Foreign Cash at U.S. Colleges Pits Transparency Against Privacy

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

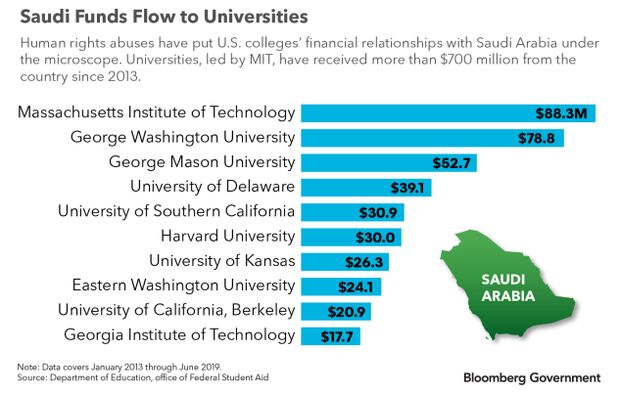

Massachusetts Institute of Technology officials, following the murder of U.S.-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi, in 2018, began an exhaustive review of the university’s financial ties to Saudi Arabia.

The university received about $7.2 million in Saudi funds in fiscal 2018 that supported computer simulation research into urban water management and climate change, and a fellowship program for Saudi women with doctorates in science and engineering to spend a year at the Cambridge campus, among several other initiatives.

Jamal Khashoggi’s Shift From Insider to Exiled Critic: QuickTake

MIT’s review, which ultimately recommended against cutting off the Saudi largesse, was unusually thorough. However, the Department of Education still found the university’s disclosure of foreign money wanting. This fall, it became one of six institutions the Trump administration has targeted with investigations for allegedly underreporting gifts or contracts with overseas entities.

More troubling for college groups than those investigations, the Education Department is looking to overhaul how it collects data on foreign funds from all higher education institutions in the U.S. In response to pressure from Congress, the department is introducing a new reporting regime that would require colleges to submit contracts for foreign gifts or business arrangements as well as the names of individual donors.

College groups warn the proposal goes well beyond what current federal law requires. Colleges say disclosing donor identities could have a “chilling effect” on new contributions despite promises of confidentiality from the department. And they say turning over full contracts would inundate federal officials with documents while doing little to improve transparency.

“If you’re looking for a needle in a haystack, it’s a bad idea to start by making the haystack bigger,” said Terry Hartle, senior vice president for governmental and public affairs at the American Council on Education.

The Trump administration, for its part, shows little patience for arguments that the rules are unclear. Department officials, in a letter to Senate lawmakers last month, said colleges had all the information they need to comply with the requirements.

Little Previous Scrutiny

Colleges and universities are required to report any gifts or contracts from foreign entities worth $250,000 or more under Section 117 of the Higher Education Act (Public Law 110-315). The provision was added in a 1986 reauthorization of the law.

Three decades ago, relatively few colleges received money from foreign governments or corporations. But in recent years the number of institutions with international footprints has expanded rapidly. Georgetown University and New York University, among others, have opened campuses in Gulf oil states such as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. And countries such as China have added support for language and cultural programs on U.S. campuses.

Enforcement of the Section 117 reporting requirements hasn’t kept up with that growth, according to an inquiry by the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. The panel released a report last year finding that the department had not tracked funding coming into U.S. colleges through Confucius Institutes, Chinese government-backed programs designed to promote the country’s language and culture.

“We want to have a constructive relationship with China,” Investigations Subcommittee Chairman Rob Portman (R-Ohio) said. “It’s got to be transparent. And it’s not too much to ask for schools to follow the law.”

After the report’s release and a hearing in which a senior Education Department official was taken to task over its findings, the department opened reviews of foreign funds at MIT and other universities, looking specifically into ties with China, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Russia.

MIT spokeswoman Kimberly Allen said the university is committed to working constructively with federal officials and reporting all information required by law but had no other comment.

The Education Department followed those investigations by revamping reporting requirements for foreign funds. InDecember, it sent a request for emergency review to the Office of Management and Budget for new standards that would govern how colleges report data on foreign funds. Department officials are seeking approval of those changes by the end of January, when colleges must submit new data on foreign funds.

“Section 117 has been on the books for 40 years, and the department has never acted on it. There is a bipartisan consensus that the Department under prior Administrations dropped the ball,” said Reed Rubinstein, acting general counsel at the Education Department. So, under Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’s leadership, “we’ve moved to do what Congress has required,” he said.

`Uncharted Territory’

College groups have questioned the wisdom of more stringent reporting of foreign funds, citing concerns for the privacy of business partners and donors. They’ve vented in letters to the Education Department and the Senate Homeland Security Committee that the Trump administration has largely refused to clarify what’s expected of institutions either under current requirements or those the department is looking to add.

“The Education Department has been noticeably unwilling to engage in a constructive dialogue about how to improve compliance with Section 117,” said the American Council on Education’s Hartle. “They have consistently refused to meet and they won’t answer questions from individual institutions.”

That’s a departure from the Trump administration’s approach to regulation of student loans, college accreditation, and Title IX, Hartle said.

Groups such as the American Council on Education say the Education Department should pursue rulemaking that would include more formal requirements for public input rather than introducing data-collection standards through a less-stringent update to the Paperwork Reduction Act. The department last issued guidance to colleges in 2004.

“It’s a totally new accounting system colleges will have to comply with,” said Deborah Altenburg, assistant vice president for research advocacy and policy at the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities. “It’s uncharted territory.”

Legislative Response Expected

The Trump administration says the obligations of institutions are already clear. Colleges already have tools in place to track foreign funds effectively, Education Department officials told Portman’s subcommittee, citing preliminary findings from the Education Department’s investigations opened in 2019. Institutions have systems able to track individual contributions of $100 or less, the officials told lawmakers.

“This is one of the least-complicated compliance regimes out there,” Rubinstein said. “Many schools keep detailed data even on small-dollar donors, so it’s absurd to say that it’s burdensome for them to track their large-dollar donors.”

Some government transparency advocates, though, say there is still room for more explanation from the Education Department and that it may be overstepping its authority under the Higher Education Act.

“They should go to Congress and make the case that they need this information,” said Mandy Smithberger, director of the Straus Military Reform Project at the Project on Government Oversight.

Portman’s subcommittee has legislation in the works for early 2020 that would update standards for reporting foreign money in part by lowering the current $250,000 thresholdso that even more gifts or contracts would have to be disclosed. New legislation is still needed even after the Education Department announced plans to overhaul its reporting requirements for schools, he said.

“The schools—they actually would prefer our approach, the legislative approach, because we think it will be easier to comply with what we’re laying out,” he said. “It’s not meant to make things administratively difficult or create burdens. It’s meant to just get the information so we know what’s going on.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Andrew Kreighbaum at akreighbaum@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergtax.com; Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.