As Seas Rise, U.S. Faces Rising Costs of Island Migration

- Migration due to climate change could cost U.S. and states more

- Citizens of Pacific island nations in pact can move freely to U.S.

The Marshallese are losing their land.

The Marshall Islands, a chain of 29 tiny, low-lying atolls in the Pacific Ocean just two meters above sea level on average, are losing land to the sea twice as fast as the global average in some areas, according to a report by the Government Accountability Office.

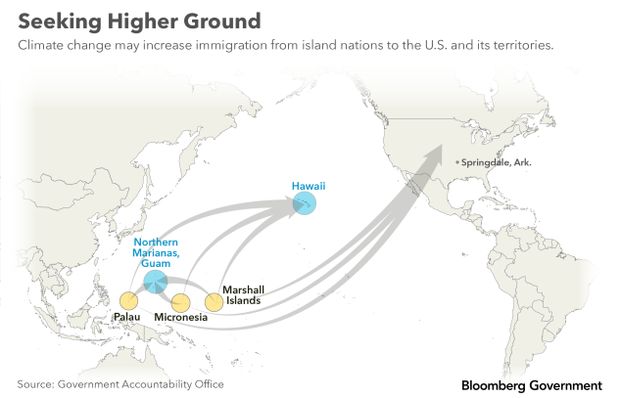

Rising sea levels related to temperature increases aren’t just a challenge for the Marshall Islands, or even other island nations. Some 6,000 miles away in Springdale, Ark., thousands of islanders have put down roots, and more may come. The Marshall Islands is just one of three South Pacific nations that have compacts with the U.S. that easeimmigration rules from islands that aren’t U.S. territories.

Springdale faces funding challenges as more Marshallese in need of education, health care and other services move there. Arkansas officials are trying to learn more about the impact of a growing population of Marshallese migrants in the state.

Because there isn’t up-to-date data on the number of people migrating from the Pacific to Springdale, “they’re underfunded relative to their population,” Randy Capps, director of research for U.S. programs at the Migration Policy Institute, said. “There’s a significant difference, and that means that all city residents, not just the Marshallese, are operating in the weaker infrastructure, weaker funding for services that they would otherwise have. Knowing the size of the population helps assess things like access to health care, insurance rates, utilization rates for local clinics.”

This leaves Congress facing a challenge of its own: how to assess and provide the growing funding needs brought on by increased migration that may be related to climate change.

Several Pacific island nations in particular—those that have Compacts of Free Association with the U.S. that date back to the 1980s—could send even more migrants to the U.S. as conditions deteriorate at home.

Under the compacts, citizens of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federal States of Micronesia, and Palau receive financial assistance and the ability to come and go from the U.S. without a visa. In return, the U.S. has access to these countries’ lands and waters and is responsible for defense and security rights in the countries.

Citizens of compact countries make up about 11 percent of the population in the U.S. territory of Guam, according to a 2019 release by the Department of the Interior. The 2010 census estimated that 4,324 Marshallese people lived in Arkansas, and the number has grown significantly since then, said Sen. John Boozman (R-Ark.).

Boozman sponsored a resolution (S. Con. Res. 3) acknowledging the importance of the Marshallese people to the U.S. and encouraging up-to-date census data on the number of migrants in Arkansas. More accurate data on where these people are and how many of them there are, he says, will help the U.S. better serve them and integrate them into society. The Senate passed the nonbinding resolution, but it hasn’t been taken up in the House.

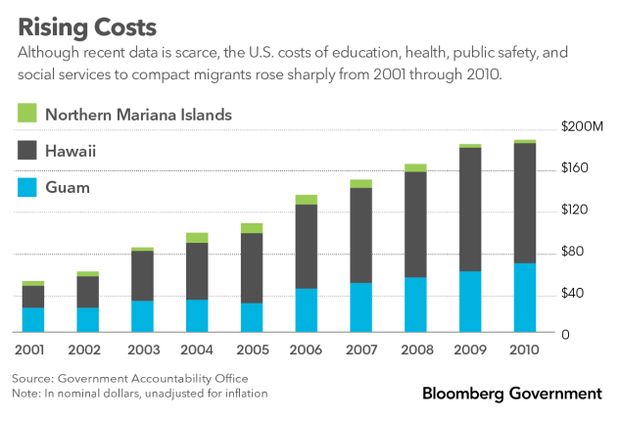

Arkansas state officials claimed around $51 million in costs for education, health and public safety services to compact migrants for 2004 to 2010, according to a GAO report.

“They’ve become a big part of the community,” Boozman said.

Compact Migrants

Residents of theMarshall Islands and other areas affected by rising sea levels and other climate-related issuescould well cause migration influxes into the U.S. that the government is unprepared for.

This isn’t just an island problem. The World Bank Group estimated that 148 million people could be displaced by climate change by 2050—and that’s just within the regions of Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America. Estimates of the number of people who will be displaced by 2050 range from 25 million to 1 billion people, according to a UN environment report.

The State Department, USAID, and the Department of Defense haven’t focused on the link between climate change and migration, according to a 2019 GAO report. The State Department identified migration as a risk of climate change in 2017, but it no longer provides clear guidance to its staff on assessing the risks of climate change, according to the report.

The cost to the federal government could increase with rising numbers of island migrants. As the effects of climate change continue to grow, migration patterns around the world could be affected. Without guidance, according to the report, if may be difficult for the department to identify climate change as a factor in migration.

More than 38,000 compact migrants currently live in Guam, Hawaii, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and American Samoa, according to 2018 census estimates. And more live on the mainland, in states such as Washington, California and Oklahoma. The 2010 census estimated that more than 15,000 people across various mainland states identified themselves as Marshallese. In 2011, the GAO produced a report on the growing migration from compact nations and improvements needed in assessing and addressing that migration.

“Although the compact migrant population represents a tiny fraction of migrants in the United States, the population can have significant impacts on the U.S. communities where they reside,” the report reads.

“They do come here for the long term. Many reside here for the remainder of their lives,” said David Gootnick, director of international affairs and trade at the GAO, in an interview with Bloomberg Government

Increased migration could add to the financial burden of U.S. states. Guam, Hawaii and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands reported more than $1 billion in costs for services for compact migrants from 2001 to 2010, according to a GAO report.

The U.S. under the compact is required to give $30 million per year to four areas deemed to be highly affected by migration from compact nations: Hawaii, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and American Samoa. In fiscal year 2019, Congress also appropriated $4 million in discretionary funds to these areas.

Once the funds were divided, this meant about $16.8 million for Guam, $14.8 million for Hawaii, $2.2 million for the Northern Mariana Islands and a little over $22,000 for American Samoa, according to the Department of the Interior.

The $30 million compact impact funding expires in 2023.

Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-Hawaii) said the current funding isn’t enough to address the migrants’ needs. Hawaii alone spends about $40 million a year just for health care for compact citizens, she said.

“Thirty million shared, split doesn’t go very far,” Hirono said.

People Are Moving

Climate-change related migration is challenging to study because it’s difficult to define a climate migrant, said Erol Yayboke, deputy director and senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in an interview with Bloomberg Government. Climate migrants can’t be classified as refugees under international law.

Though there is much uncertainty, there’s one thing that is certain: people are moving, Yayboke said.

“If you ask someone why they leave home, a lot of times you get the answer, ‘Oh, we’re in search of a better life,’ right? ‘We want a better job, we want to provide for our families,’” Yayboke said.

“And so I think there is an automatic assumption by a lot of people that those people are economic migrants. However, if you peel that onion one layer back, a lot of times people are moving, yes, because they want a better life, but also because there is some sort of shock that happens that’s climate-change related,” Yayboke said.

Decisions Ahead

Congress will have to renegotiate financial aspects of the pacts, which start to expire in 2023, with each island nation. But in the meantime, some residents will have to make their stay-or-leave decisions.

Kitti Kabua, a Marshallese citizen living on the island of Ebeye, feels the impact of climate change looming every day. The Marshallese have a deep connection with their land, and she sees a future where that physical connection is gone. Sea levels are higher than when she was a child, and she can see the difference when the waters are calm and the tide is high. When waves hit the shore, homes on the lagoon side of the island are battered by the water. People want to move inland, she said, but there is “absolutely no room.”

“It’s a daunting thing to think about and more often than not we try to put it in the back of our minds, but it just haunts you into the night,” Kabua said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Elizabeth Elkin in Washington at eelkin@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jodie Morris at jmorris@bgov.com; Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergtax.com