Providers Beg Congress to Save ‘Breakthrough’ Virtual Heart Care

- Congress failed to include cardiac rehab in omnibus bill

- Program can address No. 1 killer of Americans, provider says

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The end of the Covid public health emergency this spring comes with a slew of high-profile changes that will take millions of people off Medicaid and end free over-the-counter Covid tests for those on Medicare.

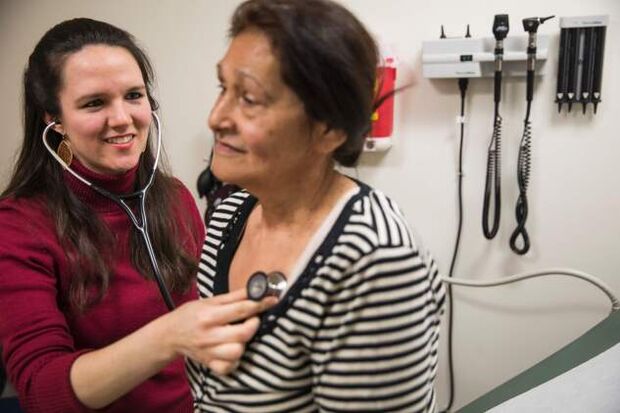

But the expiring declaration also terminates smaller programs, including one that could have an impact on the No. 1 killer of Americans: heart disease. Under the Covid emergency, anecdotal evidence suggests more people were able to participate in virtual services to get supervised exercise and counseling meant to improve heart health and prevent future heart attacks.

For physician and researcher Dean Ornish, the change in offering such cardiac rehabilitation was “a real breakthrough” in reaching seniors on Medicare who wanted to avoid going into a hospital, or couldn’t get to one.

“We’ve been limited to reaching people who live within driving distance of one of the hospitals or clinics, or physician groups we’ve trained to do this,” said Ornish, who for 45 years has studied how lifestyle changes, such as altering diet or exercise habits, affect people’s overall health. Ornish heads Ornish Lifestyle Medicine, which trains health-care providers to do cardiac rehab.

Much of these gains could disappear on May 11, when Medicare coverage for certain telehealth services such as cardiac rehabilitation will end, along with the White House Covid emergency declaration. The popularity of those services has underlined new ways of reaching patients—and also new areas of growth for the health industry capitalizing on temporary changes to Medicare policy.

Earlier: White House Will End Covid Emergency, Border Measure in May

Congress late last year extended many of these temporary Medicare changes through the end of 2024 as part of the omnibus spending bill (Public Law 117-328), namely giving people in rural areas access to telehealth services. But in the usual last-minute legislative rush, cardiac rehab wasn’t one of them. Hospitals now say they’ll have to stop offering it virtually.

“The vast majority of cardiac rehab programs will have to cease, unless something is done,” said Ed Wu, chief medical officer and co-founder of Recora, a company that enables health systems, hospitals, and physician officers to deliver cardiac rehab virtually.

Ornish, other telehealth providers, and some medical societies are lobbying Congress to add cardiac rehabilitation and a related program called intensive cardiac rehabilitation to a list of telehealth services Medicare covers. They argue Medicare could save lives and keep thousands of seniors out of hospitals and operating rooms by letting them get such services virtually.

Underused Heart Program

The public health emergency on Covid meant that since early 2020, Medicare beneficiaries in any area—not just rural communities—could get telehealth services. Medicare also expanded the list of services that could be covered via telehealth, and included cardiac rehab in that list.

With millions of Americans sheltering at home in the midst of the pandemic, telehealth use for office and outpatient visits spiked to as much as 17% by mid-2021, up from about 2% at the end of 2019, according to data from McKinsey. That’s a shift of about $250 billion in health care moving virtual, the analysis found.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the US, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC and Medicare hope to prevent a million deaths between now and 2027 via practices that reduce heart disease, in part by promoting services such as cardiac rehabilitation.

The program typically comprises 36 one-hour sessions, usually in a hospital outpatient center designed like a gym that includes exercise training, skills development, and counseling on stress management. Those who complete the rehab have a 47% lower risk of death from heart disease, and are half as likely to have a heart attack three years afterward, the CDC advertises on its website.

Evidence shows the service is vastly underused: a 2020 study found only about a quarter of the 366,103 people in Medicare who were eligible to receive cardiac rehabilitation participated in the program, and about 27% of those few participants completed it.

The pandemic appeared to have shifted that trajectory—though Wu, from the cardiac rehab company Recora, cautioned that not enough time has elapsed for published studies on the issue. Though Recora launched in 2019, Wu said the service really took off in 2020 after Medicare, a major payer, loosened its telehealth rules.

Recora has facilitated as many as 50,000 virtual sessions, Wu said. His clients have also reported more cardiac rehab patients: Geisinger Health System, with hospitals in central and northeastern Pennsylvania, has more than tripled its cardiac rehab patient load since going virtual, according to Wu. A spokesperson for Geisinger confirmed this figure.

Push for Medicare Overhaul

Cardiac rehab practitioners aren’t the only ones lobbying Congress for changes. Physical therapy, physicians’ groups, and other medical lobbies are likewise asking Congress to expand Medicare’s telehealth offerings permanently.

Justin Elliott, vice president of government affairs for the American Physical Therapy Association, said he expects a slew of bills this Congress to add various services or specialties individually to the list of covered telehealth care. Physical therapy was among the services for which Congress granted temporary coverage by Medicare late last year.

Elliott said the next focus will be working with lawmakers on a permanent change to the program’s payment structure.

However, congressional aides for key panels say long-term changes to Medicare’s pay—particularly ones that could cost billions of dollars by expanding what the program covers—aren’t likely to be an immediate priority. Two aides to separate health committees in the House and Senate say it’s unlikely Congress will take up many telehealth bills this Congress because most telehealth services will continue to the end of 2024, making it a problem for the next Congress.

Groups lobbying around the issue say the market for telehealth services has grown too large for lawmakers to ignore.

“I don’t know how you put the toothpaste back in the tube,” said Elliott.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Ruoff in Washington at aruoff@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.