Hollowed-Out Staffing Crimps USDA Relief Programs for Farmers

- Retirements, low pay blamed for chronic understaffing

- Five-year reauthorization also seeks to address climate issues

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

American farmers have a message for the Agriculture Department: Fill the empty chairs plaguing your local offices.

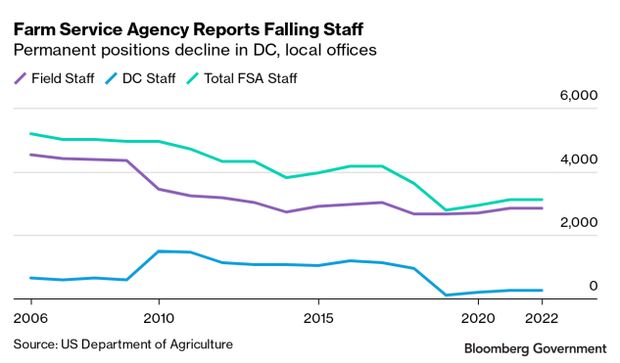

A wave of retirements and an inability to keep pace with private-sector salaries have caused staffing to plunge at key offices. The Farm Service Agency, which provides front-line help to farmers nationwide, now has 2,000 fewer workers than it did in 2006, a nearly 40% decline.

Advocates are urging the incoming Congress to tackle the shortage in the 2023 farm bill, the legislative package reauthorized every five years to calibrate the government’s agriculture funding and policies. The American Farm Bureau Federation, the country’s largest agricultural lobbying group, has deemed the USDA staffing shortage a top priority on its 2023 to-do list.

Read More: Farm Lobby Targets USDA Staffing, Food Aid Issues for 2023 Bill

The department’s county-level technicians and staffers conduct on-site inspections, assist with property appraisals, and help new farmers navigate the application process for government loans and land-conservation subsidies. For many, it’s also “the only place in counties and rural America that you can have direct access to your federal government,” said Chris Gibbs, an Ohio farmer and former FSA employee who chairs the advocacy network Rural Voices USA.

The personnel shortages could become even more pronounced as the department begins to roll out more than $18 billion in climate-smart conservation assistance and more than $5 billion in targeted loan relief from Democrats’ party-line Inflation Reduction Act package from August (Public Law 117-169). Both are expected to increase the program workload for agencies. But it’s unclear if they will also fund more staff.

Dave McLaughlin, a farmer in south central Pennsylvania, said he spent about $1,800 on a private contractor to help update conservation plans for his property about five years ago because the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, which typically offers such assistance, was taking so long to review them.

The expense wasn’t make-or-break for McLaughlin, who grows soybeans, corn, wheat, and grass. But for some other small farmers, the agency’s subsidized services are invaluable, he said.

“The cost-share programs are really needed to make it financially feasible” to keep operations environmentally friendly, McLaughlin said.

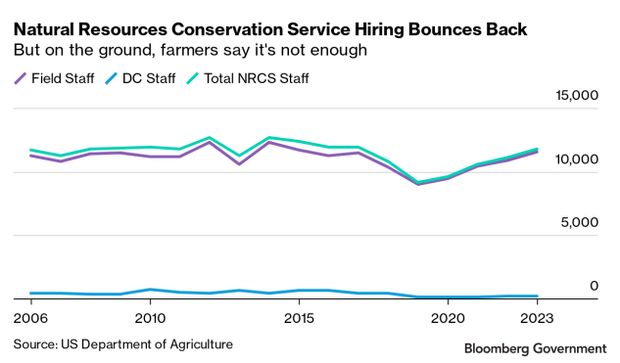

The number of NRCS workers has slightly rebounded after bottoming out in 2019, but conservation workers say it still isn’t enough. Its Washington, D.C., staff is half the size it was 15 years ago.

“A lot of people underestimate how many people you actually need,” said Molly Cheatum, Pennsylvania watershed restoration program manager at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

‘Breaking In’

Both the Conservation Service and the Farm Service Agency have offered in-person support for farmers since the 1930s, when their predecessors were created to relocate, subsidize, or assist farmers who had been battered by the Great Depression.

Some of the staff downsizing over the years was intentional. In 2012, as the country was still battling an economic downturn, the agriculture department closed more than 250 offices and facilities nationwide in a bid to cut $150 million from its budget.

Many of the current job openings are for soil conservation or county program technicians, local workers who process applications and help farmers access USDA programs. Vacancies are scattered across the country, with some starting salaries as low as $33,000, according to a department careers website. By contrast, the overall starting salary for college graduates is above $55,000 per year, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers.

Beyond processing loan paperwork and sharing information about available aid, technicians advise farmers on conservation practices, such as how to effectively plant cover crops to limit runoff. Without that help, a farmer’s conservation plan could take longer to implement—or, in a more severe case, they may be discouraged from applying in the first place.

Republican lawmakers on the House’s oversight panel last year told the administration that “countless” farmers had complained about local agency shortages, which also exacerbate delays in processing applications. “As our farmers progress through the planting season and into the harvesting season in the fall, it is important the FSA office is adequately staffed,” they wrote.

The problems are especially stark for novice farmers trying to absorb and navigate the scope of USDA programs, said Stu Lourey, government relations director at the Minnesota Farmers Union, a century-old nonprofit that represents 17,000 members.

“You’re trying to break into what can be a confusing system,” Lourey said. “That’s a unique challenge.”

The USDA acknowledged its staffing struggles and said it’s striving to increase nationwide recruiting and listen to the concerns of local beneficiaries.

In an emailed statement, a spokesperson said agency leaders continue “to work closely with state leadership to identify areas where additional staffing resources are needed in order to provide support through temporary staffing, overtime pay for current employees, and deploying staff from across the country through virtual and in-person means to assist with workload needs, when applicable.”

Farm Bill Fixes

The House and Senate agriculture committees have both begun holding hearings on a reauthorized farm bill, which, unless extended, must be passed by the end of September. The bulk of the bill’s cost covers the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program that provides foods for millions of low-income Americans.

Conservation will also emerge as a major focus in the 2023 reauthorization discussion. Democrats’ funding surge for “climate-smart” agriculture—which aims to limit pollution while enabling farmers to efficiently use their land—could clash with Republican opposition to specifically measuring conservation programs based on their climate impact.

Still, both parties largely agree these programs should be fully funded to help farmers conserve their resources.

The department has also started rolling out climate-focused agriculture funding to help farmers sequester carbon in their soil to make it healthier. That off-year funding, in addition to whatever conservation funding comes from the next farm bill, will provide a sizable pot for farm conservation.

Read More: Biden Climate Spending Inflames Conservation Debate on Farm Bill

The challenge is staffing.

“If there’s not the people there to work with farmers to institute it, no matter how much money you throw at it, it’s going to be difficult to distribute,” said Andrew Walmsley, senior director of government affairs at the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Leaders at the Farm Service Agency are reviewing changes that would help process farmers’ paperwork more quickly, a spokesperson said in a statement. The agency also cited improvements underway, like simplifying loan applications and using virtual tools to submit paperwork.

The staffing woes are an age-old issue that’s only gotten more complicated through the years as Congress passes beefier farm bills, said former Agriculture Secretary Dan Glickman. He said the USDA should focus more on how to modernize its technology, “because most farmers are very technologically competent.”

Closing and consolidating offices in less populous counties could be another way to promote efficiency, said Gibbs, a former county executive director for the FSA. This would cut down on salary and brick-and-mortar costs, but also make some farmers drive farther to reach a local office.

Forcing the Agriculture Department to make such choices could ignite a political battle in a divided Congress, Gibbs said. “A congressman or woman doesn’t want an administration of the other party to close a county USDA office in their county,” he said.

Even if lawmakers and agency officials agree to pour more money and effort into plugging the staffing shortage, advocates say finding and hiring the recruits will take time.

“The hiring process is kind of involved and so is the training process,” said Matt Kowalski, a watershed restoration scientist for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. “We can’t just snap our fingers.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Maeve Sheehey in Washington at msheehey@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com and John P. Martin at jmartin1@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.