Super Bowl Chicken Wings May Be Less Likely to Make You Sick

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Football fans can take solace if their team loses Sunday’s Super Bowl: the chicken wings they devour may be less likely to put them at risk of food poisoning.

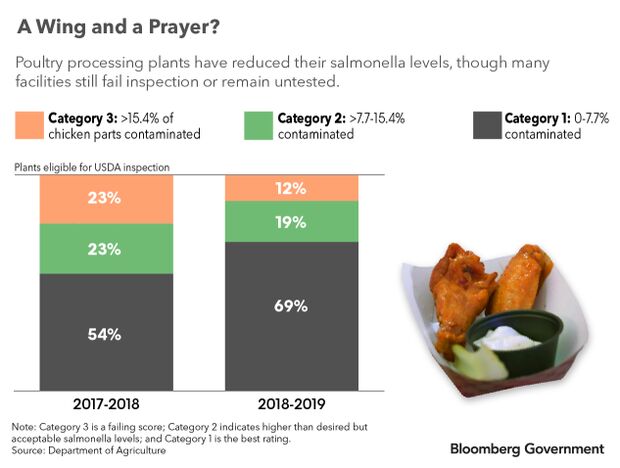

Federal government inspections for salmonella show chicken parts processors making progress in reducing the presence of salmonella, recent data from the Agriculture Department’s Food Safety and Inspection Service suggests. Among plants the FSIS inspected last year, 12% received the worst score for such contamination. By comparison, almost a quarter failed in December 2017-18.

Increased public access to the FSIS rankings has helped create “a strong market incentive for poultry producers to bring their contamination rates down,” said Sarah Sorscher, a deputy director at the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

Americans may consume as many as 1.4 billion wings this weekend—enough to circle the earth three times, according to the National Chicken Council. Among the largest corporations, closely held Perdue Farms Inc. cut its number of worst-scoring plants to two from seven, Pilgrim’s Pride Corp. went to two from six, and Tyson Foods, Inc. plants avoided the worst rating in both years.

“Smaller establishments actually tend to do worse on salmonella performance,” Sorscher said. “They just may not have the same protocols and procedures in place, and the financial capacity to enforce them rigorously.”

Two-dozen smaller chicken operations that the FSIS didn’t test in 2018 failed inspections in 2019. Of those ranked in both years, three fared much worse: Sysco Corp.-owned Buckhead Meat & Seafood of Houston, Texas, Bachoco-owned OK Foods, Inc., in Albertville, Ala., and Gemstone Foods LLC in Florence, Ala.

“Since Buckhead Meat and Seafood of Houston entered Category 3 at the end of December 2019, we have implemented additional actions including more frequent supplier category monitoring and testing of incoming raw material,” Shannon Mutschler, Sysco senior external communications director, said in a statement. “We discontinue working with suppliers that do not implement corrective actions in a timely manner.”

The other two companies didn’t immediately respond to telephone and online requests for comment.

“The industry as a whole (large, medium and small plants) are currently meeting or exceeding the FSIS performance standard for Salmonella,” said Tom Super, National Chicken Council senior vice president of communications, in an email putting the percentage at about 90%.

Salmonella Testing

The FSIS set new standards in 2015 for testing raw chicken legs, breasts, and wings for salmonella. Infection with the bacteria is responsible for “about 1.35 million illnesses, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths” across the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports.

Humans typically contract salmonella by eating food tainted with animal feces. Contamination can occur during an animal’s lifespan or at slaughter. Salmonella is still a risk during food preparation, as cross-contamination and improper storage temperatures spur bacterial growth. Failure to cook raw meat to specific temperatures also can sicken consumers.

Since taking effect in May 2016, the agency’s system determines if manufacturing plants are properly controlling salmonella levels by testing random poultry parts. Whole chickens and ground meats are checked separately, and held to different specifications.

The FSIS rates facilities based on a maximum permissible salmonella presence in 15.4% of chicken parts samples tested over a 52-week moving window. That means salmonella would be present in eight of every 52 chicken parts samples tested.

Category 1 plants “achieved 50% or less of the maximum” salmonella level. Category 2 facilities’ sample results tested higher than 50%, but below the maximum.

Category 3 slaughterhouses showed poultry parts surpassing the maximum level. That triggers a public health risk evaluation, with the possibility of further investigations, a FSIS spokesperson said.

The agency’s rankings are just a “snapshot” because “the number of samples that FSIS takes, compared to 9 billion chickens and turkeys that get killed every year, is relatively small,” said Tony Corbo, a senior lobbyist for Food & Water Watch, an environmental protection advocacy nonprofit. A facility won’t be considered for federal testing if it can’t yield at least 10 chicken part samples, although companies often do their own sampling.

Corbo said the Agriculture Department’s results are “fairly accurate” as a “first brush at establishing standards for parts.” Corbo said the big companies’ use of antimicrobial products on chicken had skewed the ratings for salmonella count in their favor, but the FSIS testing now takes that into account.

“One fear that I have is that the big guys can figure out how to just spray everything down with sanitizers to pass the test,” said Thomas Gremillion, Consumer Federation of America food policy director.

The standards are “relatively lenient” and need to be raised for a more effective federal approach to public health risks, Gremillion said. “The dirty little secret among people that work on food safety in meat and poultry: Prevalence testing for salmonella is a little unreliable,” he said.

Food Giants’ Performance

The biggest companies aren’t relying on the government to safeguard their brands. “The food giants have the capability of hiring their own microbiologists,” Corbo said. “They’re monitoring the levels of pathogens a lot more frequently than FSIS is.”

Tyson Foods reigns as poultry-producing champion, slaughtering more than 235 million pounds of liveweight bird on a weekly basis in 2018, according to WATT PoultryUSA.

The Agriculture Department sampled chicken parts from 37 Tyson facilities in 2018 to test for salmonella – and almost 70% of those plants secured category 1 rankings. None of its establishments fell into the worst tier. One year later, Tyson slaughterhouses improved further, with an additional three facilities rated category 1, bringing the total to around 79%.

The next four biggest chicken producers—Pilgrim’s Pride Corp., Sanderson Farms Inc., Perdue Farms, and Koch Foods Inc.—followed Tyson’s lead, gradually rising in the Agriculture Department rankings since December 2017. Combined, these corporations contributed 406.18 million pounds of liveweight chicken on a weekly basis to dinner tables around the world in 2018.

But in 2019, high rates of salmonella plagued a handful of slaughterhouses belonging to each of the four corporations except Sanderson Farms. In category 3, Pilgrim’s Pride had two facilities, Perdue Farms had two facilities and Koch Foods four.

“Food safety teams at our processing facilities share ideas and technologies across the company and are supported by in house microbiology labs that continually monitor and react to sampling results,” said Jeff Shaw, vice president of quality assurance at Perdue. “While we have made consistent improvement over the last several years, we relentlessly support the need for continuous improvement.”

Officials at the other four top chicken operations didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Battery Acid

Overall, 58% of plants inspected across both years saw no change in their FSIS scores. Of those that did change, that movement was more likely to be for better—32%—compared with about 11% with lower ratings.

Corbo describes the rating system as the “best vehicle” for consumers and grocery stores to gain insight on the poultry they buy – and whom they buy it from.

However, more still needs to be done, he said, citing livestock breeding. “If a flock comes in really loaded with salmonella, they can douse these chickens in battery acid,” Corbo said. “And you’re not going to be able to reduce the levels where they are safe for consumers.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Megan U. Boyanton in Washington at mboyanton@bgov.com; Aaron Kessler in Washington at akessler@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com; Christina Brady at cbrady@bloomberglaw.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.