Student Loan Forgiveness Plan Sputters, Helping 1% of Hopefuls

- Lawmakers look to widen plan to attract public service workers

- DeVos recognizes `substantial confusion’ among borrowers

It was supposed to be a boon for social workers, police officers and charity workers—a federal program that would forgive the student debts of anyone who turned down higher-paying work in the private sector to spend a decade working in the public service or non-profit jobs.

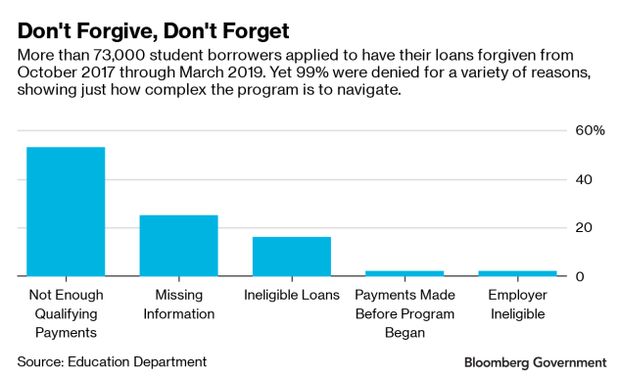

A dozen years later, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, or PSLF, has yet to live up to its promises. Of the 76,000 loan-forgiveness applications processed since October 2017, only 1% were approved by the end of March 2019.

In response, lawmakers and the Education Department are trying to expand the program, provide more information, and work with loan servicers to produce results. Failure to reduce the rejection rate could make it harder for professions such as teaching, firefighting, and the military to attract college graduates, said Betsy Mayotte, president and founder of The Institute of Student Loan Advisors.

“I know people who are in PSLF because of this program and are talking about leaving public service and going into the private sector,” she said, because they don’t feel they’ll ever get loan forgiveness and “can’t afford their loans if they stay” in the public sector. “That’s the whole reason the program was created in the first place.”

Complex Qualifications

On the surface, the program sounded simple: Get a job in the public or nonprofit sector, make 120 payments on your loans, have anything left over forgiven.

The program was never that easy. From the start, 80% of borrowers were disqualified because they had non-qualifying loans—they would need to consolidate their loans in a different program before their first payment would count, a requirement some never learned about until it was too late. They also needed to be in a plan where their payments were based on income, so those in high-paying careers would pay back more.

Narrowing the program’s eligibility partially was done because the program was passed in budget reconciliation (Public Law 110-84) and, under the rules, needed to reduce the amount of money the government spent, said Julie Peller, who worked as an aide at the time for House Education and Labor Committee.

“Frankly, some of this was budgetary,” said Peller, now executive director with Higher Learning Advocates. “We were in a budget reconciliation process and there was a certain amount of pay-fors in the package and a certain amount of savings in the package, and those things had to line up.”

Lawmakers are now trying to expand the program. Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Tim Kaine (D-Va.) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), along with a dozen other Democrats in the House and Senate, introduced legislation (S. 1203, H.R. 2441) that would allow borrowers in all loan and repayment programs to qualify for loan forgiveness, among other changes.

Lawmakers are currently trying to get the bill’s language expanding the loan forgiveness program added to an update to the higher education law (Public Law 110-315) being negotiated.

“We’re expecting to get there,” Kaine said about the plan, while a bipartisan bill has yet to be introduced.

Botched Implementation

For students trying to understand the already complex requirements, a lack of communication from the Education Department and loan servicers didn’t help.

“There was a lot of, ‘Oh we’ll address this in 10 years,’” Peller said. “There was a sense this wasn’t urgent because people won’t be applying until 2017.”

Colleen Campbell was working as a financial aid assistant at the Julliard School when PSLF began and often found herself unable to help students interested in the program.

“I would have students coming to me and saying ‘I’m planning to use PSLF, what do I do, how do I indicate that I’m going to use this program?’ and there was no actual answer until 2011,” when the department released a form allowing students to certify their employer qualified for the program.

Department employees acknowledged that not enough had been done to help borrowers understand the rules.

The department “recognizes there is substantial confusion among borrowers regarding PSLF and intends to implement improvements that will help clarify program eligibility and provide confidence to eligible borrowers that they are on track for forgiveness,” Education Secretary Betsy DeVos recently said in written answers to lawmakers’ questions.

The department launched an online tool to help borrowers understand whether they qualify. Between its launch in December 2018 through June 2019, the tool has been used 216,000 times and helped generate 82,000 forms for both employer certification and applications.

Customer Service?

Most students talk with the companies servicing their loans, not the Education Department. These servicers received fragmented and inadequate guidance from the department on the program, the Government Accountability Office reported in 2018, “raising the risk that the PSLF servicer may improperly approve or deny borrowers’ certification requests and forgiveness applications.”

Servicers also lacked an incentive to help borrowers into PSLF as only one loan servicer—Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency, or PHEAA—handles the loans in the program. As a result, a servicer who helped borrowers get into PSLF would subsequently lose revenue from having fewer borrowers.

“They really did not anticipate that servicers wouldn’t want to lose PSLF accounts,” Campbell said. “Anything that would encourage people to switch to another servicers is not going to fly, and they didn’t do anything to correct for that.”

Officials in the Office of Federal Student Aid said they’re working to ensure loan servicers have the correct information and are sharing it with students. Officials are also reviewing incentives that would encourage servicers to deal with borrowers and exploring how contracts might be updated when they expire in the next few years.

In addition, the department is working to improve the transfer of data between loan servicers and the PHEAA, which hired a consulting firm to help turn non-electronic data into an electric format.

While fixes are coming, loan experts said the 99% rejection rate isn’t as bad as it might appear on first glance.

“There shouldn’t be a ton of people getting forgiveness right now,” Mayotte said, before adding. “But it should be higher than 1%.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Emily Wilkins in Washington at ewilkins@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com