Five Things to Know About Long Shot Push for 585-Member US House

- Blumenauer bill would raise 435-seat House cap

- 150 more members means more office space and electoral votes

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

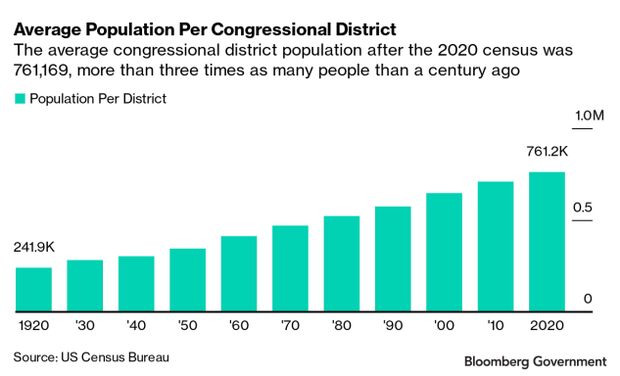

The size of the House of Representatives has been at 435 members since Woodrow Wilson was president more than a century ago, even though the US population has since more than tripled.

But Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) is trying to jump-start the idea of expanding the chamber. He recently introduced a bill (H.R. 622) that would expand the House to 585 members after the 2030 census, with small increases in subsequent decades.

“Not only would it make it easier to represent folks, it would be easier for people in the states to know who their congresspeople are and to be able to have access to them,” Blumenauer said in an interview.

With more than 331 million people as of the 2020 census, there are more than 761,000 people per House member — a ratio much higher than in other industrialized countries.

The bill remains a long shot, especially with Congress divided and many lawmakers weary of an expansion that could dilute their power.

BGOV Cheat Sheet: Increasing the Size of the U.S. House

Still, history shows the idea is not new. The size of the House membership has been debated since the founding of the republic and momentum for an expansion has ebbed and flowed over the nation’s history.

The Constitution in 1787 set the House at 65 members until the first census in 1790, when representation became based on population. Every state is entitled to at least one House member, and the size of the chamber can’t exceed one per 30,000 people — or a maximum of about 11,000 House members under the 2020 census population.

In nearly every decade until 1920, as the population and the number of states admitted to the union increased, so too did the size of the House — a move that protected the seats of incumbents and ensured no state would lose seats.

A 1911 law increased the size of the House to 433, effective with the 63rd Congress starting in March 1913, with a provision to add one district each for Arizona and New Mexico after they achieved statehood in 1912, for a total of 435.

“If we don’t do something, then the size of the districts are just going to be completely unmanageable,” Blumenauer said.

Here are five things to know about the legislation.

Fewer constituents

As districts become more and more populous, it’s harder for House members and their staff to respond to communications from constituents or help them navigate the federal bureaucracy to resolve issues like Social Security payments, veterans’ benefits, or immigration status.

Blumenauer, a House member since 1996, said the strain on House members was exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic because more people contacted their representatives for assistance from the federal government.

More office space

A much bigger House probably would require another office building and maybe an expanded House chamber. Blumenauer’s bill would direct the Architect of the Capitol, in consultation with the Administrator of the General Services Administration and other officials as needed, to “conduct a study of the facility needs and other logistical issues” involved in substantially increasing the House membership.

The three main House office buildings — Cannon (completed in 1908), Longworth (1933), and Rayburn (1965) — “are not particularly efficient in terms of energy, in terms of space,” Blumenauer said.

A larger House would also spark discussion about committee and subcommittee sizes.

A larger electoral college

Because a state’s presidential electoral votes is the sum of its two senators and its House members, Blumenauer’s bill would increase the total number of electoral votes and how they’re distributed among the states.

There would be 688 electoral votes at stake in the 2032, 2036, and 2040 presidential elections, up from 538 now. A winner would need 345 electoral votes to win, up from 270 now.

A huge 2033 House freshman class

Adding 150 districts after the 2030 census would produce an unprecedented number of new districts for the political parties and candidates to contest in the 2032 election — and a huge contingent of new members in January 2033. The measure could dilute some of the institutional advantages current incumbents enjoy.

“Larger and larger districts are more difficult to campaign in. They’re more expensive. It’s harder for a new person to be able to challenge an incumbent,” Blumenauer said.

An “out of the box” idea

A December 2022 report from the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress didn’t incorporate the expansion of the House among its final recommendations for improving how Congress works, though the panel held a hearing in July 2022 that included it among “innovative” and “out of the box” ideas.

“It’s going to take probably one or two sessions of Congress for it to be able to get the momentum that it needs and to be able to prepare for it,” Blumenauer said. “But I think it’s an conversation that’s long overdue, and I am impressed with how receptive people are to this approach.”

With assistance from Loren Duggan

To contact the reporter on this story: Greg Giroux in Washington at ggiroux@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: George Cahlink at gcahlink@bloombergindustry.com; Bennett Roth at broth@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.