Lobbyists’ Revolving Door Leads Back to Capitol Hill Jobs

- 110 advocates became Capitol Hill aides since 2018 election

- Democrats’ regaining House majority likely drove movement

Lane Lofton valued his experience as a top lobbyist for a top tech industry group, but after Democrats took over the House majority in 2018 he was quick to head back to Capitol Hill and become the top aide to freshman Rep. Joe Cunningham (D-S.C.).

“My heart is on the Hill,” said Lofton, who most recently worked for NCTA – The Internet & Television Association.

He joins more than 100 staffers who traded in jobs with high-paying K Street firms, corporations, trade associations, or nonprofits — like Common Cause and Heritage Action for America — for long hours on Capitol Hill beset by partisan brawls and legislative gridlock.

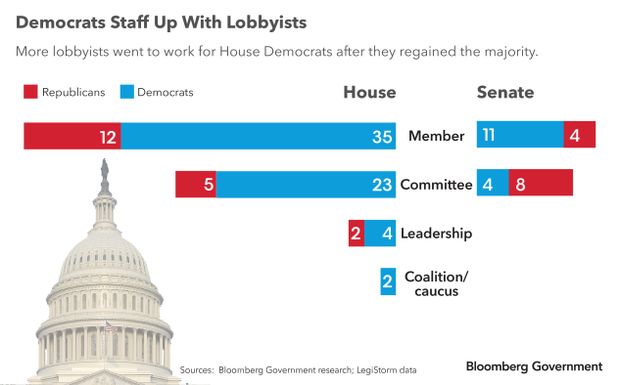

Nearly 60% of the 110 people who’ve moved to the Hill from the influence industry since the midterm election went to work for House Democrats, according to data analyzed by Bloomberg Government, a likely result of the flurry of new jobs available after the party regained control of the chamber. Republican offices in both the House and Senate hired 31 ex-lobbyists, or 28% of the total number who moved over.

Some say they’re doing it out of a desire to be in public service or because they have a longtime loyalty to their congressional bosses, and have even taken a pay cut to do so.

Lofton said his hiring pitch to Cunningham was that there is “a lot of value to someone who has been a part of the legislative process on both sides.”

Cunningham — who has sworn off money from lobbyists as well as corporate and leadership PACs — also hired two other ex-lobbyists as policy aides: one from the National Wildlife Federation and another from CoBank, a cooperative bank that’s part of the U.S. Farm Credit System. Nine other freshman House Democrats who took a pledge to reject corporate cash have hired lobbyists, though not all of those new staffers represented industry interests.

‘Ticket Punched’

House Majority Whip James Clyburn (D-S.C.) brought on three ex-lobbyists, two of whom are familiar faces.

Ashli Palmer left her government affairs job at CVS Health Corp., where she had been since 2017, to rejoin his staff as director of floor operations. Senior adviser Michael Hacker, a former partner at public affairs firm HDMK, last worked for Clyburn in 2011.

Almost all of the advocates-turned-aides have held jobs on the Hill or in the federal government before, and some have gone back and forth from the private sector multiple times, according to data from congressional tracking website LegiStorm. Most declined to comment or did not respond to a request for comment.

“The reverse revolving door is a tried and true way to get your ticket punched and set yourself up for your next position,” said Meredith McGehee, the executive director of Issue One, a campaign finance watchdog.

Lobbyists who’ve held multiple government jobs “recruit more clients, clients from a variety of economic sectors, and charge more per client,” says Tim LaPira, an associate professor at James Madison University who co-wrote the 2017 book “Revolving Door Lobbying.”

Keeps on Turning

Once a lobbyist returns to Capitol Hill, McGehee adds, “the question that immediately arises is, how do you set aside both the loyalties and the benefits through salary that you have received from that private interest?”

Congress has made no conflict-of-interest rules limiting the interactions of lobbyists returning to Capitol Hill. “Unlike the executive branch, there are no reverse revolving door restrictions or cooling-off periods for lobbyists-turned-staffers,” said Craig Holman, a lobbyist at public interest group Public Citizen.

“A strong reverse revolving door policy should apply to Congress and senior staff,” he added. “The conflicts of interest are the same.”

Former Cornerstone Government Affairs lobbyist John Keast became the GOP staff director on the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee in December. He earned more than $619,000 in compensation and benefits from the firm in 2018, according to a financial disclosure form, and reported an additional $1.8 million payout stemming from sale of equity in Cornerstone in 2016.

Keast has a long history with Chairman Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), working on his 1994 House campaign and then as his chief of staff and adviser until 2006.

“I was honored that Chairman Wicker has the trust and confidence in me to help him on the Commerce Committee,” Keast wrote in an email. “I’m glad I was in the position to be able to answer the call to public service again.”

Congressional staff salaries are generally capped so they don’t exceed a member’s pay.

Backgrounds Vary

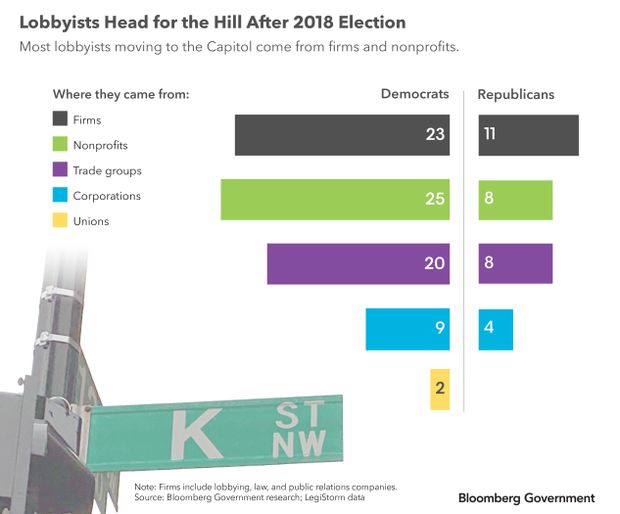

Democrats are most likely to have come from nonprofits like Defenders of Wildlife and the Center for Responsible Lending, and trade associations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Council of Life Insurers. Meanwhile, most Republicans came from lobbying firms, such as Rich Feuer Anderson and Monument Advocacy.

Navis Bermudez, who started working for Democrats on the House Transportation Subcommittee on Water Resources and Environment in January, her previous gig was serving as the deputy legislative director at the Southern Environmental Law Center, where she earned roughly $127,000 in 2018, according to a financial disclosure. In her new role, she took in about $108,000 from January through September, congressional records show.

Both parties have recruited staff from corporate positions. The policy director and general counsel for Democrats on the House Small Business Committee, Naveen Parmar, came from Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co., where he was an in-house lobbyist. He’d previously worked for Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) and the House Ways and Means and Small Business committees.

Catherine Fuchs, the counsel for the Republicans on the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee, most recently worked as a lobbyist for BNP Paribas S.A., a French banking company.

Dan Meyer, chief of staff to House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), worked at the Duberstein Group, Inc., where he represented clients like the Business Roundtable, Chinese conglomerate Alibaba Group Holding Limited, Honeywell International Inc., Caterpillar Inc., and Pfizer Inc. He was previously the White House director of legislative affairs under President George W. Bush and chief of staff to former Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.).

“I’m going to work for Kevin McCarthy, so I don’t feel any need to carry any water for former clients in this job because my client is now Kevin McCarthy and the House Republicans,” said Meyer, who’s known McCarthy for more than a decade. If a former client came to talk about a specific policy, he adds, he wouldn’t participate.

Asked how he feels about conflict-of-interest concerns and the idea of setting himself up for his next K Street job: “I’m not planning to go back to lobbying,” he replied.

To contact the reporter on this story: Megan R. Wilson in Washington at mwilson@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Adam Schank at aschank@bgov.com; Bennett Roth at broth@bgov.com