School Lunch Shaming on Congress Plate for Child Nutrition Bill

- Students who accrue meal debt face no meals, different fare

- ‘Honest forgetfulness’ may mean cheese sandwich and water

Brandi Whited’s 6-year-old daughter told her mother she was hungry when Whited picked her up from kindergarten in early 2018. Her lunch had consisted of only a cheese sandwich and water.

The reason? Over the Christmas holiday, Whited had overlooked a notice from the school district saying she owed a “couple of dollars” in student lunch debt. By the time students returned to school, the debt had risen to the $12.50 limit allowed before students are served alternative meals. She said her daughter still hasn’t forgotten.

“She felt like she’d done something wrong and if you bring it up, she’ll tell you she thought she was being punished,” said Whited, who lives in LaGrange, Ga. Her daughter ate cheese sandwiches for several days before Whited was again notified of the debt, Whited said.

Whited’s experience – and that of her daughter, who Whited asked not be named – may become less common as a bipartisan group of lawmakers want to take on “lunch shaming” as part of a rewrite of the federal school nutrition law this year. “Lunch shaming,” according to critics, is where students unable to pay for a school lunch are denied food, given alternate meals or otherwise stigmatized in order to get their parents to pay up.

“There’s no excuse today for a child to be embarrassed,” Rep. Glenn Thompson (R-Pa.), a member of the House Education Committee, said in an interview. “The debt needs to be looked at.”

‘Shouldn’t Be Happening’

The issue has taken on a higher profile in recent years as school districts, already strapped for cash, have seen unpaid balances rise, leaving them with a choice between pushing harder to get paid or cut spending elsewhere. New Mexico and Virginia passed bills prohibiting schools from shaming students who have fallen behind on their lunch debt. Several other states have also seen legislation introduced.

Senate Agriculture Chairman Pat Roberts (R-Kan.) said he would consider legislation on the issue if it were reintroduced. With the major farm law (Public Law 115-334) enacted last year, the committee will likely have more time to focus on the Child Nutrition Act, which hasn’t been reauthorized in almost 10 years. “It’s a problem and we’ll take a look at that,” Roberts said.

Roberts’s Democratic counterpart on the committee, ranking member Sen. Debbie Stabenow (Mich.), said lunch shaming merited legislative attention. “That is certainly something that shouldn’t be happening,” she said in an interview earlier this month. The Agriculture Committee has jurisdiction over the Child Nutrition Act in the Senate, while in the House the measure comes before the Education & Labor Committee.

‘Honest Forgetfulness’

Schools participating in the National School Lunch Program, administered through the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service, provide meals subsidized by the federal government. Meals for students eligible for free or reduced price lunches get the most reimbursement from the government, while those for students who pay full price get the least.

Students who forget their lunch money or can’t afford it have the meals charged to their account and if it isn’t paid back by the end of the school year, it falls on the school districts to offset the costs. The National School Lunch Program allots no money to make up the debt.

While a group representing school lunch administrators and workers, the School Nutrition Association, supports federal efforts to combat lunch shaming, Diane Pratt-Heavner, SNA’s director of media relations, said “in terms of specific language, we’d have to take a look at that.”

Seventy-five percent of school districts across the country reported unpaid school meal debt, according to a 2018 SNA survey of more than 1,200 districts. The debt per district ranges from $10 to $856,000. The median district debt – exactly in the middle of the distribution – was $2,500 in 2018, up 25 percent from $2,000 in surveys in 2016 and 2014.

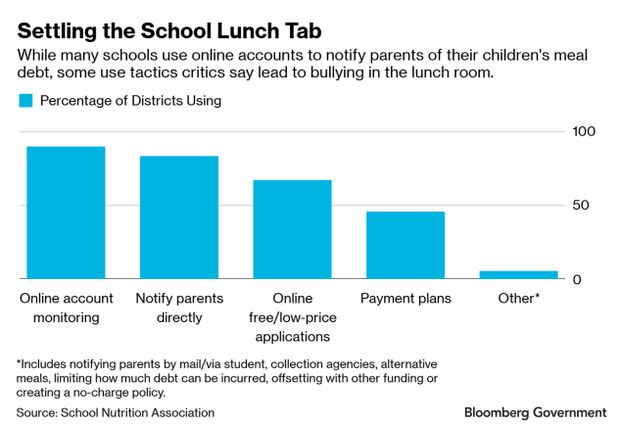

To get parents to pay, schools use various methods. Tactics used most often include online payments, school staff notifying parents directly, and offering assistance to families for completing the free and reduced price meal forms, according to the 2018 SNA survey. A small percentage – less than 6 percent – of the districts surveyed reported using tactics critics say are the most shaming, such as offering different meals to the students or employing collection agencies.

While the district has provided online payment options and low balance letters, Whited said, with some parents it’s just “honest forgetfulness” when they rack up debt. Her children do not qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

Prohibition on Identifying

Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.)will be introducing an anti-lunch shaming bill in the coming weeks, according to an aide.

In 2017, Udall introduced the Anti-Lunch Shaming Act (S. 1064) that would have required any communication related to outstanding credit be directed to the child’s parent or guardian. It would also have blocked schools from publicly identifying a child who doesn’t have funds for a meal or has outstanding credit, such as requiring a wristband or hand stamp.

An identical bill (H.R. 2401)was introduced in the House in the previous Congress and co-sponsored by 147 bipartisan lawmakers in the last Congress. Reps. Rodney Davis (R-Ill.) and Deb Haaland (D-N.M.) will reintroduce the bill this Congress, according to a spokeswoman for Davis.

Currently, there is no federal policy for districts on handling meal charges. The USDA’s FNS leaves it to the state and school food authorities to develop a policy, though it has discouraged school districts from using “hand stamps, stickers, or other visual markers to identify children with lunch debt,” according to an FNS release.

Food Versus Debt

While well-intentioned, the anti-shaming bills could actually make the unpaid debt problem worse for school districts, according to one school lunch administrator.

Legislation that would make it so children could receive meals even if they forgot their money or have debt could only increase the debt and deter families from paying for lunch, according to Jodi Risse, supervisor of Food and Nutrition Service at Anne Arundel County Public Schools in Maryland.

“The way to get a free meal is if you qualify for it,” said Risse. Anne Arundel has 84,000 students with $25,000 in total school meal debt. The school has a $15 limit of debt per student.

Whited said her son, who was in sixth grade at the time of the incident with her daughter, now skips lunch altogether if he forgets his lunch money.

“He’s seen kids getting that kind of lunch and he’s old enough to get made fun of if it happens” said Whited. “He has a fear about that.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Teaganne Finn in Washington, D.C. at tfinn@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Jonathan Nicholson at jnicholson@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com