Fights Over Money, Ships, and Planes Set to Lead Defense Debates

- Congress to consider defense spending, authorization bills

- Consensus grows to back funding for second Navy destroyer

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Congressional Democrats and Republicans will spar over the size of President Joe Biden’s proposed $715 billion Pentagon budget, even as there’s one thing both parties can agree on: his fiscal 2022 request is unsatisfactory.

Lawmakers will confront new hurdles as they consider the defense authorization and spending bills for next year in July. The president’s request to Congress was the latest-ever when it arrived May 28, leaving less time than usual to debate what is considered must-pass legislation. It also omitted multiyear planning— known as future years defense programs—usually presented in the annual request to forecast what funding, manpower, and force structure the Pentagon needs over a five-year period.

The absence of future projections makes the request hard to digest, lawmakers said, especially because there’s little justification for the decisions to retire ships and aircraft across the military services.

“This budget is very handicapped because of the delay and also the absence of” future projections, Rep. Joe Courtney (D-Conn.), a senior member of the House Armed Services Committee, said in an interview. “The issues are endless right now. So far it seems like it is a recurring theme trying to rationalize the ‘divest-to invest,’” in order to focus on strategic competition with China, he said. The proposed budget also presents “an awful lot of shrinkage at the same time. It’s going to be a struggle,” Courtney added.

The Air Force, for example, is proposing to retire 201 older aircraft and buy 91 new ones. The requested divestments “are not matched with equal procurement of new capabilities,” said Adam Smith (D-Wash.), the House Armed Services Committee chair.

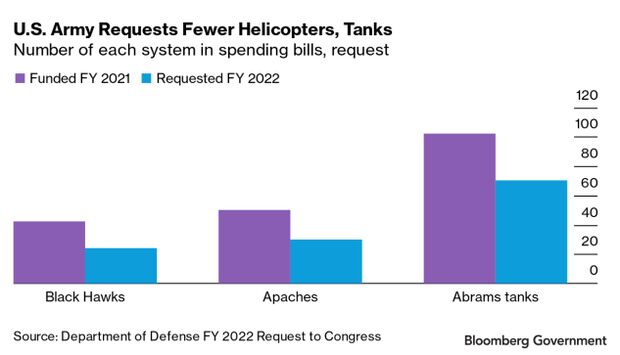

The Army is also planning on buying fewer Chinook, Black Hawk, and Apache helicopters, and Abrams tanks. The Navy, meanwhile, proposes buying eight ships, only four of which are combat vessels and the other four support ships. More importantly for Congress, a second DDG-51 destroyer is missing from the Navy’s request. Congress has typically appropriated more funds for some military hardware than the Pentagon requests in order to maintain a large defense industrial base with skilled workers.

Pentagon Chief Defends $715 Billion Budget Aimed at China

Here are some of the key issues that Congress will have to confront:

Topline

Biden proposed nudging the budget up 1.6% compared with this fiscal year, which would amount to about a 0.4% decrease in real terms adjusted for inflation. Congressional Republicans make it no secret that they want to see a larger defense budget, matching a 3% to 5% yearly increase.

Sen. Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma, the top Republican on the Senate Armed Services Committee, and top GOP appropriator Richard Shelby of Alabama, already tried to get support for a larger defense budget by trying to require “parity” in defense and nondefense increases. The Senate rejected, 44-53, an amendment they offered to a bill (S. 1260) to boost competitiveness with China.

Meanwhile, Rep. Ken Calvertof California, the top Republican on the House Appropriations Defense Subcommittee, told Bloomberg Government that he too will seek an increase to about $740 billion. The political math to pass defense bills in the House is complicated. Democrats need Republicans to back any defense legislation as dozens of progressive Democrats tend to vote against higher military spending.

Pentagon Seeks to Boost Tech Edge Versus China in Budget

The Senate is likely to boost the topline number, said Todd Harrison, director of defense budget analysis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“They will have to get some sort of bipartisan agreement,” Harrison said. “There is going to be a lot of debate about the topline number, but ultimately what it boils down to, if Congress wants to prevent some of these retirements and if they want to add back the procurement, then Congress will have to look at that topline and perhaps add $10 billion or $15 billion to the defense budget,” he said.

Among Republicans, there is “as close to consensus” as possible on a higher defense budget, said Mackenzie Eaglen, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Both parties also increasingly agree: the Pentagon will start its next fiscal year on Oct. 1 under a stopgap spending measure because Congress won’t have time to write and negotiate differences on the appropriations bills.

Navy Arleigh Burke Destroyer

The absence of the second Navy destroyer from the 2022 budget request is perhaps the largest single item that Congress will try to overwrite. The Navy included the second destroyer, made by General Dynamics Corp. and Huntington Ingalls Industries Inc., on its wish list it sent to Congress after the official budget request. Austin told senators last week that the Pentagon plans to “resource” the second DDG-51 in fiscal 2023.

Boeing Jets, Navy Destroyer on U.S. Military’s $17.2b Wish Lists

“DDGs are the workhorse of the Navy,” said Susan Collins(R-Maine). General Dynamics builds the ships in her home state and has hired about 3,000 shipbuilders since 2018. “We need more DDG patrolling the Pacific, not fewer,” she told Austin during a Senate Appropriations Committee hearing last week.

“There isn’t a single person happy with the Biden Navy budget: it is dismal, it is anemic,” AEI’s Eaglen said. “There was hope there would be more meat on that bone this year.”

Chinook Helicopters

The U.S. Army left out Boeing Co.’s upgraded Chinooks from its official fiscal 2022 budget request, though service leaders included money in their wish list sent to Congress.

For two years in a row, the congressional defense committees rejected U.S. Army plans to curtail its Boeing Chinook CH-47 Block II program—an upgraded standard model of the workhorse helicopter used for transporting troops, supplies, and artillery to the battlefield.

The company benefits from the backing of a bipartisan group of lawmakers from Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey, where the Chinooks are built or where most workers on them live. A Chinook manufacturing facility employs more than 4,400 people in southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey, Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon (D-Pa.) told the House Armed Services Committee last month. The comments suggest the helicopters are another area of proposed cuts lawmakers may reverse.

Army Defers Boeing Chinooks in Budget Until Later Wish List

The Army also plans to reduce purchases within its aviation portfolio, including Boeing’s Apaches and Sikorsky Black Hawks, Army officials said. Sikorsky is a subsidiary of Lockheed Martin Corp.

Joint Strike Fighter

Smith, the House Armed Services Committee chair, earlier this year telegraphed what is likely to be one of the toughest money fights in Congress this year: over the F-35. Over the last decade, lawmakers have consistently spent more money on the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter aircraft than the Pentagon asked for, enticed by its next-generation technology and the promise of well-paying defense jobs in their districts.

Smith is looking into alternatives—potentially a mix of aircraft and other technologies such as drones—as well as the possibility of buying an alternative engine, he said. The Pentagon canceled a secondary engine program for the F-35 a decade ago.

Lawmakers now are focusing on the future challenges of the multiservice, multinational stealth fighter aircraft: the prohibitive cost of flying the planes, and the cost of maintaining and sustaining them—especially at the peak of their operational life.

F-35 Boon at Risk as Democrats Protest Extra Jets for Lockheed

Boeing Tanker

The congressional defense committees likely will look at ways to influence progress for the troubled KC-46A midair refueling tanker aircraft from Boeing.

One of the most outspoken critics of the program, Rep. Rob Wittman (R-Va.), said earlier this month that the U.S. Air Force signed “a bad contract” with Boeing for the tanker and should actively manage the contract or recompete the program.

“To date, the KC-46A has problems holding the fuel it has, delivering fuel it provides, and in some cases, has the potential to severely damage receiving aircraft. It even has problems being able to hold the sewage from onboard passengers,” he said.

Top Lawmakers Hit Air Force on ‘Bad Contract’ for Boeing Tanker

Due to delays, the tanker won’t be fully functional until 2024, Wittman said. In part because of the trouble with the KC-46A and because tankers are key assets for the military, Congress may also reverse the decision to retire older tankers such at the KC-10 and KC-135, Eaglen, from the American Enterprise Institute, said.

War Authorizations

The House voted 268-161 last week for a bill (H.R. 256) to repeal the 2002 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (Public Law 107-243) that served as the legal justification for the war in Iraq. The Senate will likely follow suit later this year, as Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) said he backs the repeal.

The Biden administration also backs Congress scrapping the law but has said it wants to work on a replacement. An updated authorization—which could also cover the authorization (Public Law 107-40) enacted after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attack—may reverberate into the defense bills, complicating the legislation.

“Will the entire Congress be able to rewrite something in its place that is slimmed down?” Eaglen said. “You could foresee language in the authorization bill prohibiting certain actions until a new one is in place. That is definitely a big issue looming over foreign and defense policy.”

Sexual Assault

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) has momentum to remove decisions on prosecuting sexual assault cases from the military’s chain of command. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, Gen. Mark Milley—the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff—and Jack Reed (D-R.I.), the Senate Armed Services chairman, have all hinted that they would support such a change to the Uniformed Code of Justice.

But there is a snag: Gillibrand’s bill (S. 1520), which has 65 bipartisan cosponsors, touches on all major crimes, not just those of sexual assault and harassment. Both Austin and Milley said that would be too big an overhaul to the military’s justice system. Gillibrand has tried to bring her legislation to a vote in the Senate only for Reed to block her multiple times, saying the legislation is in his committee’s purview.

Civilian and military leaders see action on sexual assault as inevitable, and now they want to shape it to limit the damage, Eaglen said. Even so, the change will happen, which is “pretty remarkable,” she said. The military and high-level lawmakers have resisted the changes for years, even as sexual assault incidents have gone up.

Budgeting Process

Overall, lawmakers are increasingly miffed at the Pentagon’s “Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution” process, which allocates resources for weapons systems, equipment, force structure, and other programs. The annual process serves as the framework for the Defense Department’s leaders to decide funding for programs and force structure requirements based on strategic objectives, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Aspects of the process, which started in the early 1960s, can change based on current events or leadership preferences. But it generally takes at least two years to add funding for new projects.

Harrison, from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said the concern is that the current system’s lack of speed prevents the U.S. from being agile enough to compete with adversaries such as China and Russia.

Others say the approach is outdated. “It was a model that was appropriate for the industrial age, but we’re in a post-industrial age,” Reed said of the process.

To contact the reporter on this story: Roxana Tiron in Washington at rtiron@bgov.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.