Public Colleges Woo Wealthier Students With Aid They Don’t Need

- Need-based assistance grows more slowly than merit, other aid

- Competition for top students raises concern over who gets help

Three years ago, Jeffrey Hecker noticed many of Maine’s top high schoolers were attending private colleges or leaving the state. They had been enticed in part by hefty financial aid packages that allowed them to pay less than they would at their own flagship school—the University of Maine—where Hecker was provost.

So, the university began offering top students bigger scholarships. And because Maine’s population is older than average, the university offered another deal to attract out-of-state students: anyone meeting certain academic criteria could attend for the same tuition charged by the flagship university back home.

The end result is that the university, like other taxpayer-supported public colleges across the country, is dedicating an increasing portion of funds to non-need-based aid—money that otherwise might go to students with genuine financial need.

“There might be cases to award someone for talent of some kind, but it’s way beyond that,” said Stephen Burd, a senior policy analyst with the Education Policy Program at New America, a Washington think tank. “All of the incentives that are in the current system push toward recruiting wealthier students.”

National Trend

At the University of Maine, non-need-based aid increased sixfold, to $12 million in the 2017-2018 school year from $2 million in 2012-2013. The number of students receiving aid despite being judged to have no financial need rose over the same five years to more than 21% of the school’s population from less than 5%, and the average scholarship amount increased as well.

The trend is national.

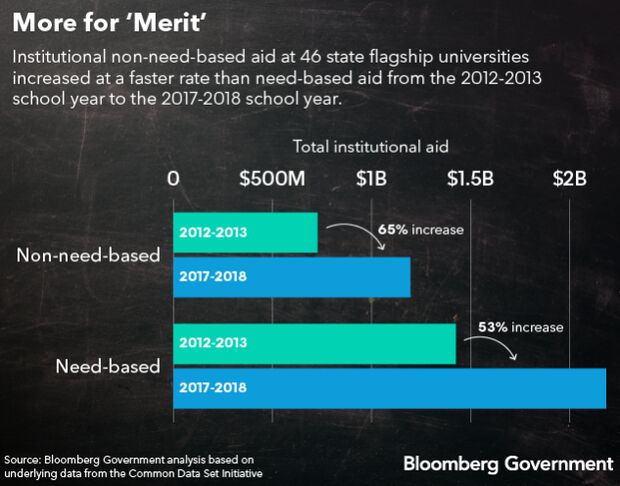

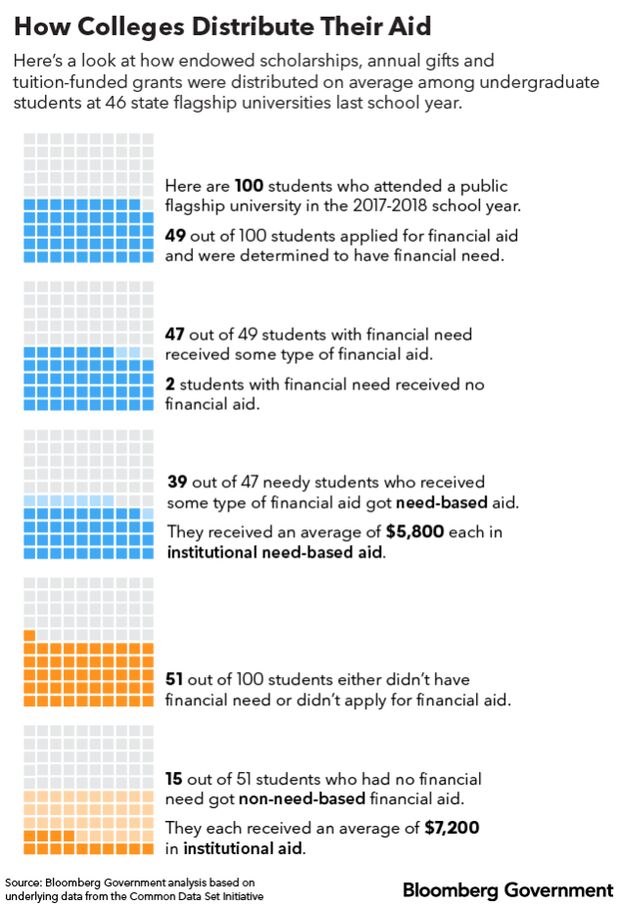

Forty-six state flagship universities gave $1.2 billion in aid that was not tied to a student’s financial need in the 2017-2018 school year, a 65% increase from five years before, according to a Bloomberg Government analysis of data schools submitted through the Common Data Set Initiative. For students that colleges assess as lacking financial need, the average award was $7,200, up from $6,100 in 2012-2013.

Non-need-based aid is often used to attract students with strong academics, athletic abilities, or other talents to help raise schools’ positions in national rankings, which can help increase enrollment. It also can help a school’s bottom line by attracting wealthier students who tend to pay more tuition even with the aid, say education experts.

This creates a dilemma: Should public universities give money to students who don’t need it and maintain fiscal health? Or should that aid go to students who can’t afford to attend college without it?

“Of course, we would like to be meeting every student’s need,” Hecker said. “We track the average gap between expected family contribution and the cost of coming here, and we try to do our best to close that gap, but we can’t always do it.”

Maine hasn’t neglected low-income students—the university increased need-based aid to $26 million, a 71% bump, and increased the size of the average financial aid award. Among state flagship universities, often the largest public college in a state and frequently a land-grant school, need-based aid rose 53%, to $2.2 billion, with the average student in 2017-2018 getting $5,800 in need-based aid, up from $4,000 five years prior, according to the analysis.

Not all public flagships are increasing merit aid or using it in the same way. Several top-tier flagships—such as the University of North Carolina and the University of Virginia—are able to cover all financial need that students might have. But those are the exceptions.

Optimizing Tuition Revenue

Funding for public colleges has taken a hit in recent years. The largest federal grant program for low-income students only covers a maximum of 60% of the average in-state tuition at four-year public colleges, a drop from the 92% it covered two decades ago, according to the College Board, a non-profit education company.

State support for higher education, which was slashed during the Great Recession, has only half recovered, leaving public colleges in a majority of states more dependent on tuition than on state and federal appropriations, according to a 2019 report from State Higher Education Executive Officers Association.

The result is tuition and fees have become the largest source of revenue for public four-year colleges, data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows. Tuition made up nearly 21% of revenue at public four-year colleges in 2017-2018, an increase from 16% a decade ago. State funding dropped to 17%, from 23%. And federal grants and contracts declined to 8% from 12%.

As tuition becomes more important, so does finding students who can pay more of the cost of college without help from the school, said Nathan Mueller, a principal at EAB, an education consulting firm.

“Public universities, probably even more than private colleges, are in a circumstance where net tuition revenue really has increased in importance for the funding they need to continue their operations,” Mueller said. “Merit aid becomes a tool for optimization of net tuition revenue outcome.”

Complex Funding System

To understand how some colleges increase tuition revenue by giving away aid, it helps to understand the practice known as “tuition discounting.”

If a college inflates its tuition prices, it can then offer potential students “discounts” through aid. The aid, sometimes presented as a scholarship, entices wealthier students to come to the school, although they may ultimately pay more than their low-income peers who might have received larger need-based aid packages.

The tactic also has a psychological benefit for the students—studies have shown that students would rather get a $10,000 scholarship to a $20,000 school than simply attend a $10,000 school.

The cost of attending a four-year public school—tuition, fees, room and board—was $21,400 in the 2017-2018 school year, according to the College Board. Yet few students will pay full tuition. The average student—after receiving federal, state and school aid—paid a little less than $15,000.

Don Hossler, who served as vice chancellor of enrollment services at Indiana University and wrote a book on strategic enrollment management, said colleges initially used discounting and merit aid as a Robin Hood strategy—wealthy students paying slightly less than full tuition were subsidizing those from low-income families. But he said not all schools still use the strategy.

“The whole tuition discounting has gotten totally out of control,” he said. “It’s a terrific example of prisoners dilemma—everyone knows it’s happening, but no one wants to do anything to unilaterally disarm.”

Aid Questioned

That can also hurt low-income students, who often don’t have easy access to advanced placement classes, extracurricular activities, and other resources that look good on college applications, said Tiffany Jones, director of education policy at The Education Trust.

Public four-year colleges gave merit aid to about 13 percent of students in the 2015-2016 school year. A quarter of students with family incomes of $100,000 or more received merit aid from their schools in 2015-16, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. For students with family incomes of less than $20,000, fewer than 11 percent got merit aid.

“We should be spending financial aid on students who face the highest financial hurdles,” Jones said. “Not students who have had the biggest head start.”

Releasing Pressure?

While merit aid has increased overall among flagships, some public colleges are aiming to focus more on serving low-income students. The Association of Public Land Grant Universities, which includes 239 public research universities, announced an initiative last year to increase access to college and boost equity.

But reducing merit aid can be difficult for many tuition-dependent colleges that must compete with other schools in a given area, said Pamela Horne, who spent her career working on student enrollment at colleges like Purdue University, the University of Michigan, and Michigan State University.

“You do worry. Is my enrollment going to shift? Are the students that we enroll going to come to us not as well prepared? Is our honors program going to be happy with the top scholars we got? Are faculty going to be happy with the students we’re admitting? Are we even going to make the size class that we want?” she said. “To shift from merit aid to need-based is a pretty scary proposition for somebody in my business.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Emily Wilkins in Washington at ewilkins@bgov.com; Madi Alexander in Washington at malexander@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John Dunbar at jdunbar@bloomberglaw.com; Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com