Rushed Redistricting Lawsuits Yield Less ‘Dirt’ for Map Critics

- Discovery process can strengthen gerrymander claims

- Short timelines help officials assign voters to districts

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

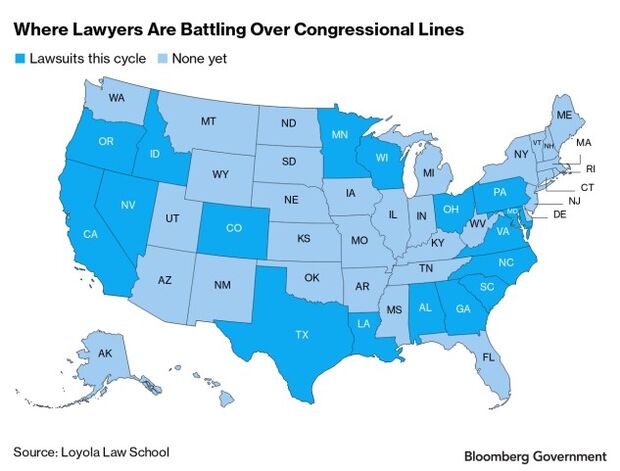

State courts have been speeding redistricting cases to rapid conclusions, frustrating lawyers who want as much time as possible to dig up evidence of illegal gerrymandering.

In two Ohio cases, challengers to a new congressional map giving Republicans a 13-2 advantage were given just a week to gather information. They couldn’t depose key players, were unable to pierce attorney-client privilege around the work of GOP consultants, and had to present their case to the Ohio Supreme Court within a month.

“To go from filing to fully-briefed in less than a month is pretty extraordinary,” said Julie Ebenstein, senior staff attorney for voting rights at the American Civil Liberties Union. “By definition we’re going to have limited opportunity to obtain evidence.”

( SUBSCRIBE to the Ballots & Boundaries newsletter to follow how states revise political districts.)

Those limitations were a byproduct of courts trying to balance competing priorities. States need to set filing schedules, election dates, and make sure that only valid votes are counted in state and congressional primaries, some of which can’t be done until district lines are settled. At the same time, questions about the fairness of the lines must be resolved before confirming boundaries that will influence the makeup of Congress for a decade.

Adding to the time pressure is the pandemic-caused delay at the U.S. Census Bureau that slowed the release of essential population data.

The end result puts challengers at a disadvantage, said Adam Podowitz-Thomas, senior legal strategist at Princeton University’s Electoral Innovation Lab.

Some challengers could be left having to rely on mathematical formulas to back up their claims of partisan bias. Judges tend to give legislators the benefit of the doubt, so “if a litigant doesn’t have the time to develop discovery to prove the map wasn’t drawn in good faith, it makes it harder to overcome that natural bias of a judge,” he said.

Mark Gaber, senior director of redistricting at the Campaign Legal Center, has had clients on the losing end of two speedy state supreme court rulings this cycle. The Colorado Supreme Court received Gaber’s petition challenging Hispanic representation in the state commission’s congressional map on Oct. 7, and without providing for evidence-gathering, the court approved the map 25 days later.

In November, the Wisconsin Supreme Court hamstrung a suit Gaber helped bring on behalf of voting rights activist groups. The justices ruled they wouldn’t hear partisan gerrymandering arguments, that maps should make the least changes possible, and the lawyers would have 20 days to get evidence.

Evidence Found

In contrast, in the last redistricting cycle years-long litigation dug up details that helped score victories for map challengers.

For example, a federal court found an unconstitutional gerrymander in Wisconsin when Republicans drew maps with names like “aggressive” to note plans giving the GOP a better edge; and a federal court ruled Ohio’s congressional map was unconstitutional when litigation dug up evidence that Republicans intentionally drew a “sinkhole” to weaken Democratic power and pack voters into what drafters termed “dog meat” territory in Ohio’s largest city, Columbus.

But those victories were short-lived.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Wisconsin challengers didn’t have standing to sue, and in 2019 the justices held that partisan gerrymandering claims couldn’t be brought in federal court at all. Now, due to time pressure, state courts are limiting his ability to get evidence too, Gaber said.

“You often find lots of really important evidence in discovery that you don’t know exists prior to seeking it,” he said. “So we’ll lose a bit of that sight into the process which can shed important light into the intent of legislators.”

Preliminary Injunction

So far this cycle, North Carolina has been an exception to the trend.

There, the state Supreme Court issued a preliminary injunction and delayed filing deadlines, preventing the state from moving forward with elections while cases contesting the congressional district lines move through evidence-gathering and argument phases.

But even that case is moving quickly. A three-judge panel held a hearing on the maps this week in Raleigh because much work has to be done to prepare for elections. That includes a months-long process in which secretaries of state update qualified voter files.

In Maryland, Robert Popper, senior attorney for the group Judicial Watch, said his team was in a hurry to file its partisan gerrymandering suit in state court before Christmas.

If they can’t quickly block the map, which Democrats passed over Gov. Larry Hogan’s (R) veto, Judicial Watch will push for “full discovery,” Popper said. “We will talk to everyone, and I mean everyone.”

The end result of all the hurrying, Podowitz-Thomas said, could be both less dirt-digging and some upheaval if elections take place under district lines later found to be invalid.

“We’re going to have a lot of cases where the courts are rushing the process that just don’t get resolved in time,” Podowitz-Thomas said. “We just don’t have time.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Ebert in Columbus, Ohio at aebert@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Katherine Rizzo at krizzo@bgov.com; Tina May at tmay@bloomberglaw.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.