FEC Eases Federal Contractors-Turned-Political Donors’ Path (1)

- Republicans rejected precedent on campaign giving

- GEO Group affiliates contributed $2 million to super PACs

(Adds campaign finance law detail in second to last paragraph; a previous update corrected Brett Kappel’s last name in 8th paragraph)

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The first $100,000 contribution to a pro-Donald Trump super PAC by an affiliate of the giant corrections company GEO Group came in August 2016, a day after the Obama administration announced it would end federal use of private prisons.

GEO’s stock price dropped by nearly 40% after the Obama announcement but shot back up when Trump was elected president and reversed Obama’s prison policy.

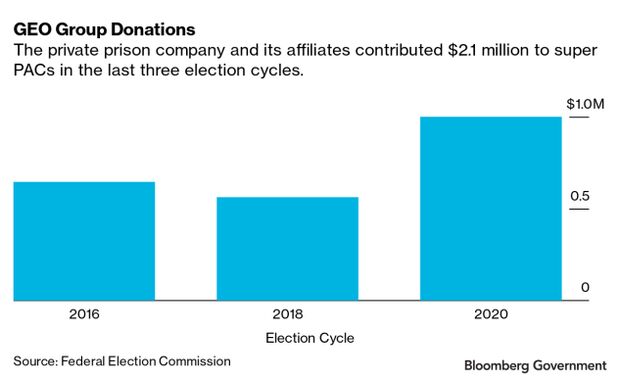

Since then, affiliates of GEO have contributed over $2 million to Republican super political action committees.

GEO’s contributions violated a decades-old ban on campaign money from government contractors, a watchdog group, the Campaign Legal Center, complained. The company, which operates prisons and detention centers for the Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, and state governments, has annual revenues of over $2 billion and has earned about $10.5 billion from federal contracts since its inception, according to a Bloomberg Government analysis.

But, in a move that could have a wide impact on other contractors, the Federal Election Commission announced in September it had dismissed the watchdog’s complaint against GEO on a 3-3 party-line vote. The FEC’s three Republican commissioners blocked staff-recommended enforcement action against a unit of GEO Group Inc., GEO Corrections Holdings.

GEO didn’t respond to emails requesting comment.

Road Map for Contractors?

The Republican commissioners rejected FEC precedent and said a company giving money to a super PAC doesn’t have to be “separate and distinct” from one having government contracts. Super PACs can take unlimited donations from corporations to support candidates but can’t give directly to a candidate’s campaign.

The FEC’s Oct. 20 statement provides “a road map for contractors to engage in direct political activity without liability for campaign finance violations,” said election lawyer Brett Kappel of the firm Harmon Curran.

Most contractors—like other big companies—are likely to remain reluctant to support candidates because they don’t want to appear partisan and fear backlash from customers, employees, or stockholders, Kappel said. But, “they’ll be asked” to give to super PACs after this ruling, he said.

It’s too early to know the full effect of the GEO ruling, other election lawyers said. The GOP commissioners didn’t strike down all limits on contractor contributions but simply rejected the analysis of FEC staff “in this case,” said Kenneth Gross of Skadden Arps.

FEC Republicans declared past precedents in contractor cases were “not supported by any general theories of corporate law or in our regulations,” said Craig Engle of Arent Fox.

Last Limits

Restrictions on federal contractors are one of the last limits left on corporate campaign money after the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. FEC struck down a century-old, general ban on direct spending by corporations to influence federal elections. The FEC maintained that limiting money from contractors, including contributions to super PACs, was still valid because it helped prevent undue influence in awarding contracts.

The Republican commissioners—Allen Dickerson, James “Trey” Trainor, and Sean Cooksey—said they dismissed enforcement action against GEO because there was no specific regulation governing contractor contributions to super PACs. Commission staff attorneys in the Office of General Counsel instead relied on prior FEC advisory opinions involving other contractors to recommend enforcement action.

“We reject this approach,” the commissioners said. Advisory opinions “can be used only as a shield by similarly situated respondents, not as a sword to be brandished by OGC in future matters.”

The statement means restrictions apply only to corporate entities that directly hold government contracts, said Dickerson, the FEC vice chairman.

“We’re not going to create a new rule of alter ego liability,” he said, adding that Congress could make such a rule if it wants.

Restrictions on contractors also are probably unconstitutional because super PACs aren’t formally linked to candidates, the commissioners’ statement added.

“We are skeptical of the Commission’s ability to identify a sufficient anticorruption interest in limiting government contractor contributions made to fund independent expenditures” by super PACs, they said.

Democratic commissioners agreed with a staff recommendation to pursue enforcement action against GEO, saying it was important to protect merit-based administration of government contracts, avoid pay-to-play, and ensure that government personnel involved in contracting decisions are free from political coercion.

“For over 80 years, federal contractors have been prohibited from making political contributions to prevent undue influence in awarding taxpayer-funded contracts,” FEC Democrats Shana Broussard and Ellen Weintraub said in a statement. Steven Walther, who holds a Democratic seat on FEC, voted with them but didn’t join the statement.

Chevron Matter Dismissed

In recent years, the FEC has assessed penalties against several contracting companies for contributing to super PACs. But in those cases, contractors said the violations were unintentional and agreed to settle.

In other cases, however, the FEC dismissed complaints by ruling that the corporate entity contributing to a super PAC had separate financing and control from the entity holding government contracts. A case involving Chevron Corp., the energy giant, was dismissed by a majority vote of the commissioners in 2014, without a full investigation, and Chevron has continued to contribute millions of dollars to super PACs aligned with congressional Republicans.

Lawyers for GEO said their client was treated differently. The FEC’s Office of General Counsel “simply accepted Chevron’s initial explanation” of its corporate structure, GEO attorney Jason Torchinsky told commissioners in a closed FEC hearing last April.

“OGC did not conduct three years of investigations or take any depositions,” as it did with GEO, said Torchinsky, of the firm Holtzman Vogel, according to a transcript provided to Bloomberg Government in response to a Freedom of Information Act request.

“If the Commission wants to present some kind of alter ego or veil-piercing theory” to establish GEO’s liability, Torchinsky said at the hearing, “it should do so in a regulation.”

Democratic commissioners tried in 2015 to clarify limits on contractors, but the move was blocked by Republicans, dying on a 3-3 commission vote.

Campaign finance law allows complainants to challenge the FEC’s dismissal of a complaint in court, but the Campaign Legal Center decided not to file suit in the GEO matter.

The GEO matter shows the commission itself needs to be overhauled, said Adav Noti, a former FEC staff attorney now with the Campaign Legal Center. “If wealthy special interests can use money to rig the system in their favor with impunity, why does the FEC even exist?” he asked.

To contact the reporter on this story: Kenneth P. Doyle in Washington at kdoyle@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergindustry.com; Kyle Trygstad at ktrygstad@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.