lawmakers as fundamentally different than other companies, and thus deserving of special status under federal employment law.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Sanders have been among the more vocal backers of state legislation designed to force companies to classify workers as employees.

“There’s a difference in the Democratic Party over how they view this issue,” said Brian Chen of the National Employment Law Project, which supports workers. “For some, there’s a clear picture of worker exploitation and for others, they really have been convinced by the companies’ narrative that this is flexible work.”

Biden said in May he supports the new California law requiring companies to provide more benefits to app-based workers.

West, in an interview for a future Bloomberg Law podcast,said he doesn’t discuss Uber issues with Harris.

In the Bloomberg Law event this month, West noted he sees the worker classification debate as one that will ultimately be determined by voters, many of them Democrats, who he said are in favor of the flexibility offered by an “independent work” model with protections such as health benefits and minimum earning standards.

“People take positions without having an honest conversation about how to make things better,” he said.

Though generally opposed by progressives, the portable benefits concept has backing from other factions within the Democratic Party.

The New Democrat Coalition, a caucus led by Rep. Derek Kilmer (D-Wash.), released policy recommendations on portable benefits in 2018. Other supporters include Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.), a former technology executive turned legislator, and Rep. Suzan DelBene (D-Wash.), who have introduced bills that would test out portable benefits.

“We focused on having state and local government innovate here, so that they can work closely with workers,” DelBene said. “Then, we can come up with what type of federal model there should be.”

Green, Lyft’s co-founder, and Foxx, Lyft’s policy head, had both donated money to support Warner’s reelection campaign as of late September.

Devil in the Details

The ridesharing giants have persuaded lawmakers to put language friendly to their industry into proposed legislation, slowly making their case that gig workers should be in a separate category.

One example is when Congress granted Uber’s request to set aside pandemic unemployment aid for gig workers in a March law. Independent contractors are generally excluded from unemployment assistance.

Senate Majority Whip John Thune (R-S.D.), one of few Republicans to receive a personal donation this year from Lyft’s Green, introduced a bill (S. 700) that would create a pathway for gig workers to be classified as independent contractors while lowering the revenue threshold for Uber and Lyft to issue a form that helps drivers correctly file their taxes.

Lyft has retained former Thune tax counsel Paul Poteet, who now works at Washington-based lobbying firm Glover Park Group, to lobby on tax issues affecting transportation network companies, according to Senate records.

But with no Democratic cosponsors, Thune’s bill is unlikely to become law during this Congress.

Looking Ahead

Uber’s and Lyft’s wins have been mostly due to Republicans and the Trump administration. It remains to be seen how long those victories will last.

The Labor Department released a rideshare-friendly proposal in September that would make it easier for businesses to classify workers as contractors instead of employees. The National Labor Relations Board general counsel’s office said in a 2019 memo that Uber drivers aren’t legal “employees” for the purposes of federal labor laws.

As the California ballot initiative looms, Uber’s top lawyer, West, said the company is thinking hard about the “different eventualities” it faces. He said one option is to pull out of the Golden State altogether, but added that the company will comply with the law, whatever that may be.

One eventuality Uber and Lyft have been planning for is not having drivers at all. They, along with others in the development of autonomous vehicles, have had little success getting a federal regulatory framework for the technology that could provide an exit for their labor issues.

Despite circulating multiple drafts, lawmakers in the House and Senate have yet to introduce a bill on the subject this Congress. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has produced no regulations on self-driving cars since issuing its first voluntary guidance four years ago.

In the near term, how Uber and Lyft shape the worker classification issue will affect other technology companies that rely on gig workers.

“I don’t think Uber and Lyft are going to be around forever,” said Caroline Bruckner, a professor at American University who has studied tax issues among gig workers. “The model they’ve developed might be.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Courtney Rozen in Washington at crozen@bgov.com; Brian Baxter in New York at bbaxter@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Chris Opfer in New York at copfer@bloomberglaw.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.