Test Tube Burgers Prompt Regulators to Beef Up Safety Oversight

- Technology breakthroughs confront outdated food regulation

- Lawmakers wary about shared regulation of cell-cultured foods

A Dutch start-up called Meatable thinks it has a game-changing product that can help feed a crowded, hungry world: laboratory-grown hamburgers.

Enthusiasts say large-scale production of lab-cultured meat would use 90 percent less land and water than conventional farming and could revolutionize agriculture while addressing global warming and rising worldwide demand for protein. Consumers will have two big questions. Are test-tube burgers tasty? And are they safe?

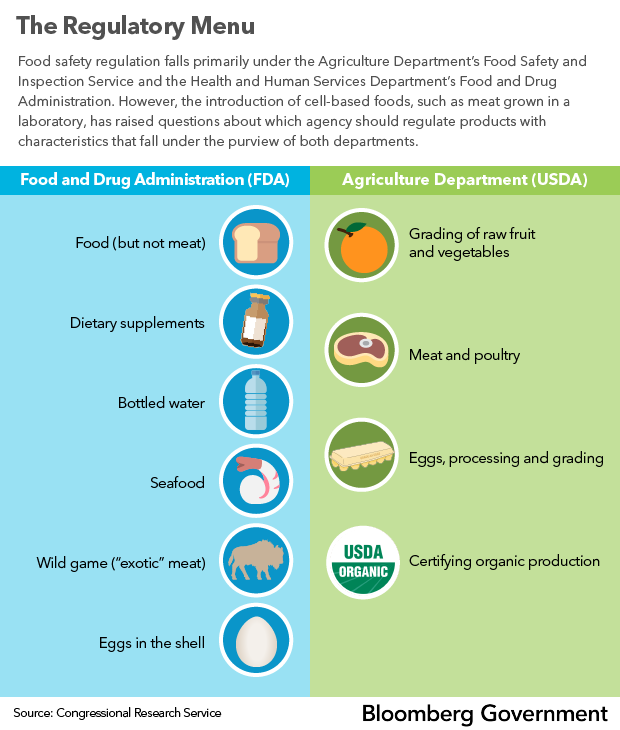

Answering the second question is already forcing U.S. regulators to weigh big changes to the fragmented, archaic food-safety regime, as they race to keep up with technological breakthroughs that are blurring jurisdictional boundaries.

Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue and Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb announced in November a deal to share jurisdiction, with the FDA overseeing the process of growing cells in the laboratory and the USDA supervising production and labeling. Meanwhile, a White House government reorganization plan blueprint released last summer sets a more ambitious goal of creating a single agency within the USDA to regulate food safety.

California-based Memphis Meats Inc. — a lab-grown meat startup backed by high-profile investors including Bill Gates and Richard Branson, as well as conventional meatpackers like Tyson Foods Inc. and Cargilll Inc. — welcomed the joint announcement as a “clear path to market for cell-based products.”

“This regulatory framework plays to the respective strengths of both USDA and FDA, while continuing to foster innovation and assure a safe and reliable food system,” Memphis Meats co-founder and CEO Uma Valeti said in statement.

‘TALK IS CHEAP’

Ranchers and meatpackers subject to USDA regulation expressed satisfaction with joint USDA-FDA regulation. Danielle Beck, government affairs director for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, said the USDA will take the “primary role of ensuring that lab-grown meat is held to the same food safety and labeling standards as real beef.”

But Robert Aderholt (R-Ala.) wants to see how the shared regulation would actually work before endorsing the concept, Chief of Staff Brian Rell told Bloomberg Government. The House fiscal 2019 Agriculture Appropriations bill (H.R. 5961) would require the USDA to take the lead role in regulating lab-cultured meats but the USDA is among the departments left unfunded in the partial government shutdown.

“Chairman Aderholt would like to see more progress in finalizing the Memorandum of Understanding and along the outlines established in the joint press release,” Rell said. “Talk is cheap when written words matter in jurisdictional battles.”

SAFETY EVOLUTION

The U.S. food-safety system is rooted in the Progressive movement of the early 20th century, when muckraking journalists like Upton Sinclair stirred up public outrage about unsanitary conditions in the meatpacking industry. The revelations led to enactment of the Meat Inspection Act, which requires the USDA to inspect all livestock and poultry for human consumption, and the Pure Food and Drug Act, which bars the manufacture and sale of of adulterated or misbranded foods, drugs, medicines, and liquors. President Theodore Roosevelt signed both bills into law on June 30, 1906.

The USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service evolved as the regulator of meat and poultry safety, while the Food and Drug Administration was later created to police the Pure Food and Drug Act. Over the years, the number of agencies with some role overseeing food safety mushroomed. By 2011, the Government Accountability Office reported there were at least 15 federal agencies collectively administering more than 30 food-safety laws.

President Barack Obama joked about this complexity in his 2011 State of the Union address. “The Interior Department is in charge of salmon while they’re in fresh water, but the Commerce Department handles them when they’re in saltwater,” Obama said. “And I hear it gets even more complicated once they’re smoked.”

POLITICAL OBSTACLES

Thomas Gremillion, director of food policy for the Consumer Federation of America, said the Trump administration proposal to create a single food-safety agency will probably run into the same political obstacles that defeated previous efforts.

“It’s such a sweeping reform that it inevitably challenges some vested interests, including the agencies themselves, who do whatever they can to keep serious proposals off the table,” he said.

Val Giddings, senior fellow at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, told Bloomberg Government a consolidated food-safety regulator isn’t necessarily better for consumers and food producers.

“This will not happen overnight and there are more ways to mess it up than get it perfect,” he said.

HAZY JURISDICTION

Products like lab-grown meat further cloud the lines of jurisdiction.

Meatable promises that after an initial three-year research and development process it will be able to make hamburger meat in a lab from bovine stem cells in three weeks. The company boasts that its process could produce enough hamburger from a single cell to feed the entire world.

“Our vision for the future I’d really love to work towards is instead of having farms outside the city I could see us growing in a facility where we’re locally producing meat inside the city with no need for transportation,” Meatable Chief Technology Officer Daan Luining said in a telephone interview.

Sarah Sorscher, deputy director of regulatory affairs at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, said products like lab-grown meat have “a lot of potential,” but only if they can overcome consumer skepticism.

“Consumers won’t trust them and they will turn on this technology if it’s being forced on them,” Sorscher said, stressing that the industry needs to be transparent about the ingredients and safety of the products. The backlash against genetically modified plants by some consumers offers a cautionary example.

Splitting the regulatory duties might make sense if the FDA assesses risk and approves ingredients at the front end and the USDA handles day-to-day inspections, the Consumer Federation of America’s Gremillion said.

“Right now, one of the things consumers have going for them is protections that are out there will persist,” Gremillion said.

NOT SO FAST

Perdue has said his department and the FDA will aim to produce a joint regulatory plan for lab-grown meat products sometime in the new year.

“If we can get this done in 2019, I think that’d be pretty fast for federal purposes,” he said. Administration officials insist they already have the legislative authority to move quickly on regulatory changes.

But Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.), a senior member of the House Appropriations Committee and long-time champion of creating an independent food safety agency, said lawmakers won’t be stampeded into rubber stamping the administration’s approach.

“More information is needed for Congress to address this emerging sector in the United States and to ensure it is properly overseen by the relevant executive agencies once these products are commercially available,” she said in a statement to Bloomberg Government.

To contact the reporter on this story: Teaganne Finn in Washington, D.C. at tfinn@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Jonathan Nicholson at jnicholson@bgov.com