Subway and Bus Jobs Expose Virus’s Vast, Deadly U.S. Disparity

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

It was shortly after the first of the month, and passengers who had just received public assistance payments packed Antoine Trimuel’s Chicago Transit Authority bus to get to the grocery store.

With capacity on his route cut in half by frequency reductions, he couldn’t get away from people he says were coughing and not wearing masks. On his day off, he went to get tested for coronavirus. Positive. As he feared.

He’s been isolated ever since from his children aged 10 and 3, whom he can only talk to by video chat. His 3-year-old is too young to understand why he can’t see his father.

“I did everything right,” said Trimuel, 40, who’s driven a CTA bus for all of his adult life. “I social distanced from everyone. I wore a mask. I wore gloves. I didn’t touch anything or anybody. But I still came down with this virus. How? I didn’t go anywhere but to work and to home.”

The coronavirus pandemic is exposing the racial and age inequalities embedded in the nation’s bus and subway stops, as transit workers contract the disease in stunning numbers.

In New York City alone, 98 transit workers had died as of May 1: bus drivers, track workers, conductors and station agents. Even as lawmakers and public officials publicly thank transit workers for being there during the pandemic, transit unions in some cities have threatened to walk off the job, saying employers aren’t enforcing policies to keep them safe.

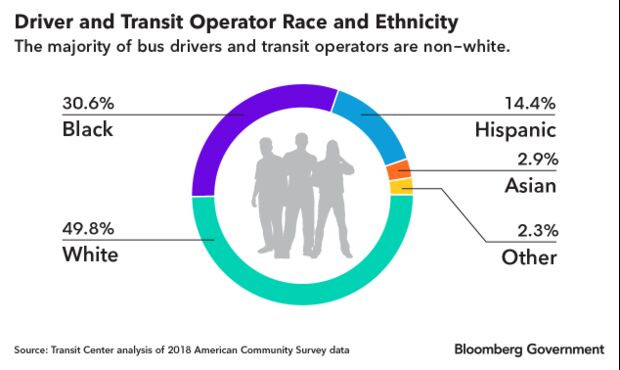

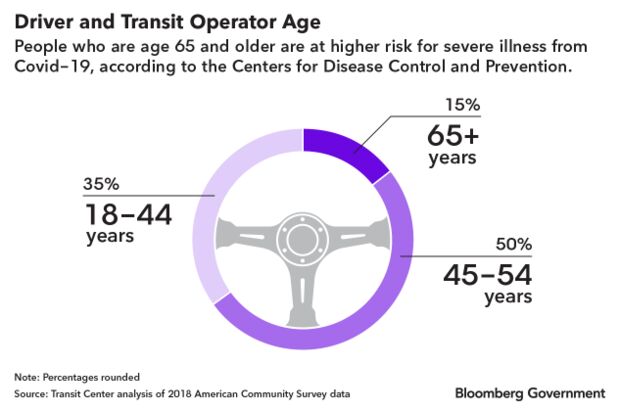

The demographics and responsibilities of transit operators roll up numerous high-risk factors for contracting Covid-19. Just more than half of the nation’s transit operators are people of color, according to U.S. Census data; roughly 30% are black, and 14% are Hispanic. Sixty-five percent are older than 45. Fifteen percent are older than 65.

As essential workers who spend their work days inside enclosed metal tubes, it’s all but impossible for transit operators to completely isolate themselves from the coronavirus, even as ridership numbers collapse and their employers provide masks.

A video of Jason Hargrove, a Detroit bus driver who called out a coughing passenger on social media, has been transformed into a television ad calling attention to the toll the virus is taking on black people across the U.S. Hargrove died 11 days after he recorded the video.

“This is real, you all need to take this seriously,” Hargrove says on-camera.

Already at Risk

Government jobs played an important role in the building of the black middle class in the U.S. It started after World War I, when blacks began migrating from the rural south to urban areas across the country, said Steven Pitts, associate chair of the Center for Labor Research and Education at UC Berkeley.

Those jobs were often more open to blacks than those in the private sector, though black workers were often shuffled into unskilled positions because of their race. Driving a bus was considered a “prestigious job” for black workers, said Gayle Hamilton, interim director of labor at Wayne State University.

“Just moving from the back of the bus to leading the bus, or being in charge of the bus was also a significant powerful symbol in the black community,” Hamilton said.

The retirement age for transit workers is often higher than emergency services professions, such as police or firefighters, said John Samuelsen, president of the Transport Workers Union.

In New York, workers can tap into their pensions once they’ve been on the job for 25 years and are at least 55 years-old, Samuelson said, and that’s one of the best retirement situations in the country.

Samuelson’s union had lost 85 transit workers as of Thursday. Those who died had been on the job an average of 18 years, according to union statistics, though the union only had years of service information for roughly 60 deceased workers.

Black people have also historically dealt with underlying social circumstances that contribute to poor health, such as poverty, inadequate housing, poor education, and lack of access to healthy food, said Clyde Yancy, chief of cardiology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. Coronavirus has pulled back the “curtain” on how these factors affect the black community’s health, Yancy said.

Workers Push Back

In Miami-Dade County in Florida, bus drivers and train operators are suing their employer, alleging that it failed to provide enough protective equipment to safeguard them from the coronavirus. In Philadelphia, transit workers canceled a protest only after their employer agreed to develop a temperature screening program, among other protections. In Virginia, drivers seeking hazard pay called out of work in protest.

Congress gave public transportation agencies $25 billion in its third coronavirus relief package (Public Law 116-136). Agencies are required to submit virus expenses, such as money spent on masks, gloves, and cleaning supplies, to the Federal Transit Administration for reimbursement. As of Friday, the agency had awarded $1 billion, and was processing grant requests for $15 billion, a spokesperson said in a statement.

The FTA has also reached out to encourage transit agencies to coordinate with state emergency operations centers, the offices coordinating state responses to the pandemic, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency to get protective equipment for workers, the agency said in a statement.

The FTA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have also both issued guidelines for transit systems to keep their employees safe, though their advice isn’t enforceable. However, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, under its clause that requires a hazard-free workplace, could cite an employer and reference that guidance, said Rachel Conn, an occupational safety and health attorney at Nixon Peabody LLP. Employees can also file a complaint with OSHA, Conn said.

Transit systems are not reporting having trouble protecting their workers, said Polly Hanson of the American Public Transportation Association, though they did have difficulty finding masks for employees at the beginning of the crisis.

Officials from four of APTA’s 2018 list of top 10 cities by percentage of public transit commuters told Bloomberg Government that they’re also taking precautions beyond providing masks to workers. San Francisco stopped using buses that don’t have a protective barrier around the driver, seats near the bus driver in Chicago are roped off to force social distancing, and Philadelphia is limiting the number of riders per bus, for example.

Transit workers, however, said the protection isn’t enough. Carlos Feliciano, a Chicago bus driver, said he’s been spraying disinfectant on paper and wiping down his bus in the morning because the bus isn’t being cleaned well overnight.

Soon, Trimuel will be rejoining him on the job. After almost a month, Trimuel, who’s spent 19 years in the driver’s seat, says he’s past the terrible cough, chills, and loss of his senses of taste and smell. But he says he won’t get back on the bus until he is symptom free.

In Miami-Dade, Alice Bravo, director of transportation and public works, said in an interview that workers each receive an KN95 mask. The department doesn’t replace the mask after a certain amount of time; instead, drivers are asked to turn them in once they’re worn out to receive a new one. The department’s supplies are scarce, and they don’t want to give drivers a new mask if they don’t need one, she said.

Jeffery Mitchell, president of the Miami transit union suing its employer for failing to protect members, said transit workers aren’t getting enough masks out of the county stockpile. He wonders if any driver is sufficiently protected.

Riders can “transfer onto the big bus and keep the petri dish rolling,” Mitchell said. “How are we telling the public that they’re safe? They’re not.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Courtney Rozen in Washington at crozen@bgov.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.