Manchin’s Pipeline Could Be the Last of Its Kind, if It Survives

- Mountain Valley natural gas project approaches finish line

- Powerful senator pushes gas as clean-energy solution

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

West Virginia native Mark Jarrell bought 98 acres of green fields and undulating hills overlooking the Greenbrier River about 20 years ago, envisioning a retirement compound of sorts where family and friends could live, camp, and visit.

“That’s my version of the American dream,” Jarrell said in May, standing in the doorway of his custom-built home in Pence Springs, West Va. “And a pipeline company can come and kick it out from under you.”

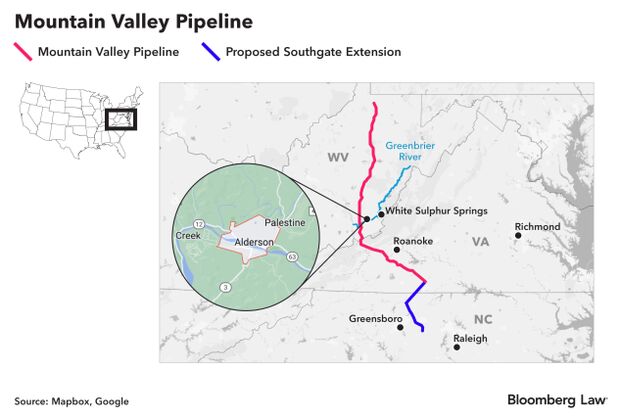

Winding beneath the roughly five acres of his land that offer the most stunning views is part of a 42-inch, 303-mile natural gas pipeline, proposed to run through West Virginia, Virginia, and part of North Carolina. The valley below holds a final test for the eight-year-old Mountain Valley Pipeline project: federal approval to cross the 1,250-foot-wide river, among the widest of hundreds of water bodies the pipeline must still traverse.

True to its name, the pipeline project has crested steep mountains and dove into narrow valleys carved by crystal-clear Appalachian creeks and rivers. Construction in such challenging terrain has triggered landslides and erosion, inspiring the sorts of protests and legal challenges that killed the Atlantic Coast, PennEast, and Constitution pipelines.

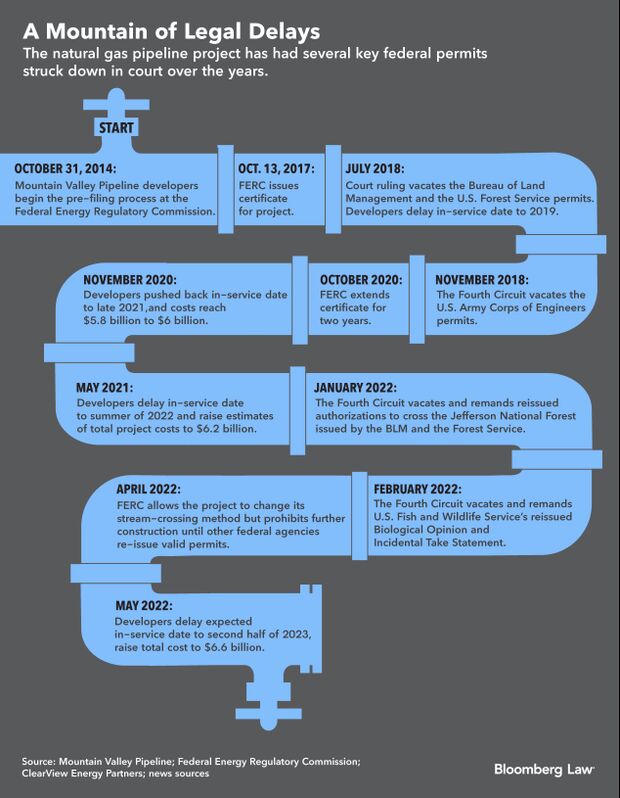

MVP could be the last major pipeline constructed on the East Coast and possibly the US, as natural gas faces an uncertain future in the transition to renewable energy. The pipeline is $3 billion over budget with a current price tag over $6 billion, and is somewhere between 50% and 90% complete, depending on whom you talk to. Developers have asked the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to extend its certificate by another four years — a request the commission will have to answer before the current authorization expires in October.

Brandon Barnes, a Bloomberg Intelligence senior litigation analyst, put at 80% the chances of FERC giving the four-year extension, in a Aug. 2 report. If that happens, the coalition behind the pipeline looks to begin operations in the first quarter of 2023.

‘We Don’t Know What’s In Our Future’

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) is a key supporter with unusual political sway, at least for the moment, in a Senate evenly divided between the two parties. He’s touted the MVP as an important vehicle to deliver gas domestically and abroad as the Ukraine war and the global energy crisis continues. Pipelines are the “safest form of transport” for energy, he and other supporters like to say.

Ultimately, approval will rest on whether the project can clear its permitting hurdles, requiring input from the Army Corps of Engineers, the Environmental Protection Agency, Fish and Wildlife Service, and FERC. The project also has encountered challenges related to state permits.

A deal on climate and energy investments in the Inflation Reduction Act between Manchin and Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) was contingent on a separate federal permitting reform agreement that Democratic leaders expect to unveil in the fall and include in a government funding package.

Earlier: Mountain Valley Pipeline Shield in Manchin Deal Raises Hackles

While the deal may not necessarily speed up permits, its proposed shift of any legal appeals to the D.C. Circuit and away from the Fourth Circuit — which struck down multiple permits — represents a “real boon” to the project, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Expediting Mountain Valley was key to winning Manchin’s support for the climate deal, though the pipeline wasn’t specifically mentioned in draft bill text obtained by Bloomberg.

“I would like to think Mountain Valley would be top of the heap because it’s complete, it’s ready,” Manchin said during a July 28 call with reporters. “It can be in production in six months.”

Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W.Va.), who is from the state’s shale-rich northern Panhandle, says “there is just no way” MVP would be the last of its kind.

“We don’t know what’s in our future,” as far as energy development, Capito said, recalling the shale boom in 2008. Capito gave a hypothetical example of new natural gas or hydrogen development happening somewhere without a pipeline. “You have to transport it. Pipeline is the way to do it.”

Pressuring FERC

The US pipeline network is massive. More than 210 systems snake through the lower 48 states, with about 3 million miles linking production areas and storage facilities with consumers, according to the US Energy Information Administration. In 2021, natural gas accounted for 38% of electricity generated in the US, followed by coal at 22%.

The Mountain Valley project has tested the legal limits of federal agencies that review and permit those pipelines, with some of the most contentious arriving at FERC, a five-member independent agency. Since 1999, FERC has issued certificates for nearly 500 projects that span about 23,000 miles of new pipeline, with capacity to move about 286 billion cubic feet of gas a day, according to commission data.

Richard Glick, FERC’s Democratic chair, voted to extend the MVP certificate in 2020, though he dissented on the commission decision to allow developers to resume construction. Glick will likely have to make a decision on a second extension soon, before appearing before Manchin for a high-stakes confirmation hearing.

This year, FERC’s new 3-2 Democratic majority advanced updates to its gas policy that promised greater scrutiny of a project’s environmental justice impacts and set a greenhouse gas emissions threshold that would trigger a stricter environmental review. But after Manchin called a hearing to lambast the commissioners, they walked back the stricter gas policy. Glick told Manchin he was trying to boost legal certainty after a string of appeals court rulings went against gas projects, including Mountain Valley.

Earlier: Energy Regulators Revamp Much-Criticized Gas Review Policy (2)

Environmental groups have pressed FERC to consider leaks of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, as well as environmental justice impacts. On the other hand, the industry has urged the commission to not delay, touting gas as a cheap fuel source for utilities and consumers, and cleaner-burning than coal.

After FERC authorized Mountain Valley in 2017, a federal appeals court in Richmond sided with environmental groups and struck down federal permits from multiple agencies to cross water bodies and the Jefferson National Forest. FERC requires projects to obtain valid permits before allowing them to go into service.

The commission’s online docket for the project has received thousands of comments. Members of the Beyond Extreme Energy organization disrupted normally staid commission meetings in Washington. Groups including the Sierra Club and the Protect Our Water, Heritage, Rights coalition tracked court proceedings and company statements as inching toward what they saw as the inevitable cancellation of the project.

The Sierra Club has received funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, the charitable organization founded by Michael Bloomberg. Bloomberg Law is operated by entities controlled by Michael Bloomberg.

In May, activists marched near the pipeline route during the two-week Walk for Appalachia’s Future. “We really believe this is the year it’s make-or-break,” said Grace Tuttle, program and development coordinator for the POWHR coalition, which has opposed the pipeline for years. “This project is not inevitable. We don’t have to carry bad ideas through just because that’s the status quo. There is so much we are still fighting to save.”

But Mountain Valley’s lead partner, Equitrans Midstream Partners LP, has every incentive to keep going, said Christi Tezak, managing director of ClearView Energy Partners.

While other canceled pipelines were developed by gas-consuming utilities and faced greater pushback from state officials, Equitrans is part of the biggest US gas producer, EQT Corp., based in Pittsburgh. A gas producer ending a project that’s largely in the ground would be like abandoning a mostly-built house because of rising costs.

Read More: Public Lands, Waters Become Flashpoint in Global Energy Debate

“It’s a logic problem on the part of the opponents,” Tezak said.

Equitrans spokeswoman Natalie Cox declined to make project developers available for an interview or to answer written questions.

Pipeline Politics

The politics of pipelines have never divided neatly along party lines.

Virginia’s Democratic senators, Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, have both criticized the MVP’s public engagement efforts and permitting process while not opposing the project.

Warner said this week that any gas pipeline project “must abide by applicable federal and state laws and regulations, and be safe for communities and the environment.” MVP “lacks multiple federal authorizations required to finalize construction,” he said.

A Kaine spokesperson said the senator believes litigation over the pipeline stemmed from a flawed process, and improving that process is preferable to lawmakers deciding the outcomes of individual projects.

House Natural Resources Chairman Raul Grijalva (D-Ariz.) said he’s concerned the permitting reform deal Schumer and Manchin agreed to “is just another euphemism for gutting our most foundational environmental and public health protections, like the National Environmental Policy Act.”

But the federal permitting labyrinth and endless litigation on pipeline projects is a chronic problem, Capito and Manchin said.

Capito said there should be one agency in charge of ensuring that all permitting is performed and submitted in a timely fashion, similar to how the process works for highways. Pipeline permits and decisions ping-pong from one agency to another because of different court decisions and agency silos, causing decade-long delays in some cases.

Manchin said permitting reform needs to balance environmental protection with moving US energy security. If a project ultimately isn’t going to work, he said, “don’t you think you should know before you’ve taken down and invested billions of dollars and then get stopped at the end?”

‘Time for It to Happen’

Jarrell is worried the steep slopes of his land could shift around the already completed pipeline. On May 29, 2020, FERC inspectors discovered “some subsidence” on his property along the pipeline route, including a deep crack in the soil, according to a FERC report. “Mountain Valley is tracking erosion and subsidence on restored right-of-way but is not certain when those issues can be corrected,” the report stated.

The company initially offered Jarrell roughly $100,000 for five acres of his property — an easement — to run the pipeline underground. Jarrell refused. Eventually MVP confiscated that land through eminent domain. He received an undisclosed amount of money through arbitration.

Jarrell says many of his neighbors affected by the pipeline reached some sort of financial agreement.

“I was just naïve and thought that in America you had certain rights,” said Jarrell, who remains upset over the use of eminent domain.

Capito said “property rights are a concern” but “the companies that have come to the table have worked obviously with a lot of people to get 95% of those questions answered.” She said most MVP opposition is from outside of West Virginia and is “part of a bigger national trend to disrupt any pipeline, no matter what the value.”

In the end, the global energy crisis and domestic politics could propel MVP into operation.

“We have energy here in our country,” said Rep. Carol Miller (R-W.Va.), who represents the state’s 3rd congressional district, through which much of the pipeline runs. “And I think it’s time to stop the federal freezing on all the projects, and let it move.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Kellie Lunney in Washington at klunney@bloombergindustry.com; Daniel Moore in Washington at dmoore1@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com; Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.