Gas-Tax Proxy Out of Reach as Clock Ticks for Highway Trust Fund

- Congress faces Sept. 2020 deadline to shore up highway fund

- Alternatives to gas tax aren’t ready to fill funding void

A long-discussed move away from gasoline taxes toward charging drivers by how much they use roads won’t be feasible in time to save Congress from having to make uncomfortable choices about how to pay for highway projects.

Congress faces a deadline for deciding how to pay for the next major infrastructure legislation of Sept. 30, 2020, when the current authorization expires and the Highway Trust Fund is projected to be insolvent. The gasoline and diesel taxes that fund the trust haven’t been raised since 1993 and are increasingly inadequate to support rising construction costs, as vehicles have become more fuel efficient and increasingly don’t use gasoline at all.

“The gas tax is what we have to rely on until we have a long-term fix, but it simply doesn’t meet our needs now and it won’t in the future. We need to stop putting this off,” Rep. Sam Graves (R-Mo.), the top Republican transportation leader in the House, said in an email. Graves wants to pursue a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) fee now, he said.

“We can fix the Trust Fund for the long-term with a VMT program,”Graves said. “Ultimately, if everyone comes together and pulls in the same direction, the long-term solution would come sooner.”

But beyond Graves, the idea of a vehicle-miles fee as a way to save the trust fund doesn’t generate much more enthusiasm than it did a decade ago, when then-Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood was pilloried by both Democrats and Republicans for merely suggesting it.

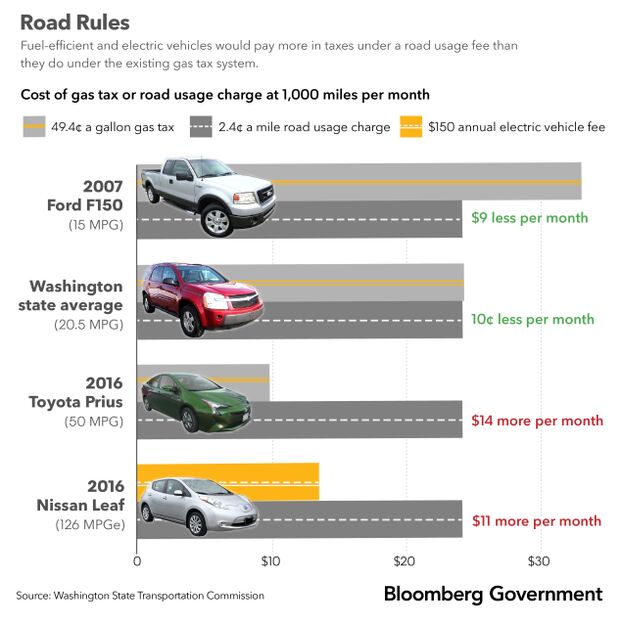

Concerns remain that a mileage-based system would allow the government to track the whereabouts and movements of motorists. A VMT also could reward users of gas-guzzling vehicles while weakening incentives to buy energy-efficient electric and hybrid cars. And people in the field who have tested systems for implementing road-user fees say the concept isn’t ready for national scale and that a forced rollout could cripple a promising policy and technology.

“We know from a technological standpoint all this can be done, but the politics and public acceptance issue are huge and very challenging,’” said Reema Griffith, executive director of the Washington State Transportation Commission, who has been discussing the VMT’s prospects with lawmakers. Washington completed its year-long pilot program on a road user charge in January.

Pay at the Pump

Graves and the previous top House Republican on transportation, former Rep. Bill Shuster, are most enthusiastic about a system that would pay the mileage fee through the pump, the way gasoline taxes are now collected. Smart technology in a phone or car, and in the pump, would communicate to calculate mileage fees and charge or deduct them from the fuel bill.

Shuster is now working for the lobbying firm Squire Patton Boggs on transportation and infrastructure issues. Before retiring, he proposed last July to raise the gas tax and then to eliminate it with a shift to VMT and other user fees by 2028.

Paying the road charge at a pump or electric charging station is better than an “inefficient” system where the federal government would have to collect fees from millions of drivers, Shuster said.

Right now, though, the technology for paying at the pump is furthest away among the various ways VMT could go national.

The only fully operational mileage fee system, in Oregon, doesn’t include any options that center on the gas pump. Oregon’s test of a pump-based system in 2006 was a “failure” and the state abandoned the idea, said Michelle Godfrey, education and outreach coordinator at the state’s Department of Transportation.

“It’s kind of like trying to thrust a modern day technology into a 1900s system,” she said.

Washington in January finished a year-long study, the largest per capita one to date, and also didn’t test pay-at-the-pump options.

The technology wasn’t advanced enough when Oregon did its study, but advancements since then prompted a pump-based pilot planned in the future in California, said Louis Neudorff, principal technologist with Jacobs Engineering Inc., which has developed and managed a number of state tests of mileage-based systems.

Neudorff said he’s has spoken with a range of vendors about how a pump-based system could operate but none have a solution that would make the process “truly seamless,” at least not yet.

In the Works

Washington began work on its pilot in 2012 and operated its 2,000 person, voluntary program from January 2018 through January 2019. It took several years just to develop the fees, using the average fuel economy of the fleet. It calculated the average gas tax per mile drivers pay to reach a 2.4 cent per mile charge that would apply to all vehicles under 10,000 pounds.

Both Washington and Oregon gave program participants choices of how to track and record their miles, including satellite-based radio-navigation tracking (GPS) and non-GPS options. The technology relied on a dongle plugged into a car’s OBD2 port, the one a mechanic uses to check a car’s computer system and that Progressive Insurance uses to measure customers’ driving habits. All new vehicles sold after 1996 are required to have the port.

The benefit of a GPS-based system is that it can help track miles driven out of state or on private roads, like a truck on a private farm. The location-based systems also include options of providing that data to a third party vendor or straight to the state. In Oregon there’s a restriction on how long the data can be kept (30 days) and how it can be accessed; police need a search warrant to gain access to the data.

Randal O’Toole, an employee with the libertarian think tank Cato Institute who lives in Oregon and participated in that state’s pilot, opted to pay Azuga, a private operator, to manage his GPS-based mileage fees.

“All the state knows is that it received a bunch of money from all the people who use Azuga. It doesn’t know how many miles I drove or where or when I drove them,” O’Toole said.

Other options include sending photos of the odometer to the pilot operator, or driving to a department of motor vehicles to have an employee log the vehicle’s miles.

“User choice is a pillar of this and it really doesn’t work any other way,” said Matt Chiller, Jacobs’ vice president federal government relations.

Political Headaches

One aspect of the mileage-based fee that appeals to some Republicans is that it would capture revenue from electric vehicles, which don’t pay into the Highway Trust Fund. Less fuel efficient vehicles end up paying less tax under a VMT system than they do with the gasoline tax. Energy-efficient vehicles would pay more.

Republicans such as the Senate’s top surface transportation authorizer, Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), have recently taken on electric vehicles, proposing an end to tax subsidies and adding new fees for them. Wyoming was the nation’s eighth-biggest crude oil producing state as of December, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration

“I believe the reason that some people now are coming up with this idea that VMT is the best solution is because they don’t want to raise the gas tax,” said LaHood, a longtime Republican House member who led the DOT under Democrat Barack Obama. “For conservative Republicans, it’s kind of a hangover from the tea party.”

Congress bailed out the highway trust with general taxpayer funds in 2015 rather than raise the fuel tax.

Even if lawmakers are warming to the idea of taxing by the mile, privacy concerns that were largely behind the furor over LaHood’s statements a decade ago remain, Shuster said.

“Sam Graves is a good friend of mine, I understand what he’s pushing for and I think it’s good he’s pushing in that direction, but I think there has to be a period of time,” Shuster said.

Washington and Oregon have the data to dispel myths that the government is tracking your moves via GPS, but the misconception is still there, Godfrey said.

Fuel Tax First

Top Democratic transportation authorizers in Congress such as House Transportation and Infrastructure Chairman Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) and Environment and Public Works ranking member Tom Carper (D-Del.) favor a fuel tax increase in the near term with an eye towards a road use fee in the future.

DeFazio has proposed a nationwide pilot program based on lessons learned from states since the last surface transportation bill passed in 2015.

“We’re not ready to jump to a vehicle miles traveled,” DeFazio told the tax-writing House Ways and Means Committee during a March 6 hearing. “But if we do a nationwide pilot in—in, you know, 10 or 12 years, we will be ready to move there.”

Shuster and DeFazio see privacy concerns melting away over time. There’s an entire generation that accepts that part of the convenience of wireless technology is that it tracks our movements, Shuster said.

Even if a VMT was ready for “prime time,’’ as Shuster put it, there are so many existing systems that rely on the gas tax and bond sales backed by those taxes that quitting cold turkey won’t work.

“It’s not like you can just unplug the gas tax,” Griffith said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Shaun Courtney in Washington at scourtney@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com