Private Equity’s Billions Are Fueling New Space Industry Boom

- Federal contract spending nurtured tech, shows path to revenue

- SpaceX, company alums helped refine investor pitch for space

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to grow your opportunities. Learn more.

After spending decades quietly building intelligence satellites for the US government, the technology contractor now called Maxar branched out.

Its spacecraft and programs helped fishing boat captains find fertile waters, radio listeners access more stations, and Covid-19 researchers identify desolate neighborhoods. Maxar satellites were credited last year for capturing proof of Russian soldiers looting ports and slaughtering Ukrainian civilians.

Growth came at a cost. The publicly traded company had borrowed heavily; its debt threatened to slow it down. Then the global private-equity firm Advent International swept in with a $6.4 billion bid, a per-share markup of 129%. Maxar said its new owners will accelerate development of groundbreaking technology and products.

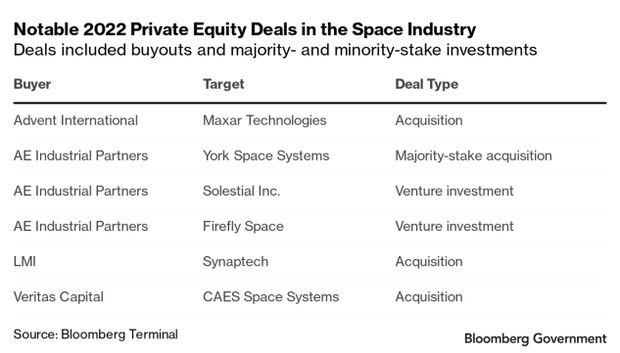

It was the latest example of how private equity sees space as its next lucrative frontier, and how that infusion of money could hasten its influence on everyday life. The last two years have brought a flurry of new private investments in space companies, as inflation and supply-chain issues have dampened the enthusiasm for other sectors, and also because many space contractors have long-term government contracts to sustain them.

“Smart private equity firms coming into this sector is a good thing, right? Despite it being more competitive,” Kirk Konert, a partner at AE Industrial Partners, a Florida-based investment firm active in the field, said in an interview. “It creates more M&A activity, more founders coming to the table to sell. They have more options, right? All that’s great for the ecosystem.”

Since its acquisition last month, Maxar has already sped up the timeline for releasing its next two satellites, and touted plans to use satellite and 3D mapping technology to develop a high-quality “digital twin” of the planet. One purpose, it says, will be for gamers “to play the whole Earth and users to meet anywhere in the metaverse.”

Private equity is no stranger to the space industry, but the latest surge ends what had been a lull caused by erosion in the satellite communications industry and a scarcity of other business lines worth investing in.

“It was certainly dormant for some years,” Caleb Henry, senior analyst at Quilty Analytics, a boutique consultancy serving the space and satellite industry, said in an interview.

That changed in part thanks to Elon Musk’s SpaceX. From its outset in 2002, the startup was focused on finding a way to drive down costs of space operations, opening the door to governments and companies that once had no way to afford it.

Co-founder and CEO of Phantom Space Jim Cantrell helped form that early team.

“They had a hobby of building rockets in the desert—not talking the ones you put on your desk but that could pick up your whole garage,” he said. “That became SpaceX.”

Earlier: SpaceX Alums Leverage Background, Network in Procurement Arena

Out of that culture, Musk’s team embarked on developing a host of technological innovations to make launch more reliable and affordable, from the rockets and hardware needed to do it to the software behind it all. And landing big contracts with NASA gave the company stable funding to grow.

An analysis by the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies found that by 2010, SpaceX advancements had cut the costs of sending a payload into low-Earth orbit to $2,600 per kilogram, about half what it was at the start of the decade. In 2018, costs for Tesla’s Falcon Heavy rocket came in at just $1,500 per kilogram.

That opened the door to a boom.

Venture capital helped launch so-called Earth Observation satellite companies like Spire and HawkEye 360, which specialize in tracking everything from pollution and climate change to illegal fishing operations and industry-wide logistics and supply-chain operations.

Others backed asteroid-mining and space junk management companies, which focus on helping operators deal with debris in increasingly crowded orbits.

Roughly 10 times as many satellites have been launched into orbit annually in recent years compared to a decade ago. The FCC reported more than 4,800 satellites in orbit as of September, and FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel said the commission had 64,000 applications for new satellites.

SpaceX alums are part of the driving force. In one example, AstroForge, which is working to develop tech for asteroid mining, was co-founded by former SpaceX alumnus Jose Acain. The company also continues to have an impact, particularly as its satellites get smaller and cheaper.

SpaceX’s Starlink satellites were able to beam internet access into Ukraine after Russia’s invasion. The company also announced it was working with T-Mobile to bring satellite connectivity to smartphones, something Apple is also integrating into the iPhone.

As the sector grew, private equity took notice.

Companies like AE Industrial Partners and Arlington Capital Partners, with years of expertise investing in federal defense and aerospace contractors, started seizing so-called buy-and-build opportunities—acquiring a collection of complementary companies and combining them in the hopes of building something worth more than the sum of its parts.

AEI, based in Florida, acquired eight space-related firms across 2020 and 2021, re-branding the combined venture as Redwire Space, a company specializing in hardware manufacturing and infrastructure to help others scale up their space operations. Others invested in up-and-comers or bought firms that appeared to be on a good trajectory.

The biggest driver is a boom in spending by government agencies whose objectives now include space technology and developments.

The Department of Defense boosted its spending—showcased in the creation of the Space Force and Space Development Agency—while agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration joined the surge in interest, spending big on Earth observation satellites tracking weather patterns, natural disasters, and flooding.

“You go where the government is focused on investing,” Ryan Hoffman, managing director of Chertoff Capital, the investment arm of the security and geopolitical consultant group headed by former Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, said in an interview. “On the defense tech side, space technologies are very much an in-demand area.”

The Space Development Agency, for example, was formed in 2019 to tackle the space portion of the Defense Department’s missile defense initiative. Its spending on unclassified contracts soared to $1.3 billion in the last fiscal year, up from just $74.7 million two years earlier, according to Bloomberg Government data.

That spending fuels its National Defense Space Architecture, a multi-phase missile defense program using a series of satellite constellations to be launched every two years.

The entire DOD has spent more than $34 billion on missile and space systems research and development since fiscal year 2019. China, Australia, and countries across Europe are also getting in on the boom.

“The fact of the matter is government—whether that’s civil or defense, and whether that’s US or globally—drives space activity,” said Konert, the AEI partner.

Around the same time AEI got started on its space investing, DC-area Arlington Capital began work building BlueHalo, a space tech and mission services company that’s brought in more than $102 million in unclassified government contract awards since fiscal 2019, according to Bloomberg Government data.

In July, PE portfolio company LMI won a bidding war for Colorado space tech firm Synaptech, which specializes in software and mission control for military operations, and is building a platform that catalogs and helps devise travel plans that founder Zac Gorrell compared to Expedia in space. Terms of the acquisition weren’t disclosed.

Maxar’s sale to Advent International, announced Dec. 15, topped them all.

Private-equity investors have at times been accused of hurting their target’s long-term prospects by either squeezing them too tightly or saddling them with unsustainable debt. They often also go into the process with goals in mind; AEI took Redwire public via special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, less than a year after forming the venture.

Maxar and Advent declined requests to discuss the company’s future. But Maxar said at the time of the acquisition that its new owners want to accelerate development, and the deal already appears to have had an impact.

Maxar is now pushing up the launch of its next two satellites, part of its Earth imaging work that’s used by governments and companies to track operations and events from natural disasters to logistics and supply chain lines.

Industry insiders say it’s not likely to be the last big space deal—thanks to the still-brewing headwinds of rising interest rates, fears of recession, a struggling stock market, and the insulation from it that comes with government and defense contracts.

“Space is viewed as the ultimate high ground,” Henry said. “You see a lot of investors willing to commit for the long haul to these companies.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Caleb Harshberger at charshberger@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John P. Martin at jmartin@bloombergindustry.com; Amanda H. Allen at aallen@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – the intel you need to win new federal business – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.