Impeachment Spotlights Vulnerability of Acting Federal Watchdogs

- Permanent inspectors general absent in several departments

- While legal status same, advocates worry acting IGs reticent

When Senate Minority Whip Dick Durbin pulled the Pentagon’s internal watchdog into his office in late October to request he investigate the department’s withholding of military aid to Ukraine, he got an answer he wasn’t expecting.

No.

The Ukraine money had sparked an impeachment inquiry in the House just weeks before, and acting Defense Department Inspector General Glenn Fine told Durbin the House needed to investigate the subject.

Durbin wasn’t pleased. While he said Fine has had an illustrious career, refusing an investigation request from Congress raises the question if his status as an acting official—who can be more easily fired than a confirmed one on the whim of his boss, the president—was interfering with the IG’s role as described in law, Durbin said.

“It really takes away some of their independence,” Durbin said, adding that Fine is vulnerable politically because of “this administration’s appetite for acting secretaries.”

“It really takes away some of their independence,” Durbin said, adding that Fine is vulnerable politically because of “this administration’s appetite for acting secretaries.”

The impeachment inquiry surrounding President Donald Trump has spotlighted the pivotal role of the cadre of more than 70 often under-the-radar internal watchdogs whose job is to investigate executive branch agencies. It was a whistleblower report flagged to Congress by the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community in September that kicked off the impeachment probe.

Lawmakers, former IGs and good government groups said they are especially concerned about acting inspectors general such as Fine, who can be less vetted, more easily removed and feel more pressured not to investigate the administration than those who are permanent. Even having the job on a permanent basis provides no guarantees of protection. The New York Times reported Nov. 12 the White House had mulled firing the intelligence watchdog after he brought forward the whistleblower complaint.

“When these difficult circumstances come along, it’s important to have confirmed inspectors general to put them in a better position to make such difficult decisions, especially when it regards matters that might relate to impeachment proceedings,” said David Walker, a former U.S. Comptroller General. From that perch, Walker headed the Government Accountability Office, which conducts similar oversight of federal agencies.

Fine’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment. In a letter to Durbin, he said the decision not to open a probe was made out of concerns that it could interfere with or duplicate the House’s impeachment investigation.

Impeachment Déjà Vu

While IGs existed before Richard Nixon’s impeachment, the broad expansion of the IG corps into major agencies took place after Watergate stoked public outcry for more oversight of fraud and abuse within the executive branch.

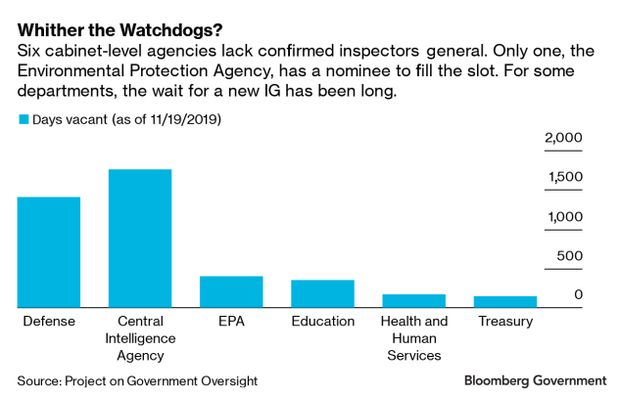

Inspector general vacancies have been stubbornly high, no matter the party in power, in part because executive branches are often at odds with the role’s investigative work, said Joel Brenner, former inspector general of the National Security Agency in the George W. Bush administration. The 11 current vacancies,including six at cabinet-level agencies like Defense, Treasury and the Environmental Protection Agency, is similar to numbers during the Obama administration, according to data from the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) and a 2018 GAO report. About half of the IG offices require Senate confirmation of presidential nominations, while the other half are appointed by lower officials.

The difference now is that the plethora of allegations against President Donald Trump’s administration is spotlighting the importance of the role.

“We now have an administration that’s deeply hostile to the civil service in general and to anybody who can second guess anything that they might do, lawful or unlawful,” Brenner said. “So these are important positions, especially important to fill now.”

The Trump administration’s aggressive stance toward inspectors general began with an attempt before Trump’s inauguration to remove them en masse, an extraordinary though ultimately unsuccessful move. A 2018 report from Democrats on the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee said the White House targeted inspector general offices for budget cuts. The Departments of Education, Interior and the EPA, among others, have tried to replace acting watchdogs in the middle of investigations or refused to cooperate with their information requests.

Job Jeopardy

Acting watchdogs have the same authorities to conduct investigations, but their exposure to being instantly removed by the President—whereas Senate-confirmed posts require a 30-day delay and a report to Congress—weighs on the official’s independence, said Rebecca Jones, policy counsel at POGO. An acting IG may not want to jeopardize their job or their agency’s budget by pressing for investigations disliked by the president, she said.

An acting IG can also be installed without the same vetting process needed to pick a permanent individual, which exists to ensure the person is nonpartisan, demonstrates integrity and has appropriate skills, said Stanford University law professor Anne Joseph O’Connell, referring to the 1978 statute that establishes the post.

“It’s both the front end and back end protections I worry about,” said O’Connell, who is also a member of the Administrative Conference of the United States, an independent federal agency that aims to improve government function.

For example, in January, the Department of Education moved to replace the acting inspector general with its own deputy general counsel. The idea was dropped after conflict of interest concerns from Democrats as the IG was investigating the department’s reinstatement of an accreditor of several failed for-profit colleges.

Walker, who as comptroller sued Vice President Richard Cheney in 2002 for failure to turn over information about his White House energy task force, said if he had been acting at the time, “for any human being, that would’ve affected their willingness and potential ability to do it.”

The watchdog vacancies have stirred bipartisan congressional concern. Trump was pressed to quickly nominate individuals to fill positions in a Sept. 13 letter from members of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee. The House Oversight and Reform Government Operations subcommittee questioned the head of the council representing the watchdogs at a Sept. 18 hearing on the openings.

“Various developments with respect to IGs in the last few weeks underscore the need to have above-the-fray, politically untainted, nonpartisan neutral experts who can call balls and strikes as they see it,” said Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.), who chaired the oversight hearing.

“‘Acting’ makes somebody look over their shoulder, ‘acting’ makes all opinions tentative,” Connolly said.

Overseeing the Overseers

To be sure, the majority of acting inspectors general and employees surveyed at their offices indicated in a 2018 GAO report that the acting status had no impact on their work, and that they did not think acting watchdogs were inherently less independent. However, a similar majority also indicated the acting investigators were less independent in appearance, and some reported the situation negatively impacted work output.

Stanford’s O’Connell, Jones and some former watchdogs say Congress should take steps to ensure acting IGs are more fully vetted and have similar protections as permanent ones. Bipartisan legislation (H.R. 1847) that would increase reporting on inspector general vacancies and aims to incentivize the nomination process passed the House in July, but has yet to be considered by the Senate.

For now, lawmakers are keeping a close eye on overseeing the overseers, and continuing to request investigations. A group of Senate Democrats last week renewed a call for another impeachment-related investigation to a department IG, this time at the Department of Justice.

“There have to be some places left in the U.S. government where you go there and get an honest opinion,” Connolly said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Michaela Ross in Washington at mross@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Jonathan Nicholson at jnicholson@bgov.com; Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com