Mastriano’s Pennsylvania Campaign Relies on Avoiding Questioning

- Governor candidate kept digital-only focus after primary win

- Republican airtime lags behind Democrats’ in some states

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Some Republicans running for governor have kept a low profile—skipping debates, refusing to take reporters’ questions, and spending little on traditional campaign ads.

In Arizona, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Michigan,, the Republican candidates’ TV airtime lags well behind the Democrats’ ad spending, according to the tracking service AdImpact. Even in states inundated by GOP campaign spots — such as Arkansas, Iowa, Nebraska, Ohio, and Wisconsin — unless voters are plugged into social media channels where campaigns control the talking points, they may not hear the candidates handling unscripted questions.

Pennsylvania’s GOP gubernatorial nominee, Doug Mastriano, may be the best example of the campaign strategy evolving from a general distrust of the press.

Like former President Donald Trump (R), who will campaign for him on Nov. 5 in Latrobe, Pa., Mastriano perpetuates claims of bias in social media posts aimed at die-hard supporters. It’s a noteworthy strategy in part because Pennsylvania, the fifth-most populous in the country, could be a crucial battleground state in the next presidential election, as it was in 2020.

Some high-profile Democrats in races across the country have declined to debate opponents who have said Joe Biden didn’t win the presidential race. Mastriano’s approach goes further and has been in place for the whole campaign.

“If Mastriano wins, I think people are going to rush to two things: One, they’re going to try to do this ‘don’t talk to the press and only go digital to your followers’ thing. And then two, I think they’re going to try to gravitate toward more extreme positions, thinking that is the route to win,” said Samuel Chen, a GOP political strategist who’s worked for former US Rep. Charlie Dent and US Sen. Pat Toomey.

Mastriano’s core promises are a total abortion ban, more drilling for oil and natural gas, and a total overhaul of election laws.

He made his name on social media with live video chats during the early days of the pandemic, when he was a relatively new state senator after beginning his term in 2019. He added to his following with limited personal appearances and by accepting interviews only with conservative news outlets before winning in a nine-candidate primary field in May.

He stuck with those tactics for the general election.

Mastriano’s campaign didn’t respond to requests for an interview, nor has he done interviews with any of Pennsylvania’s major media outlets. He refused to debate his opponent, Attorney General Josh Shapiro (D), unless he could choose his own moderator.

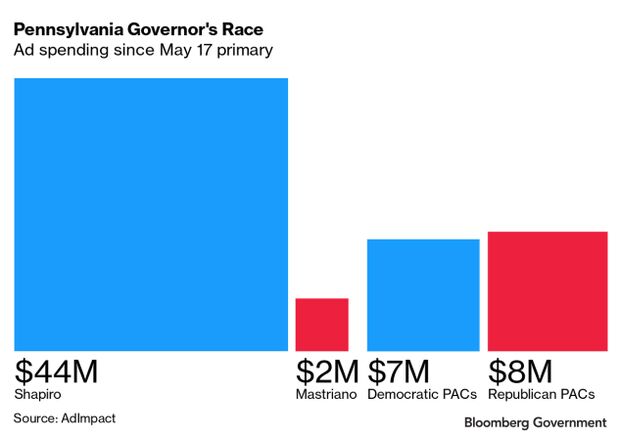

Mastriano only recently began running TV ads, spending just over $1.6 million since the primary, compared with Shapiro’s $44 million in ad spending since then, according to AdImpact. President Joe Biden (D) and former President Barack Obama (D) will campaign for Shapiro and other Democrats in Philadelphia on Nov. 5.

A PAC supported by the conservative Commonwealth Partners Chamber of Entrepreneurs ran a few ads attacking Shapiro, without mentioning Mastriano’s name. But they’ve been unhappy with Mastriano’s approach, said the group’s president and CEO, Matt Brouillette.

Mehmet Oz, whom Trump endorsed for an open US Senate seat in Pennsylvania, has used the airwaves to compete for voters through attack ads raising questions about his opponent, Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, while there’s been no similar effort from Mastriano, he said.

“Unfortunately, he hasn’t campaigned to reach those voters,” Brouillette said.

Mastriano’s social media posts highlight his focus on his Christian faith and military service, his plan to withdraw Pennsylvania from a regional climate change pact, and his promises to give parents more power in education.

In particular, he wants them to be able opt their children out of programs that teach critical race theory or that include what he’s called “government overreach” for mandating masks during the pandemic and allowing transgender students to play on girls’ sports teams.

His posts also have said Democrats should have focused on voters’ concerns about inflation and crim rather than investigations into Trump and the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol..

Mastriano used campaign money to bus supporters to Trump’s rally just before the attack, and he’s among 14 Republican candidates running for key offices nationwide after pushing to overturn the presidential election results, according to the Bloomberg Election Risk Index.

“He has some views that he’s passionate about. What he prioritizes are certainly not necessarily what the vast majority of Republicans or independents are talking about,” Brouillette said. “But on the general messages of inflation and jobs and energy and education, those absolutely are, and that’s where vast majority of voters are at when you look at the polling and what matters to people.”

‘Objective Messages’

It’s not what Mastriano says or posts online so much as where he’s not saying it that’s hurting his campaign, said Charlie Gerow, a GOP political strategist who ran in Pennsylvania’s gubernatorial primary. He now supports Mastriano.

“A lot of voters tend to tune out the 30-second ads that they get bombarded with on a moment-by-moment basis, but they pay more attention to what they consider more objective messages from the candidate, and they come through interviews and opportunities to talk on camera,” Gerow said.

Nothing in Mastriano’s digital-only approach attempts to breach a divide with independents, swing voters, or the Republican Party establishment, said Alison Dagnes, a Shippensburg University political scientist and author of several books on political media.

“What he’s basically saying to the voters of Pennsylvania is, ‘I’m just reaching out to the people who not only already like me, but who already speak a language that I know half of Pennsylvania does not speak,’” she said.

“If he wins, then not only is this about the age of social media, this is a spotlight on how angry and divided we are,” she said.

`Least Engaged’

The problem with a digital-only campaign is that many voters don’t see much of Mastriano, said Samuel Rhodes, a Moravian University political scientist who studies social media algorithms and filters.

More platforms are available now than when Trump campaigned in 2016 and 2020, but it’s political partisans who look to social media or political news outlets for updates from the candidates, while independents just go about their day, he said.

“Independents tend to be the least politically engaged, and part of the reason is they’re just not reading the news as much as the rest of us,” he said. “They probably watch the local news, generally speaking.”

It would be a mistake to try to replicate Mastriano’s strategy without examining midterm election turnout, other races on Pennsylvania’s ballot this year, and whether Democrats stumbled in their own campaigns, Chen said.

“Things like that are crucial in understanding what works in a campaign,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jennifer Kay in Miami at jkay@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Katherine Rizzo at krizzo@bgov.com; Loren Duggan at lduggan@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.