Rail Prevails as Long Trains Block First Responders at Crossings

- States, localities losing court fights to ticket trains that block intersections

- Industry, administration don’t want one-size-fits-all federal rules

The call came in: a person was threatening suicide just 2 1/2 blocks from the police department building in Davis, Okla.

It should have taken officers in the town of 2,800 about one minute to get there. It took closer to 20. Three rail crossings stood between the department and the caller; all three were blocked by a stopped freight train.

The officers made it in time, but the memory sticks with Davis Chief of Police Dan Cooper.

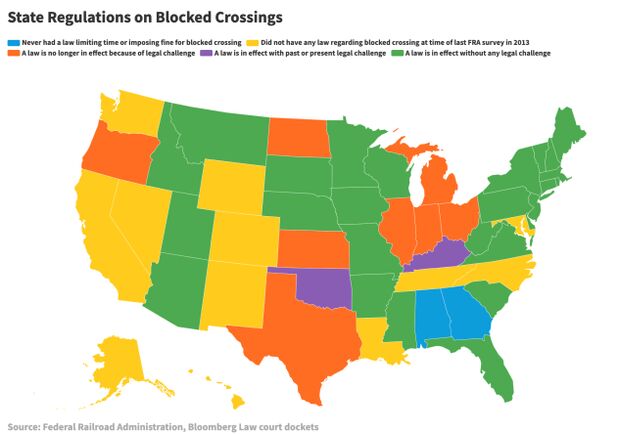

Thanks to a new Oklahoma law that prohibits blocking a crossing for more than 10 minutes, Cooper and his officers can now issue tickets to freight trains—and they have, three times as of mid-August. Frustration over blocked crossings has united state and local officials across party lines as trains grow longer; 38 states had some kind of law on delays when the Federal Railroad Administration last counted in 2013.

But state and federal courts have consistently knocked down the statutes in recent years, and there’s no federal standard for train length or how long a stopped train can block crossings. The FRA doesn’t even define a blocked crossing, and the powerful railroad industry association—which spent $13 million on lobbying over the first two quarters of 2019—is working to make sure it stays that way.

“The rail industry says it’s a state issue, but states aren’t allowed to do anything,” said Dan Lipinski (D-Ill.), chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee’s Subcommittee on Railroads, Pipelines and Hazardous Materials. He said he may draft legislation or legislative language to address blocked crossings.

“We don’t want to choke off the rail industry, but at the same time I think it’s important that we maintain safety,” he said.

Industry Changes

Freight train length has increased in recent years, all seven Class I freight railroads told the Government Accountability Office, according to a July report to Congress. Two of the seven reported their average train lengths had grown 25 percent since 2008, with some trains stretching as long as three miles.

The longer trains lead to crossings being blocked more often and for longer periods, state and local officials told the GAO, citing anecdotes of children in Ohio and Texas crawling through stalled trains to get to school.

The difference is in the length of cars, not their number—reflecting changes in the types of freight carried. The median train shrunk by two freight cars between the first quarter of 2010 and the first quarter of 2019, according to the Association of American Railroads, the industry’s lobbying arm, which measured the length of about 8 million trains.

A train of 150 cars—the FRA’s unofficial definition of a long train—carrying iron ore would run about 3,500 feet long, but an intermodal train of the same number of cars might measure 33,000 feet, according to John Gray, the AAR’s senior vice president of policy and economics.

“Today the growth business for the railroads is taking trucks off the highway. It’s in the intermodal business,” said Gray, who said he sees no way around blocking crossings. “The number of actual freight cars hasn’t changed materially, but you have a change in the length of the freight cars being used just because business has changed during that time.”

Cooper would like the railroads to build a new siding so longer trains can pull off and not block Davis’s crossings.

“We’re just wanting to be a good neighbor with the railroads and hoping that they do too. Especially for the smaller communities where it’s vital that we get our first responders out and about,” he said.

For an interactive version of the map above, click here.

Congressional Action?

The FRA has taken a voluntary approach to blocked crossings. Federal Rail Administrator Ron Batory recently sent letters to the leaders of more than 160 railroads asking them to consider avoiding blockages at crossings, according to an email from an FRA spokesperson.

“In cases where blocked crossings are widespread or recurring, FRA regional personnel have sought to facilitate good-faith negotiations between local officials and railroads to identify potential solutions,” the spokesperson said.

House Transportation and Infrastructure Chairman Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) challenged Batory on the agency’s approach during a July hearing. Oregon saw its state law knocked down in 2009.

“I have trains now running up the Willamette Valley that are 15,000 feet long, going through city centers,” DeFazio said. “How long do we going to allow people to block emergency vehicles? These are mostly at grade crossings. Is there any limit to how long they can make these trains?”

Batory said federal law doesn’t allow the agency to regulate crossing blockages. When pressed by Republican subcommittee member Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.) on whether it should, Batory said, “I’m not a big believer in silver bullets that correct it for everything across the country. I would say no.”

Bipartisan Reluctance

The reserved federal response isn’t new to the Trump administration, though lengthening trains are making the issue more painful for some localities.

President Barack Obama’s FRA administrators, Joe Szabo and Sarah Feinberg, both told Congress they work with railroads and localities to address blocked crossings at the local level, and neither openly embraced offers from lawmakers to give the agency new authority.

The FRA’s positions are that there is no empirical basis to create a one-size-fits-all restriction on the length of a train, and that regulations to prohibit blocked crossings would be unenforceable given how many exceptions exist for other federal rail-safety rules. It has put out a notice of information collection and a request for comment on how and whether the administration could improve data collection on instances of blocked crossings—work that began as a proposal under Feinberg.

The AAR’s Gray notes there is no data on the size or scope of this issue and questioned how anyone could legislate or regulate without such information.

“We will not support any effort to mandate operational decisions that is not supported by sound data and advances public safety,” Jessica Kahanek, a spokeswoman for the rail lobby group, said in an email.

The AAR has long been a quietly powerful force on Capitol Hill. “The state of railroad lobbying is strong. They’re not one of the biggest industries in terms of lobbying spending, but they are still spending millions of dollars on their effort and they have been for years,” Dan Auble, a senior researcher for the Center for Responsive Politics, said.

Lipinski says the solution has to come from Congress. His provision could find its way into the House version of the surface transportation bill the committee is working on before the Sept. 30, 2020 deadline.

States Strike Out

Since the 2013 FRA tally, 10 states have faced or are facing legal challenges to their laws on crossing blockages, resulting in eight repealing their laws or having them knocked down. Two other states are in litigation.

Freight railroad CSX Corp. sued the city of Defiance, Ohio, in September 2016 over $35,000 in fines levied for violating a state law that prohibited blocking crossings for more than five minutes. Judge James Carr of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio in April 2017 found in favor of CSX that federal law preempts state law over railroads.

Railroads, in some cases in conjunction with the AAR, have also successfully sued seven other states: Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, North Dakota, Oregon and Texas. The state laws, some with fines of just $100, no longer apply.

The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Council on Rail is meeting this month to address blocked crossings and long trains, among other topics. “We’re all sitting around saying that we have the same problems,” said the council’s vice chairman, Matt Dietrich, executive director of the Ohio Rail Development Commission.

The AAR in 2018 sued the Kentucky attorney general and leaders of two counties in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky on behalf of Norfolk Southern Corp. , after law enforcement in the counties issued citations against the railroad for blocking crossings. Under Kentucky law, stopped trains that block crossings for five or more minutes can be fined between $25 and $100 for each offense.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt (R) signed into law May 29 an emergency bill prohibiting a railcar from stopping and blocking vehicular traffic at a railroad intersection with a public highway or street for longer than 10 minutes. The law took effect July 1 and two towns, Davis and Edmond, used the new authority to issue several $1,000 tickets.

Cooper, the Davis police chief, said he’s concerned he may not have that power for long.

“I figure before this is over said and done that we will end up in federal court over it,” he said Aug. 12.

He was right. BNSF Railway Co. filed suit on Aug. 22 in the United States District Court for the Western District Of Oklahoma against the Oklahoma Corporation Commission and the cities of Edmond and Davis.

To contact the reporter on this story: Shaun Courtney in Washington at scourtney@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com