Senators Punt on Finding Long-Term Fix for Highway Trust Funding

- National mileage fee pilot, highway study included in bill

- Amendments show lawmakers’ concerns over fund solvency

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Senators allocated more than $100 billion to bail out the Highway Trust Fund in the bipartisan infrastructure bill, pushing off a pain point for lawmakers that have struggled to find a permanent solution of how to pay for highways and mass transit.

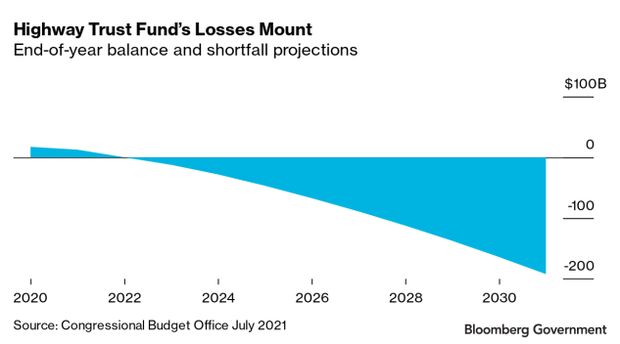

The legislation’s provisions and added amendments could set up Congress to address the fund’s solvency five years from now, senators say. In the meantime, the fund paid out roughly $15 billion more than it took in, just in 2020, with the shortfall projected to grow with each passing year.

The infrastructure bill, which would reauthorize surface transportation programs facing a Sept. 30 deadline, passed in the Senate on a 69-30 vote on Tuesday. It would transfer $90 billion for highways and $28 billion for mass transit to the trust fund to keep it solvent over the next five years.

But the legislation (H.R. 3684) does nothing to change the rate of the gasoline tax—the main source of federal money for highways and transit—which hasn’t increased since 1993. Instead, it creates pilot programs and studies to determine future options.

“I believe there so far have been some missed opportunities, one being reform to the Highway Trust Fund itself,” Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) said on the Senate floor last week. “The current state of the Highway Trust Fund is unsustainable and unless something changes we’re going to be in dire straits—even more dire in just a few years.”

Since about 2008, Congress began spending more out of the trust fund than was going into it. With the gap set to grow ever-larger each year, the fund requires ever-greater infusions of federal funding, exacerbating larger problems with the U.S. deficit, some lawmakers argue. The infrastructure bill overall would add $256 billion to the federal budget deficit over a decade, the Congressional Budget Office said last week.

Senate Passes Boost for Infrastructure in Victory for Biden

Fund That ‘Can’t Trust’

The CBO projected in February that both the highway and transit account balances of the Highway Trust Fund will be exhausted in 2022.

“If the trust fund’s balances were to be exhausted, the federal government would not be able to make payments to states on a timely basis,” Joseph Kile, CBO’s director of microeconomic analysis, said at a Senate committee hearing in April. “As a result, states would face challenges in planning for transportation projects because of uncertainty about the amount or timing of payments from the Treasury.”

Lawmakers adopted amendments to the infrastructure bill that show they want surface transportation programs to be paid for, but haven’t been able to agree on how.

One addition to the bill would require the secretary of the Department of Transportation to study the changes and costs of highway use by different vehicles—the first time a major highway cost allocation study has been done since 1997. The amendment, sponsored by Sens. Cynthia Lummis (R-Wyo.) and Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), had broad bipartisan support with a 95-3 vote.

“We have repeatedly bailed out the Highway Trust Fund,” Lummis said. “That makes it a trust fund that we cannot actually trust.”

Lummis wants the study to tell Congress who is using roadways so that all users, including electric vehicles, fairly contribute to the fund, according to a spokesperson. Kelly said the information from the study would help make decisions to address the Highway Trust Fund’s shortfalls during its next reauthorization cycle, expected in 2026.

Sen. Tom Carper (D-Del.), who led the bill’s floor debate for Democrats, said the study would evaluate the use and damage that different vehicles cause to roads, and compare that to what those users pay to the trust. “It will help Congress ensure that all vehicles pay their fair share,” he said.

Other amendments on funding were introduced, but didn’t make it into the bill. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) also criticized the Highway Trust Fund’s insolvency, and introduced a long-shot substitute amendment that would have transferred unused Covid money to the trust fund, and terminated the fund’s mass transit account entirely. That amendment failed in a 20-78 vote.

User Fees

The Biden administration drew a hard line against increasing taxes on people making less than $400,000, which meant increasing the gas tax wasn’t an option.

“It’s going to require another $118 billion to shore that up because the White House has taken off the table any other pay fors that would include a user fee on electric vehicles or indexing the gas tax, or other ideas that would fill in that gap,” Cornyn said. “I don’t think any of us regard that as a good outcome.”

Some lawmakers have called for a transition to a miles-traveled fee, instead of a gas tax, given the increased push toward electric vehicles. The legislation would spend about $125 million over five years to pilot a national miles-traveled fee and more state mileage tax programs with the goal “to restore and maintain the long-term solvency of the Highway Trust Fund,” the bill said.

Vehicle Mile Tax Draws Fresh Attention as Buttigieg Takes Post

There are already other voluntary state pilot programs for the same issue that were funded from the last surface transportation bill in 2015. Analysts questioned whether the pilots will be able to push lawmakers to force change.

“There’s so little political will to do this; we’ve been doing these studies for many years and I am not convinced that a successful pilot is the only thing standing between us and full implementation of national mileage fee,” said Liisa Ecola, a senior policy analyst at the Rand Corporation who has studied mileage fees. But, she added, “the more we do, the easier it will be to gain the political will to actually make a change.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Lillianna Byington in Washington at lbyington@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com; Bennett Roth at broth@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.