MMT Makes Democrats Curious Amid Debate on Health Care, Climate

Expensive measures such as “Medicare for All” and the Green New Deal are among the issues facing the House Democrats who will weigh the fiscal aspects of the party’s most ambitious ideas now that they control the majority.

But the rise of Modern Monetary Theory within the party has some lawmakers wondering whether it even matters whether those programs increase the deficit, as long as the country isn’t at risk of significant inflation.

Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT, is almost never mentioned specifically by members of Congress who negotiate budget and appropriations measures, but it is working its way into the mainstream political debate. Now, it’s gotten some Democratic lawmakers’ attention as the party considers big-ticket policy priorities. That includes House Budget Chairman John Yarmuth (D-Ky.), who will decide over the next few weeks whether to produce a fiscal 2020 budget resolution that maps out the caucus’s fiscal vision for the future.

“It sounds like there is a lot of validity to it,” Yarmuth told reporters in February. “The problem I see with it is that ultimately it all could work until it doesn’t. And when it doesn’t, it would take congressional action to correct it, and that’s far from guaranteed.”

MMT holds that because the federal government issues its own currency, it can never run out of money, and therefore the potential for inflation is a bigger problem than rising deficits. From a policy perspective, a federal jobs guarantee is a central feature of MMT, acting as an economic stabilizer. The theory also emphasizes lawmakers’ flexibility to spend on domestic priorities such as the expansion of health coverage and an ambitious climate program.

Yarmuth said he understands the appeal of MMT, but acknowledged it could be “extremely risky” when it comes to inflation. If inflation sets in because the economy is flush with cash, it would be difficult for lawmakers to agree to significantly raise taxes in order to limit the numbers of dollars in circulation, he said.

Yarmuth said he’s considering holding a hearing on the topic because of MMT’s growing popularity.

Confused? Here’s What You Need to Know About Modern Monetary Theory

Big-name economists and political figures have largely been much harsher than Yarmuth when describing MMT. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell called the concept “just wrong,” in February. Lawrence Summers, the former chief economist of the World Bank and an economic adviser to Democratic presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, called it “fallacious at multiple levels” this month.

But the theory may have more traction among lawmakers in the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, who face questions about how they’ll pay for their most ambitious ideas. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), who champions “Medicare for All” and the Green New Deal, told Business Insider in January that MMT “absolutely” needed to be “a larger part of our conversation.”

Ocasio-Cortez’s comments were MMT’s biggest, most direct endorsement in Congress, said Stephanie Kelton, former chief economist for the Democrats on the Senate Budget Committee under ranking member Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.). Kelton is one of the most vocal and high-profile MMT proponents.

Budget Outlook

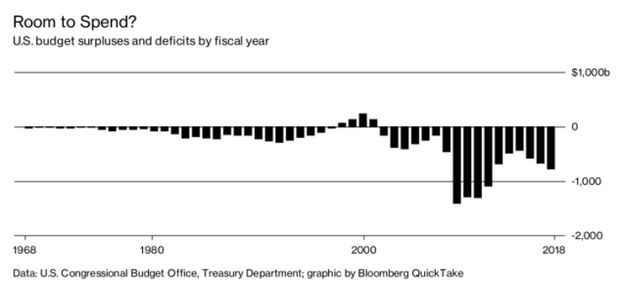

The federal government’s red-stained balance sheet may be the primary reason some Democrats are skeptical of the typical criticisms of deficit spending. The deficit is projected to be $897 billion in fiscal 2019, 4.2 percent of gross domestic product, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Debt held by the public is estimated at $16.6 trillion in fiscal 2019, or 78.3 percent of GDP. If Democrats produce a budget resolution, Yarmuth has already said there’s no way it will project to balance anytime in the next decade.

Yarmuth said earlier this month there’s a 50-50 chance House Democrats adopt a budget resolution. Defense spending is a key wedge among the caucus, but the party’s inclination to call for broad mandatory and discretionary spending increases in the face of steep deficits also makes the measure unappealing.

Even if Yarmuth doesn’t produce a budget resolution, the Congressional Progressive Caucus is working on its own document. That caucus includes some members who are at least interested in MMT, if not outright evangelists.

Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), a Budget Committee and Progressive Caucus member, has called for a federal jobs guarantee and has praised Kelton’s work. But he was careful to emphasize that he believes there are dangers to having a large deficit and debt, when asked about MMT.

“I do think deficits matter — deficits matter in that they are inflationary — and that deficits matter in that the interest that we pay on the debt crowds out other investments that we could be making,” Khanna said. “That said, I do think that we had a period of austerity politics when we didn’t have a large enough stimulus and that led to a slower recovery than needed, and so I’m sympathetic to the critique that we should have had a much larger stimulus.”

A jobs guarantee is a central facet of MMT. Fans of the theory say such a program would act as an automatic economic stabilizer, increasing spending during downturns and decreasing when private employment is high. That automatic action theoretically would address Yarmuth’s concern that Congress wouldn’t act to address potential inflation.

Khanna said he hopes House Democrats produce a budget resolution and take it to the floor for a vote. The party needs to articulate what kind of deficit spending it supports and what measures could reduce the deficit, he said. That includes “getting out of the endless wars” and repealing the tax cuts enacted during Trump and Bush administrations (Public Laws 115-97 and 108-27), while investing in the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, federal funding for universities, and in “ creating jobs in a transition from an industrial to a digital age,” he said.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), another Budget Committee member and the co-chair of the Progressive Caucus, also warned against austerity, saying the idea that cutting spending is always a good thing is “simplistic.” A Democratic budget resolution should “make it clear that Democrats stand for investing in our people, investing in education, health care, transportation, jobs, all of that.”

PAYGO, CBO Scrutinized

Aside from the shout-out from Ocasio-Cortez, bigger things may be on the horizon for proponents of the theory, even if it’s not mentioned by name, Kelton said in a phone interview. The fight over a Pay-as-You-Go rule in the House — requiring spending cuts or revenue increases to offset the cost of new legislation — was a significant moment, she said. The House rules package included a PAYGO requirement, despite objections from progressives, but House Rules Chairman Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) in January said he was open to waiving the rule for major Democratic priorities including “Medicare for All.”

Jayapal also introduced a bill (H.R. 242) that would repeal the statutory PAYGO requirement (Public Law 111-139) that all new legislation in a given Congress that makes changes in taxes, fees or mandatory spending must not increase projected deficits.

The PAYGO fight reflects a growing push for lawmakers to make important investments without attaching unrelated, arbitrary spending cuts, Kelton said.

“It’s not about being, quote, ‘for MMT,’” Kelton said. “It’s about understanding enough to know that the federal budgeting process is very broken, and that shackling yourself with self-imposed rules like PAYGO are going to make it impossible to move progressive legislation — ambitious, bold legislation.”

Kelton has also previously called on Congress to “abandon” the CBO scoring model and “recognize that the risk of overspending is inflation, not bankruptcy.”

Lawmakers’ focus on piecing together a series of pay-fors to offset the cost of legislation “is an incredibly stupid way to make public policy, and tax policy in particular,” Kelton said in the interview.

Republican Pushback

Republicans have already begun to criticize the idea that Democrats would push major legislation without any pay-fors. Senate Budget Chairman Mike Enzi (R-Wy.) even referred specifically to the debate over MMT in a hearing earlier this month.

“More and more, I’ve been hearing people claim that debt and deficits don’t matter,” Enzi said. “This unconventional view is not only misguided; it’s dangerous.”

Without mentioning MMT, House Budget Committee ranking member Steve Womack(R-Ark.) effectively expressed the opposite philosophy in a March hearing, arguing the deficit was a sign of dangerous, out-of-control spending, even if the effects hadn’t shown up in the inflation rate yet.

“As the Congressional Budget Office warned earlier this year, our nation is nearing a fiscal crisis. I would argue we’re already in one,” Womack said. “It may not seem like one. The markets haven’t responded yet. But I sense that there’s some smoldering going on that could lead to a potential raging fire, as it were, regarding the nation’s deficit and debt.”

Womack’s line of thinking is common in Congress. CBO Director Keith Hall told lawmakers in a January hearing that the likelihood of “a fiscal crisis” is rising and that the U.S. is “on an unsustainable course.” And Yarmuth, the Democrats’ top budget writer, has used similar language warning of a fiscal “emergency.”

But as younger progressives push for ambitious health care, jobs and climate programs, an acceptance of deficit spending may prove appealing. And when it comes to the previously fringe theory of MMT, Yarmuth says, “I’m willing to be convinced.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Jack Fitzpatrick in Washington at jfitzpatrick@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Zachary Sherwood at zsherwood@bgov.com; Jodie Morris at jmorris@bgov.com