NASA $4 Billion Uranus Voyage Could Be Windfall for Space Firms

- NASA to announce decision in July, contract scramble to follow

- ‘Revolutionary’ 13-year trip could launch as soon as 2031

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to grow your opportunities. Learn more.

NASA is poised within weeks to declare whether it will launch a $4.2 billion mission to Uranus that supporters say could unlock previously unknown questions about our solar system, and one certain to launch a dogfight among space contractors.

LISTEN: Josh Axelrod reads his story on NASA’s mission to Uranus

A panel of the world’s leading scientists endorsed the ambitious flagship exploration this spring, and NASA’s response is expected next month. If approved, the 13-year journey could begin as soon as 2031. But how NASA decides to build the spacecraft—and whether it continues the trend of farming out more mission-related contracts to the private sector—depends in part on Congress’ level of support.

David Murrow, senior manager of business development for deep space exploration at Lockheed Martin, said NASA has been “trying to think about a new way of doing business and using its money more effectively.”

NASA recently handed contractors Axiom Space and Collins Aerospace an award that could be worth as much as $3.5 billion to design new spacesuits. It also gave SpaceX a $2.9 billion contract to build the lunar lander that will deliver astronauts to the moon as part of the Artemis program.

Some of the decisions about how much of the design will be led in-house at NASA through an institute like its Jet Propulsion Laboratory and how much handed to contractors will no doubt be shaped by the funding decisions in Congress.

Purse Strings

NASA missions have generally drawn bipartisan backing from the House and Senate. It’s not clear if the midterm elections would affect that.

Rep. Don Beyer, the Virginia Democrat who chairs the Science, Space, and Technology Committee’s Space Subcommittee, was optimistic lawmakers would approve the Uranus project. Reading the possibilities outlined in the mission recommendation, he said in an interview, “I felt like a kid in the candy store.”

His Senate counterpart is Sen. John Hickenlooper of Colorado, who chairs the Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Space and Science. Hickenlooper said in an interview he supports the mission, but that he’s “more focused on some of the issues that are right in front of us now,” including NASA’s program to land astronauts back on the moon for the first time in more than 50 years.

Even if the GOP wins control of Congress in November, Republicans have signaled their willingness to green-light the plan. Rep. Robert Aderholt of Alabama, who would be in line to become chair of a House appropriations panel, said in a statement provided to Bloomberg Government that supporting NASA priorities like the proposed Uranus mission “is important to both the research community and the future of exploration.”

That’s another potential benefit to getting the deep space exploration program up and running, advocates say: A Uranus mission would help cultivate America’s workforce of scientists and engineers, while inspiring the next generation of future scientists.

“Four billion dollars sounds like an immense amount of money,” Hickenlooper said. “But when you look at the benefit of having not just thousands, but literally millions of kids tuning into science, it becomes one of the most affordable things you can imagine.”

Trekking to the Outer Solar System

Shrouded in clouds and spinning on a skewed axis, Uranus sits 1.8 billion miles from Earth. It was visited only once before, in a brief 1986 fly-by that produced a few photos.

The recommendation to return came in April from the Decadal Strategy for Planetary Science and Astrobiology, a report by the world’s leading scientists in the field. While its recommendations are not binding, the survey is commissioned every 10 years by NASA and the National Science Foundation to get a sense of the scientific community’s wishlist.

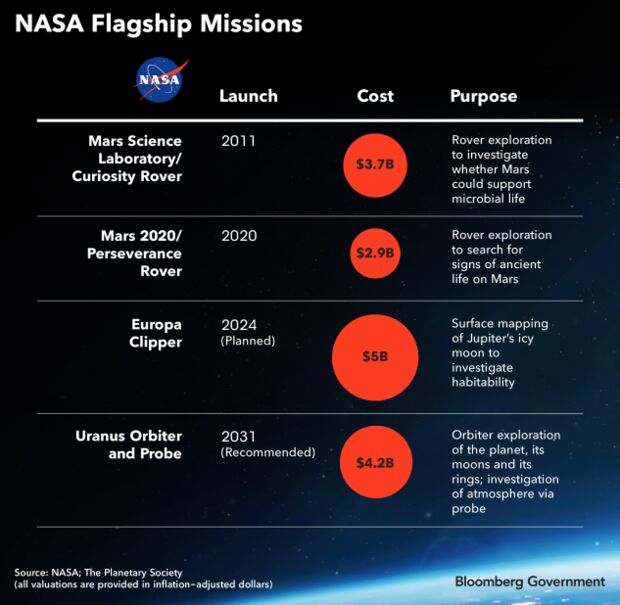

The same group recommended NASA’s last flagship project in 2011, a $5 billion mission to Jupiter’s moon that’s now scheduled to launch in 2024. Previous flagship missions sent rovers to Mars and canvassed the solar system with probes.

Sending an uncrewed orbiter and probe to the solar system’s coldest planet will be nothing less than a “revolutionary scientific expedition,” said Jonathan Lunine, a Cornell University astronomy professor who led the group of scientists making the Uranus recommendation.

That’s because ice giants Uranus and its neighbor Neptune, while completely different from the rest of our solar system, bear the closest resemblance to most planets detected in others.

“By being able to orbit Uranus, we’re really going to gather the ground truth that provides the context for all the planets we’re discovering elsewhere around other stars,” Hampton University professor of planetary science Kunio Sayanagi said. “That’s a big scientific motivation.”

Building the Spacecraft

The decadal’s recommendation elicited cheers from key private firms who have been bankrolling concept studies and readying their space teams for a new suite of lucrative contracts.

Murrow said his staff has spent years looking at trajectories and mission concepts for a potential ice giant mission. Since the decadal’s report this spring, he said, “The fire is lit more strongly.”

The closest comparison to the Uranus proposal was mission that sent a probe to Saturn in 1997, said Kathleen Mandt, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins’ Applied Physics Lab. NASA directed that flagship mission out of its Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and hired Lockheed Martin to build the launch vehicle. The European Space Agency led the design of the probe, contracting out assembly to the French company Aerospatiale.

International partners are expected to again join the conversation if NASA green-lights the Uranus project next month.

The European Space Agency and Australian Space Agency both expressed interest in participating in the mission, perhaps by leading and contracting out the design of the probe and its instruments.

“There are actually excellent places for synergies,” said Guenther Hasinger, director of science for the European Space Agency.

One challenge will be ensuring the probe has enough power when it gets too far to rely on solar rays for propulsion.

Development of rovers on Mars raised similar questions. Space contractor Aerojet won a $6.6 million award in 2014 to power the Perseverance Rover, using thermal energy generated from slowly decaying plutonium when dust storms on Mars have blocked out the sun.

The Chinese didn’t take such steps, and their rovers went dormant during storms, said Joe Cassady, Aerojet’s executive director for space.

“Our rovers are running,” said Cassady. “They’re perfectly fine to run through the dust storms. And that’s the kind of technology that we’d be applying to these outer planet missions.”

Sailing so far away from the Sun isn’t the only quandary about heading into the outer solar system. Equipment will also have to be designed to be much more durable than usual to last such a long flight time.

Scientists have also discussed the use of aerocapture, a technique similar to using a planet’s orbital pull, to propel the spacecraft. This approach, not yet proven in space, would take advantage of Uranus’s atmosphere to put the spacecraft into orbit and reduce flight time, but would first require much more modeling and study of the planet’s atmosphere.

Two Timelines

NASA won’t officially reveal its decision until July, but an agency spokesperson hinted at the plan, telling Bloomberg Government the decadal “will inform a compelling new chapter in planetary science.”

Mark Hofstadter, a NASA scientist who studies Uranus’ atmosphere, said he was confident lawmakers will support the project. His bigger concern was the timing of the launch.

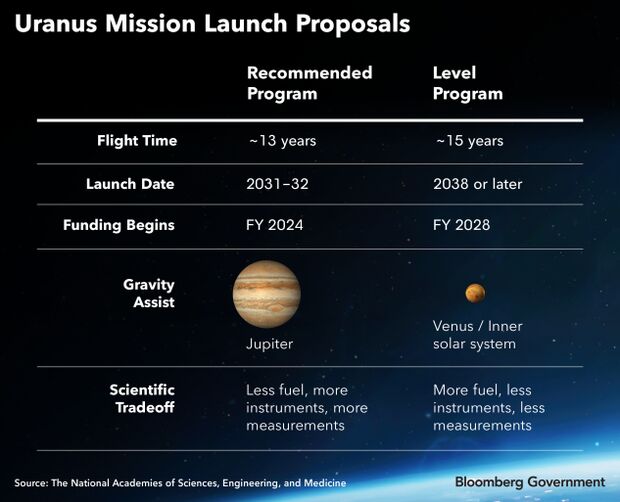

The decadal laid out two possible timelines. One would have Congress approve the $4.2 billion price tag in fiscal 2024 and a spacecraft launch as soon as 2031 and fly for approximately 13 years. That launch window would benefit from the orbital alignment of the planets and use Jupiter’s gravitational pull to boost the spacecraft.

Congress could also opt to delay the funding until fiscal year 2028. That would push the launch to 2038 or later and add two or three years to the flight time, forcing NASA to use a gravity boost from Venus or some other planet in the inner solar system.

Beyer said he believes the earlier timeline is likely, but acknowledged that might be “unrealistically optimistic.”

What could push the Uranus mission to the later launch or even sideline the project entirely are cost overruns and delays from the Artemis program, a $93-billion mission scheduled to carry the first woman and person of color to the moon in 2025.

A later Uranus launch means NASA would lose the advantage of the Jupiter gravity boost, thus requiring more fuel and a smaller, lighter spacecraft. Those constraints would limit the number of instruments the vessel could hold, how many measurements scientists can make, and how many different places the spacecraft could visit in the outer solar system.

‘We’re Going to Learn a Whole Lot’

Scientists prioritized the mission in part because it doesn’t require any scientific breakthroughs or Nobel Prize-worthy discoveries. Its rewards could be immeasurable anyway, they say. Uranus could help piece together the puzzle of how our solar system formed.

By taking measurements of the planet’s atmosphere, researchers intend to learn more about when and where each planet developed, whether Uranus and Neptune switched places at one point, where planets have migrated, why Uranus sits at a near-90 degree tilt, and more.

Of course, there wasn’t universal consensus on targeting the 7th planet from the sun for NASA’s next flagship mission.

A contingent of decadal authors were rooting for Neptune, as Uranus’ farther neighbor addresses a lot of the same elusive scientific questions. Ultimately, they agreed to recommend the mission that wouldn’t need to use the hugely powerful but so-far unproven Space Launch System to travel even farther into the outer solar system.

“We had to go with the one that would be most realistic, that we could get done now, so that we don’t have to wait a decade or more to possibly send a flagship to one of the ice giants,” Mandt said. “And it had nothing to do with preferring one planet over the other—’cause we love both of them.”

Above all, planetary scientists emphasize just how strange Uranus is.

“The interior of the planet, the atmosphere, the rings, the magnetosphere—we’ve seen things that we don’t think should exist,” Hofstadter said. “Our current understanding of how planets work, things we see at Uranus and Neptune violate that—so we’re going to learn a whole lot by going there.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Josh Axelrod in Washington at jaxelrod@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John Martin at jmartin@bloombergindustry.com; Amanda H. Allen at aallen@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – the intel you need to win new federal business – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.