FEMA Stretched Beyond Climate Response as Disasters Balloon

- FEMA tasks have inflated since its Cold War-era roots

- Former leaders, lawmakers seek bureaucratic, workforce changes

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Atmospheric rivers drenched California and deadly storms crept toward Mississippi as Deanne Criswell sat in her corner office in Washington, D.C., and tackled a loaded question: Is it all too much for FEMA?

Federal Emergency Management Agency workers form the government’s rapid-response team for natural disasters while juggling disparate tasks that now range from distributing vaccines to aiding migrant children at the border.

“Yeah, there’s a lot, right?” the FEMA administrator said in an interview. But she insisted the agency can meet the moment. “The role of the emergency manager really is the role of problem-solver.”

Former agency leaders, disaster specialists, and lawmakers are not all so confident. As demands snowball, some see an agency hobbled by bureaucracy and an overstretched workforce.

And climate-fueled crises keep mounting before the agency can close the book on recovery from the last disaster.

“The concern is that they are being asked to do more and more and more without being given additional staffing, additional resources, or additional authorities to do it,” said Chris Currie, a director on the Government Accountability Office’s Homeland Security and Justice team.

Climate Test

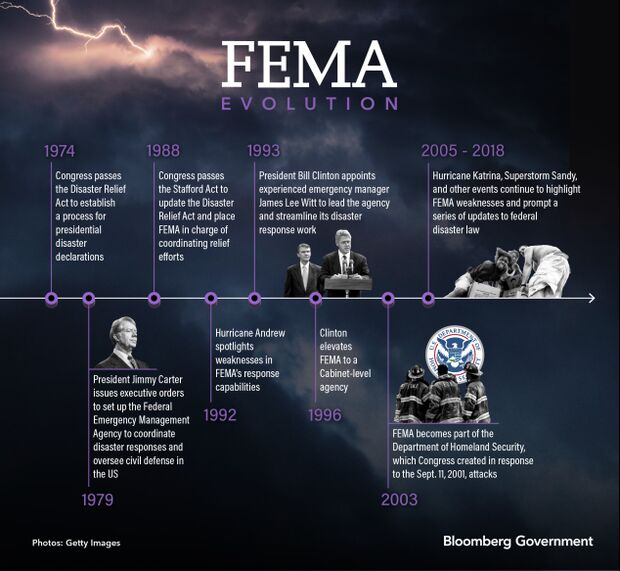

Today’s FEMA looks little like the agency created in 1979, when President Jimmy Carter sought to streamline federal disaster relief and coordinate civil defense as the Cold War dragged on.

Congress almost immediately began adding to the agency’s plate, starting with preparing for earthquakes, providing emergency food and shelter, and ensuring dam safety. And it hasn’t really stopped. During the pandemic, FEMA workers set up mass vaccination sites and even provided funeral assistance to the families of Covid victims.

But nothing is testing FEMA like climate change.

According to a 1993 watchdog report, the agency expected one to two “catastrophic disasters requiring life-sustaining services from the federal government” each year. But in the first half of this year alone, FEMA logged 35 major disaster declarations across the country.

While climate science stresses planning in anticipation of stronger and more dangerous weather events, FEMA must function in a government that has at times been reluctant to even acknowledge climate change.

That disconnect and the stresses of working disaster response take a toll. FEMA had a 35% staffing gap across its disaster workforce at the start of fiscal 2022 due to employee burnout and attrition, according to a May GAO report. And the Department of Homeland Security, which now houses FEMA, consistently ranks among the worst in government in employee morale surveys.

“They’re bringing people in, but they’re losing people at the same time,” GAO’s Currie said. “Some of their part-time, temporary workers maybe go off to other work. It’s a constant challenge for them to be fulfilled with the right people, with the right qualifications.”

Katrina and Sandy

FEMA’s authorities rest primarily within the 1988 Stafford Act, but Congress expanded the agency’s flexibilities by enacting critical laws after two particularly deadly and expensive disasters: Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

Katrina exposed FEMA’s inability to hit the ground running after disaster with robust, life-saving response and recovery. The agency provided short-term trailer housing for victims that ended up lasting for years, exposing them to toxic levels of formaldehyde. FEMA’s post-Katrina failures also highlighted the muddled lines of the agency’s authority within the then-fledgling Department of Homeland Security, and its constraints under the law.

After Sandy, it became clear that FEMA needed to deliver aid faster to victims, who continued to struggle with an onerous and bureaucratic relief process.

The 2006 Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act and the 2013 Sandy Recovery Improvement Act defined the agency’s mission more precisely, elevated its role in coordinating emergency management efforts across the federal government, and improved how it serves survivors.

With its new authorities, FEMA was able to fully embrace its role of crisis coordinator within the federal family, said President Barack Obama’s FEMA administrator, Craig Fugate. The agency under his leadership supported the US Agency for International Development after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the Department of Health and Human Services during the 2009 H1N1 swine flu outbreak in the US, and the Defense Department during the 2014 crisis of unaccompanied immigrant children at the US border.

“Everyone keeps talking about the disaster defining this, but it’s really the process,” Fugate said. “When the org chart of government can’t meet the needs, that’s a good time to look to emergency management.”

Currie, who has spent years investigating DHS agencies and programs, said FEMA workers are natural fits for the assorted missions. As emergency managers, they’re trained in communication, coordination, leadership, and marshaling resources. “They’re able to handle these big, complicated situations,” he said.

Listen to Kellie Lunney and Ellen M. Gilmer talk about their story on our podcast, On The Merits

But workers are emotionally drained by the crisis situations they encounter on the job, said Steve Reaves, president of the American Federation of Government Employees Local 4060, which represents FEMA employees.

“We’re the closest thing in the federal government to the Red Cross,” he said. “We never want to let the American public down.”

Climate Resilience

Responding to today’s urgent need isn’t FEMA’s only job. Alice Hill, an Obama-era White House resilience official now at the Council on Foreign Relations, said FEMA “needs a workforce that understands resilience, and particularly as it applies to climate change.”

“Because if you just do resilience and don’t also include active consideration of future risk, you may find yourself not very resilient,” Hill said.

Criswell agrees that the resilience side of FEMA’s mission—preparing communities to withstand more frequent and more severe weather—has to be “pulled out from the shadows of response and recovery.” FEMA’s own mission statement is to help people “before, during, and after disasters.”

“We have to start showing how communities have done better when they have invested in mitigation,” said Criswell.

The Trump administration launched a grant program to help communities prioritize resilience and mitigation projects, and Criswell later elevated it.

But disaster relief may need to carry more conditions on resilience and managed retreat to ensure recovery efforts actually help communities avoid future problems, said Juliette Kayyem, an Obama-era DHS official and former Massachusetts homeland security adviser.

“These communities rebuild in ways they’re likely to suffer harm again,” she said. “It’s this ridiculous cycle.”

Viral video of the Atlantic Ocean swallowing a home on North Carolina’s Outer Banks shows how beach nourishment projects and other bulwarks against an encroaching shoreline can’t stave off Mother Nature forever, even in affluent places and even during typical weather.

Poor communities are at even greater risk because they lack resources, and FEMA has faced criticism for failing to help underserved areas access federal aid—though Criswell has worked to rectify those inequities in disaster response.

Solutions may be bigger than FEMA. Emergency managers say state and local agencies need resources to ramp up their capacity. Hill also recommended a comprehensive national climate adaptation plan that involves multiple federal agencies to help level the playing field when it comes to disbursing money where it’s needed most.

“Right now, we have no way to prioritize among resilience investment across agencies,” Hill said. “It’s like spreading a thin layer of peanut butter across a piece of toast and expecting that’s going to protect us.”

Flood Insurance Fights

One challenge in planning for disaster is that public officials don’t like telling constituents where to live, which complicates FEMA’s role in administering the National Flood Insurance Program.

FEMA’s national flood maps haven’t been updated to reflect the changing climate and risk. Yet they still determine if a property is required to purchase flood insurance. More than 40% of NFIP claims come from outside high-risk flood zones, according to FEMA.

FEMA took one step by rolling out a new pricing system in 2021 based on more accurate risk assessments for NFIP premiums, known as Risk Rating 2.0.

The new ratings, which account for flooding and distance from water for individual properties rather than broader flood zones, meant more than three-quarters of policyholders saw higher premiums, the Congressional Research Service reports, with rate increases ranging from $120 to $240 a year. Constituents have complained, and lawmakers from both sides of the aisle want to modify the program.

“This is something we are going to have to come in and legislate on,” Rep. Garret Graves (R-La.) said in an interview this spring, calling the premium spike “a disaster” for some Louisiana policyholders. Several House and Senate Republicans and Democrats in June introduced legislation to overhaul NFIP, including changes to Risk Rating 2.0.

Congress last tried to better align premium rates with actual flood risks in 2012 (Public Law 112-141) but quickly delayed the increase in 2014 (Public Law 113-89) when constituents complained.

Read More: Climate Change Puts US Flood Insurance Program Deeper Into Debt

Criswell and David Maurstad, who leads the National Flood Insurance Program, have urged Congress to respond to the complaints this time by creating a “means-tested” affordability program within the NFIP, and link subsidies to a policyholder’s ability to pay.

‘Nobody Notices’

Congress is also being urged to think more proactively about FEMA’s overall funding and structure.

The randomness of catastrophic disasters makes FEMA’s budget needs among the government’s most unpredictable. While the agency spends on average $12 billion a year through its Disaster Relief Fund, the amount varies widely depending on real-world events. It has ranged from $2 billion in 1992 to $47 billion in 2020, in 2022 dollars.

Lawmakers use annual funding bills to add to the account most years, but also repeatedly scramble to approve supplemental funding when specific disasters hit with more devastation than planned for.

From 1992 through 2021, budget authority appropriated to the Disaster Relief Fund totaled $469 billion, in 2022 dollars, the Congressional Budget Office reported. And “nearly three-quarters of that amount was provided through supplemental appropriations,” the office said.

Some emergency managers say Congress needs to take a more comprehensive look at the agency’s authorities and capacity and try to get ahead of the next pressure points.

“FEMA is gonna get criticism no matter what happens, that just goes with the territory,” Fugate said. “But this goes back to Congress. Congress passes the laws, they authorize agencies to do stuff, they appropriate funds to do that.”

Because FEMA has avoided large-scale, Katrina-style missteps lately, it’s tougher to get lawmakers’ attention for staffing or resource needs, said Richard Serino, an Obama-era deputy administrator now at Harvard University.

“When they do a good job and things are going well, and you need more money to do a good job, nobody notices,” he said.

But lawmakers are quick to use FEMA as a political punching bag. In February, House Judiciary Committee Republicans complained that FEMA provided grant funding for migrant care in Washington, D.C., but didn’t make federal relief money available after the Norfolk Southern train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio.

But FEMA already was on the ground in Ohio, coordinating logistics and helping the lead agencies—the Environmental Protection Agency and the Transportation Department—respond to the crisis. The incident didn’t meet the criteria for a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act, and so FEMA wasn’t authorized to do more.

“It would be nice if Congress read their own laws,” Fugate said.

Catch-All Agency

FEMA has devoted resources in recent years to leading the resettlement of Afghans in the US, navigating the pandemic, and helping manage unaccompanied children at the border. “We’ve become the default 911 for the country,” Reaves said.

FEMA’s workforce of around 23,000 people—a mix of permanent, full-time employees, and temporary workers deployed to disasters—has grown by close to three times the roughly 8,000 workers it had 20 years ago when it became part of DHS. But it’s still falling short of disaster staffing targets, and reported discrimination and harassment in the workplace haven’t helped, GAO says.

“The question for me is not necessarily what FEMA is involved in responding to,” said Samantha Montano, a disaster researcher and emergency management professor at Massachusetts Maritime Academy, “but whether or not they have the capacity to respond to those issues.”

Criswell, the first woman to run FEMA, said she’s invested in the agency’s role as an evangelist for emergency management throughout the country, helping to elevate the role of first responders particularly at the state and local levels.

“We’re getting asked to do things we’ve never been asked to do before and that are not part of a disaster response, and I want to be able to help our state and local emergency managers do the same thing,” she said in an interview this spring.

“In my perfect world, in 10 years, FEMA is really able to help build the profession as a whole,” she added, “and build the understanding of what emergency managers do, and why they are so important.”

‘Shotgun Wedding’

President Bill Clinton bumped up FEMA’s status to Cabinet-level in 1996 to give it a more direct line to the White House and a higher profile among agencies. But its seat at the table changed when FEMA was subsumed by the Department of Homeland Security, the behemoth agency cobbled together in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

Hill described DHS’s creation as a “shotgun wedding.” FEMA still has a direct line to the White House when it comes to disasters, but its everyday operations are subject to the bureaucracy and politics of DHS, and congressional oversight is splintered among competing committees.

Some emergency managers believe an overhaul of FEMA’s position within the executive branch would help address concerns about its workforce and day-to-day operations.

“There is pretty broad consensus among folks in emergency management, both researchers and practitioners, that FEMA will not be able to be effective to the extent that we need it to be while it is still under the jurisdiction of DHS,” Montano said.

GAO’s Currie urged caution, noting that reorganizations are often messier than they’re worth. “There’s often secondary effects of that, and it’s not the magic bullet that everyone thinks it’s going to be,” he said.

Lawmakers tried and failed to move FEMA out of DHS more than a decade ago, and freshman Rep. Jared Moskowitz (D-Fla.), a former state emergency management official, has pledged to revive the effort.

Criswell laughed when asked about the latest push. She acknowledged “pros and cons” to FEMA being housed in DHS but said she would “let the rest of the world figure out where they want to go with it.”

Four days later, she was on the ground in Mississippi, where the brewing March storm turned into a series of devastating tornadoes. It was the 16th major disaster declaration of the year.

To contact the reporters on this story: Kellie Lunney in Washington at klunney@bloombergindustry.com; Ellen M. Gilmer in Washington at egilmer@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com; Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.