Safety Net Sought for Students in Limbo After School Closures

- Students stranded without degrees, saddled with debt

- Education Department crafting rules on teach-out plans

At first, she thought it was a joke.

Anita Trevino, a mother of two working full time as a phlebotomist, was five months away from getting her associate’s degree at Brightwood College in Salida, Calif. She’d racked up $44,000 in debt, but was sure it would be worth it when the degree helped her get a better-paying job.

Then she got an email in early December that her school—and all schools owned by Education Corporation America—would permanently close in two days. The same email was sent to about 19,000 other students attending schools in the for-profit chain.

Under the law, schools on the brink of closing are required to come up with plans spelling out what will happen to students in the event of a shutdown. That didn’t happen in the case of ECA schools. Similar stories played out in recent years when Corinthian College and ITT abruptly closed their campuses.

Transferring would leave Trevino far behind and mired in federal and private loan debt as none of the schools she has contacted would take more than her general credits.

“It’s unfair,” she said. “I put the work in, I know what I know. Starting over—it’s so hard. I can’t imagine doing it all over to myself and my kids.”

‘More Schools Will Close’

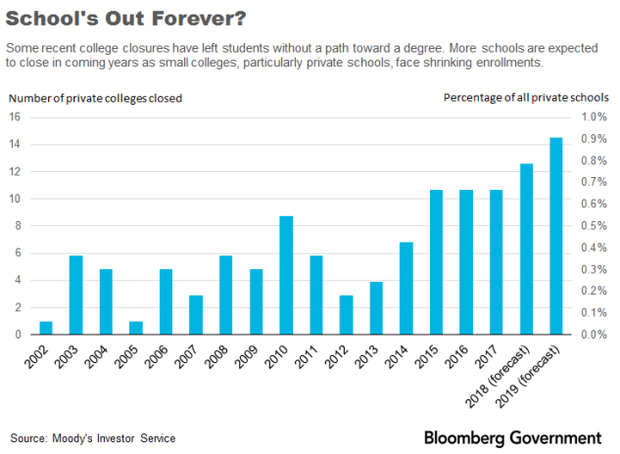

Stories like Trevino’s could become more common as small public and private nonprofit colleges face declining enrollments and for-profit schools deal with battered reputations.

“More schools will close,” said Diane Auer Jones, principal deputy undersecretary at the Education Department, said at a conference last month. “We want to figure out how you wind down a school productively, safely and responsibly.”

Department officials have proposed allowing struggling schools to keep receiving federal financial aid, also known as Title IV money, for up to four months while they work with other schools to take on their students, known as teach-out agreements.

There also are deeper structural issues with regulations that can lead to to colleges, and their accrediting agencies, waiting until the last minute to seek help, said Clare McCann, deputy director for federal higher education policy with New America, a think-tank.

“What you see with schools like ECA or Corinthian or ITT is the accreditors too often don’t get a teach-out agreement early in the game,” McCann said. “If you waited to the point where you lost accreditation, it’s too late.”

Risk of Closure

In an ideal situation, a college facing a potential closure would find schools where students could finish their programs. The three bodies that oversee colleges—accrediting agencies, states, and the Education Department—have roles in ensuring a smooth transition.

Yet, it can be difficult for schools to admit they need to start considering backup plans, said Antoinette Flores, an associate director for Postsecondary Education at Center for American Progress, a liberal advocacy group.

“When a school is at risk of closure and trying to come up with some kind of deal to stay open, it’s not at the top of their list to figure out where the students will go because they’re trying to keep the institution open,” she said.

If a school doesn’t initiate a plan for students, federal regulations put responsibility on the accrediting agency to ask for a plan.

However, the law doesn’t ask for much. Accrediting agencies don’t need to request a plan for students until schools are in dire need, often facing losing federal funding.

The statute requires accreditors to ask for a plan, rather than a more detailed agreement that is needed between the closing school and other institutions for the teach-out to happen.

Because an agreement requires a struggling school to admit its problems to competing institutions, some accreditors hesitate to ask for anything more than a plan, McCann said.

“If you publicize the closures, there’s a reputational component there,” McCann said. “An accreditor is protecting that institution from risk by requiring the teach-out plans rather than the agreement,” she said.

There also are few punishments for accreditors and colleges that leave students hanging after a school shutdown, said Matthew Bruckner, a professor who studies higher education and bankruptcy at Howard University Law School.

“There’s not a lot of penalties involved for not putting together a teach-out,” Bruckner said. “There’s a lot of expectation of good faith.”

Continued Aid

Mitchell Fuerst, president of Success Education Colleges, has successfully helped teach-out students from eight other schools. Things often go wrong when the school is barred from federal student aid, he said.

“The minute they cut off Title IV, that cuts of the lifeline of the institution,” Furst said. “They will have a precipitous closure.”

The department made several proposals in draft regulation to continue support for struggling schools, including allowing closing schools to receive financial aid for up to four months and remain accredited long enough to put a teach-out in place.

The department also proposed clarifying that teach-out plans can happen before a school closes and that they must identify other programs where students could be sent.

“We need to redefine what a teach-out is and do it in such a way that allows a school to raise its hand earlier and say, ‘We’re having some financial challenges here,’” Jones said last month in an interview with Bloomberg Government.

‘They Just Took’

Whether the department’s proposals will make it into the final regulation remains to be seen. While it would provide more time for schools to prepare for a teach-out, finishing a degree at a troubled school might not be the best option for students who can get their federal loans forgiven and start over at a more credible school.

“Is it helpful for students to spend their time at what otherwise would have been an unaccredited school?” Bruckner said. “That’s not clearly helpful for students.”

Trevino isn’t sure whether or not she’ll get her associate’s degree—she hasn’t heard anything from ECA since the email informing her the school would close. Forgiveness of her federal loans could take as long as three years, and her private loans wouldn’t be covered. She joined about 200 other students in suing the school, but there are things besides money she won’t be able to get back.

“I’ve been robbed of my time, of my person, of my motherhood,” she said, “They just took. They just closed the door on me.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Emily Wilkins in Washington at ewilkins@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com; Jonathan Nicholson at jnicholson@bgov.com