Insuring Millions After Pandemic Key to Democrats’ Spending Plan

- Spending package aims to forestall health insurance loss

- Medicaid grew to reach nearly 83 million during pandemic

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The rewrite of Medicaid rules included in House Democrats’ sweeping social spending and tax package would make safety-net programs in red states look closer to their blue-state counterparts.

This $270 billion expansion of public health insurance programs for lower income and disabled people—more than 80% of the health care-related spending in the package—includes measures to stop states from tightening restrictions on their Medicaid programs when the Biden administration ends the Covid-19 public-health emergency.

The changes would forestall a sudden drop in coverage for millions of Americans when the federal government’s contributions to state Medicaid programs return to pre-pandemic levels. They’re aimed at Americans who see increases to their income that might disqualify them from Medicaid in some states but aren’t enough to afford many private plans.

“These are all incredible changes to our health care system that will save lives,” Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, told reporters recently.

The Medicaid-related spending goes largely to two priorities: bolstering home- and community-based care and expanding the Affordable Care Act’s tax credits to allow people living in the dozen states that didn’t expand Medicaid to get subsidized private health plans that mimic the program’s no-cost benefits. Those policies are coupled with significant changes to how states cover pregnant women and children.

The package awaits action in the Senate, where Democrats hold the slimmest-possible majority. Republicans say the spending package is too expensive and warn it could exacerbate the cost of health-care services.

The changes are long overdue, Pallone said, but Democrats haven’t been able to reach bipartisan agreements on them this year.

BGOV OnPoint: House Passes Tax and Social Spending Bill

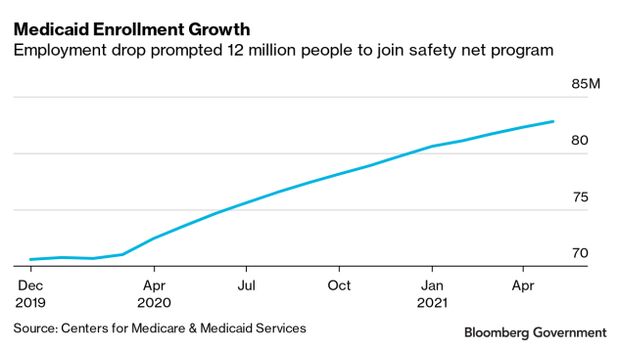

Medicaid Enrollment Grows

The spread of Covid-19 and subsequent drop in employment levels across the U.S. led to historic levels of Medicaid enrollment.

Between February 2020—when Covid-19 was beginning to circulate widely in the U.S.—and May of this year, 12 million people were added to Medicaid rolls across the country, according to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. Nearly 83 million people were enrolled in the program, which is primarily run by states, with the federal government footing a portion of the bill, according to CMS.

This surge in enrollment was caused by lagging employment—people lost income and were newly eligible for the program—and a law that offered federal dollars to states if they didn’t drop people from the program, said Frederick Isasi, executive director of Families USA, a health-care advocacy organization that has worked with Democrats and the Biden administration on issues facing Medicaid this year.

That coverage, crucial to ensure people could seek medical services if they got sick with Covid-19, could be uncertain next year, he said.

“Medicaid was really the linchpin protecting millions of families during the pandemic and what this does is make sure that’s not pulled out from them when they still need it,” Isasi said of the spending package.

Declaring an end to the Covid-19 public-health emergency would end the increased federal Medicaid dollars and the requirement that states keep people in the program even if their eligibility changes. In response, Isasi said many states will likely take on what are called redeterminations—efforts to check who is eligible to stay on the program.

The public health emergency will end in January if it isn’t extended.

Some states may make little effort to reach Medicaid recipients, resulting in a purge of beneficiaries who don’t respond to a letter or phone call, Isasi said. Some are likely to hire contractors specifically to purge the ineligible, with little effort to direct them to other programs that offer low-cost coverage, he said.

“We don’t want to see millions of people lose coverage with redeterminations that are really just meant to shrink the program,” he said.

The spending package would taper off the higher federal share for Medicaid starting in March, with requirements around redeterminations meant to transition people onto other coverage options. States that adopt stricter eligibility standards or procedures for their Medicaid programs any time before 2026 would lose some federal dollars under the legislation.

When the boosted federal Medicaid dollars end, many states will face a budget crunch that will pressure them to cut people who are no longer eligible for the program, said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors.

The spending package largely means they’ll need to hire new staff to do a massive outreach campaign in 2022, he said.

“This is making sure 85 million people get the right coverage,” Salo said. “That would mean doing eligibility checks in a reasonable, humane way.”

Safety-Net Hospitals Face Cuts in Democrats’ Bill, GOP Warns

Maternal and Child Health

The spending package also contains changes to Medicaid meant to improve the health of children and pregnant people that Democrats have sought unsuccessfully to make into law for years.

It would ensure all pregnant and postpartum Medicaid enrollees receive a full year of coverage after their pregnancy ends and make coverage for children last 12 months, instead of six months or less. About half of states currently provide continuous coverage for children and 26 states have already applied to offer 12 months of Medicaid coverage postpartum, according to records from the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families.

Rep. Robin Kelly (D-Ill.) has pushed for years to get postpartum coverage and funding for programs to support training and diversification of the perinatal workforce, as well as other changes aimed at improving maternal health for women of color.

Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to be uninsured, which leads to avoidance of needed health services and higher death rates, particularly among pregnant people, Kelly said. The pregnancy-related death rate among Black women is more than triple that of White women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“It’s completely unfair and unacceptable,” Kelly said.

Kelly has been an advocate for the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act (H.R. 959), which would have enshrined the 12 months of postpartum Medicaid coverage, but said the legislation never won support from Republicans in Congress.

The spending package is Democrats’ best chance to see it through, Rep. Annie Kuster (D-N.H.) said.

“These issues historically were very bipartisan—we were able to reach deals where we saw issues,” Kuster said. “Something is going on where they don’t want to come to the table.”

Democrats’ Slimmer Home Health Care Plan Hinges on State Uptake

Republican leaders have decried the spending package as too expensive and far-reaching.

Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), ranking member of the Energy and Commerce Committee, complained in a markup of unrelated bills that she and Pallone had reached a deal on a five-year extension for Medicaid funding for Puerto Rico, only for Pallone to take on this slate of Medicaid changes as part of the spending package that Democrats are advancing on their own.

“I hope that this is the last time Democrats walk away from our bipartisan agreement,” she said earlier this month.

The spending package addresses Medicaid funding for U.S. territories permanently.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Ruoff in Washington at aruoff@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Sarah Babbage at sbabbage@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.