School Shootings’ Rise Fuels Secret Service Training Requests

- Agency helps teachers spot warning signs, intervene in advance

- Lawmakers seek dedicated funding for threat assessment center

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

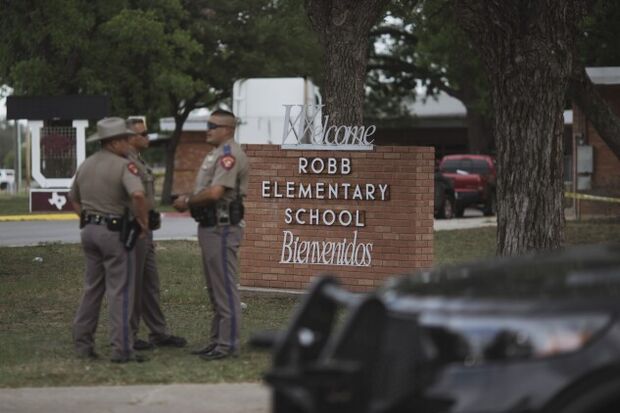

Weeks after an 18-year-old shot and killed 19 children and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, Roosevelt Nivens and hundreds of other educators walked into a school building on the other side of the state determined to learn how to prevent such tragedies.

Nivens, the superintendent of the Houston-area Lamar Consolidated Independent School District, had been invited by an administrator in a neighboring district to a mass-violence prevention session run by the US Secret Service’s National Threat Assessment Center.

For a quarter-century, the agency known primarily for guarding top government officials and rooting out potential threats has been sharing that expertise, dispatching its staff for free training sessions to schools, law enforcement agencies, public officials, and other community members.

Last year was the most violent in what has been an unprecedented surge in shootings at US schools; the more than 250 incidents in 2021 was double the previous year and the highest total on record, according to the K-12 School Shooting Database.

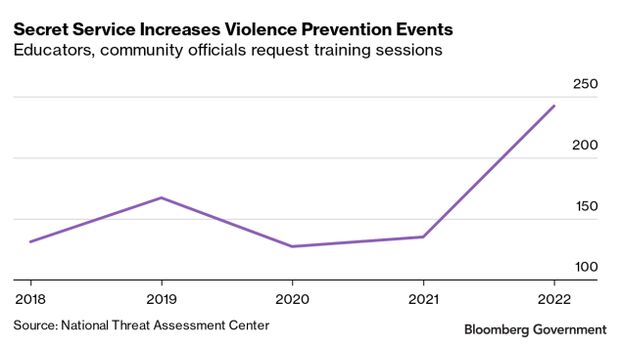

With that has come a spike in calls for help: The Secret Service says its threat assessment center fielded nearly 250 training requests this fiscal year — the most in its history and almost 50% more than its previous high. About half focused on schools, while others dealt with workplaces and other potential targets.

Now, supporters in Congress are pushing for dedicated funding that for the first time since its launch would explicitly fund the center and broaden its reach.

One bipartisan measure would authorize $10 million annually for NTAC and direct it to add staff and plan an expansion. Another proposal would give the center a dedicated $5 million funding stream.

Uvalde Shooting Spurs House Scrutiny of School Security Programs

Lawmakers showed renewed interest in the program after Uvalde, but they’re split on whether to set aside funding the center says it needs. Skeptics are wary of the Secret Service’s role in the school safety space.

Nivens is convinced. He directed every administrator and police officer in his district to attend the July training, which had been planned before the Uvalde shooting.

“Some of that stuff I had never even considered, and I’m in year No. 27 of doing this work,” he said.

His staff is now implementing many of the Secret Service recommendations across the district’s nearly 50 schools.

Proactive Approach

Supporters of the program note how its approach—equipping front-line professionals with the tools to spot and respond to behavioral warning signs from potential shooters—has overtaken what once was the conventional wisdom that all attackers might fit a similar profile.

The proactive threat-assessment strategy is gaining in popularity. New Jersey this year became the latest state to require schools to adopt the approach; Virginia, Kentucky, and others have passed similar laws.

Schools still invest in physical security measures, but they increasingly understand “if you’re relying on those, things are already bad,” said Tom Foley, a security and intelligence professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

In a 2019 analysis of dozens of attacks, NTAC found that most schools where attacks happened had physical security measures in place, such as cameras and lockdown protocols. But they lacked threat assessment and intervention procedures or systems for students and community members to report concerns.

Last year, the center studied 67 disrupted plots and concluded nearly all were stopped because administrators, public safety professionals, or bystanders identified visible warning signs and took steps to intervene.

“We almost get re-traumatized every time we see these cases because we see it in the research,” NTAC Chief Lina Alathari said. “We just want to make sure that the Secret Service is getting out there in the community and teaching people.”

Secret Service’s Own Secrets Come Under Scrutiny in Jan. 6 Probe

The violence prevention work has drawn plaudits within the education and public safety communities—a welcome bright spot for an agency beset by high-profile missteps in other areas, including recent controversy over missing records related to the Jan. 6 attack on the US Capitol.

Post-Columbine Push

The Secret Service’s work on school safety is both a natural extension of its core mission and a response to one of the most notorious school shootings in US history.

The agency was formed in 1865 to combat financial crimes and eventually took on what’s now its signature role within the Department of Homeland Security: protecting the president and other top government officials. The Secret Service created the assessment center in 1998 to add academic heft to its methods for sizing up potential threats, and to share those lessons with state and local law enforcement agencies.

After the Columbine High School massacre in 1999, NTAC also began analyzing the uptick in school violence, and partnered with the Department of Education to research attacks and prevention methods, using interviews, public records, and case files from law enforcement agencies.

NTAC’s team of 30 interdisciplinary researchers has since issued a half-dozen reports on identifying and preventing school attacks. It has also conducted more than 1,200 training sessions for more than 120,000 participants in the past decade alone.

Among its tools is a list of 11 key questions school officials and others can use to understand whether a student of concern poses an actual threat—including whether they have the capacity to carry out an attack, whether they’re experiencing despair, and whether they have a trusting relationship with any responsible adults.

Foundational Research

The Secret Service’s work, including the 11 questions, “have really guided our approach to threat assessment and shaped the whole field,” said Beverly Kingston, director of the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence at the University of Colorado.

University of Virginia professor Dewey Cornell said he uses the Secret Service research to inform his own threat-assessment model, which is required in around 4,000 K-12 schools in Florida and has been taught in thousands of others across the US and Canada.

The questions are also integrated into a risk-assessment training used in Missouri schools, which by one count have had two dozen shootings and gun incidents in the past 20 years.

“What we like about their research and those 11 questions is that it considers the context of what’s going on,” said Amy Roderick, director of the Center for Education Safety at the Missouri School Boards’ Association. “It’s not so narrow or tunnel-visioned into a single incident.”

Roderick also said she liked how the trainers at NTAC sessions invited school officials on stage to analyze hypothetical red flags and practice the threat assessment model.

Researchers also teach school officials to establish reporting systems, such as online forms or apps, for bystanders to raise concerns.

The Secret Service doesn’t have data on whether attacks have occurred at schools that participated in training sessions but is developing metrics to evaluate the program’s success.

Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul (D) has helped organize seven such trainings with nearly 2,000 participants since 2020. He said they’ve been effective, but declined to discuss specific averted attacks.

One of his staff members was a survivor of the July 4 parade shooting in Highland Park, Ill., where a 21-year-old killed seven people and wounded dozens more.

Raoul said the killings underscored for him the importance of identifying potential threats. “These acts of targeted violence tend to occur over the course of just a couple of minutes, if not seconds,” he said.

Some safety professionals are more skeptical about the Secret Service’s role in school-violence prevention, arguing that the space is getting crowded.

School officials are “bombarded” with information from vendors, consultants, and agencies on how to keep students safe, said Ken Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services, a firm that provides training to schools for a fee.

“At what point do they start drowning one another out?” said Trump, who has no relation to the former president.

Adopting proactive measures also isn’t a guarantee of safety; threat-assessment policies in Uvalde weren’t enough to identify or stop the deadly attack.

Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), who oversees homeland security appropriations in the Senate, said the Secret Service does good work on violence prevention but that he was skeptical of school safety initiatives led by law enforcement agencies, which by their nature are “not in the business of educating and building healthy kids.”

Getting training directly from the federal researchers who’ve led threat assessments for decades has unique value, NTAC Assistant Chief Steven Driscoll said. “This is something that the Secret Service lives and breathes ourselves,” he added.

Jeff Pierson, executive director of the Department of School Safety in Jefferson County, Colo.—which is home to Columbine High School—credited the Secret Service with having a bird’s-eye view of targeted attacks across the country.

“They have the oversight, I think, of so much that maybe we don’t see,” said Pierson.

Congressional Action

One bipartisan proposal (S. 391; H.R. 1229) championed by Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Rep. Ted Deutch (D-Fla.) after the 2018 Parkland, Fla. attack, would authorize $10 million annually for NTAC and direct it to expand its staff, research, and nationwide training. The proposal hasn’t advanced, sidelined amid broader debates over school safety and gun restrictions.

House Passes Bipartisan Gun-Safety Bill, Sending It to Biden

Other lawmakers are trying to bolster NTAC through the annual appropriations process. House Democrats proposed $5 million for NTAC in fiscal 2023. It’s a minuscule sum in federal budget dollars but a significant first step in dedicated funding for the center, which currently competes for money in the Secret Service’s broader operations allocation.

The Secret Service was unable to provide past budget breakdowns specifically for center, but former Director James Murray in May said $4.5 million in funding for NTAC would allow it to maintain current levels of training.

“This is huge for them, if we pass it,” said Rep. Dutch Ruppersberger (D-Md.), who pushed for the House provision. “Their mission is more important now than ever.”

Senate appropriators, led by Murphy, didn’t include specific language on NTAC in their own bill for fiscal 2023 but did propose a $97 million boost for the Secret Service’s overall operations budget—a 4% increase. Final decisions on the Secret Service’s budget for fiscal 2023 are months away, when lawmakers are expected to work on an omnibus spending bill.

Raoul, the Illinois attorney general, is hopeful lawmakers see boosting the program as a no-brainer.

“This is something people on both ends of the political continuum can and should support,” he said. “This should be nothing controversial.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Ellen M. Gilmer in Washington at egilmer@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John P. Martin at jmartin@bloombergindustry.com; Sarah Babbage at sbabbage@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.