Facebook, Google Monopoly Fears Prompt House Antitrust Scrutiny

- Cicilline cites need to revisit law from era of oil barons

- Republicans caution against using statute to bust big tech

Widespread frustration with the economic power social media giants Facebook and Google wield is spurring the first top-to-bottom review of antitrust law by Congress in 70 years.

A House Judiciary subcommittee is studying the digital market’s “absence of competition’’ to determine “how did it get to this place,” the panel’s chairman, David Cicilline (D-R.I.), told reporters. Antitrust laws were mostly written “during the railroad monopolies and in the time of the oil barons,” he said. “It’s a different economy now.’’

The first face-off over antitrust between Congress and the big-tech companies is set for July 16. That’s when executives for Facebook, Google and an Amazon in-house lawyer are scheduled to testify before Cicilline’s panel. Maureen Ohlhausen, a former Republican acting chairwoman of the Federal Trade Commission, is also set to appear, Bloomberg News reported.

“We’re always happy to answer questions about our business,’’ said Google spokeswoman Julie Tarallo about the hearings.

Facebook representatives didn’t respond to emails and a call seeking comment.

House investigation of market domination by big tech is likely to set off a broader debate about whether Congress should enact new rules for digital-age companies and give government antitrust enforcers additional tools to stop anti-competitive behavior.

The probe comes during an open season on big tech bashing that’s partly fueled by public outrage over Facebook Inc.‘s failure to protect users’ personal data. The company predicts that breach could cost $5 billion under a settlement being negotiated with federal regulators.

The Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission signaled plans to probe whether market dominance of the two social media companies, as well as Apple Inc.and Amazon.com Inc., suppresses competition.

Political Bias

President Donald Trump has weighed in, too, accusing Google and Facebook of political bias against conservatives and calling for the government to sue the two social platforms for unspecified wrongdoing.

Some Democratic presidential candidates, notably Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), favor breaking up big tech companies such as Facebook and Google’s Alphabet Inc.

House Republicans, though supportive of the hearings, were cautious about their ultimate goal and warned against a rush to break up big tech companies.

Did Big Tech Get Too Big? U.S. Joins Europe in Asking: QuickTake

The Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law Subcommittee hearings may not generate political consensus to enact antitrust legislation, such as those that led in 1950 to passage of the last major changes to competition law. But they could send a political signal that emboldens government antitrust enforcers to be more aggressive.

Warren and Cicilline “want a stronger appetite for risk at the enforcement agencies’’ and are, in effect, saying “`we want you to be more aggressive even if you lose more cases,’” said William Kovacic, a former Republican FTC chairman.

Lobbying Up

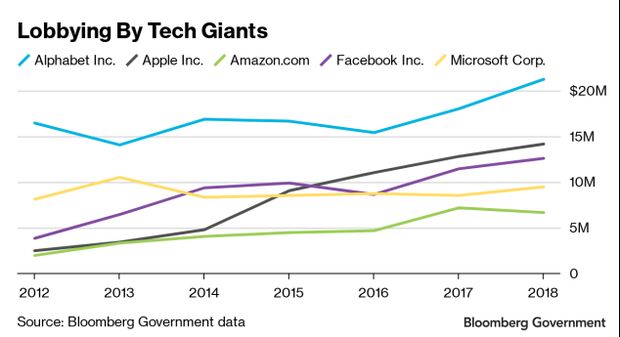

“These cases are not just fought in court, there is a huge lobbying effort now being ramped up by the major platforms,’’ said Harry First, a New York University law professor who headed antitrust enforcement for the New York’s attorney general during the landmark case against Microsoft Corp. two decades ago. “If you are really going to go after these powerful companies, there ought to be political support and the government is going to need it.”

Facebook’s Washington lobbying expenditures more than tripled to $12.6 million last year from $3.9 million in 2012, according to Bloomberg Government data collected from public registration records. Google’s parent, Alphabet, spent $21.2 million on lobbying in 2018, up 29% from $16.5 million in 2012.

Google, Facebook, Amazon Spent Record Amounts on Lobbying

Congress has largely stayed on the sidelines of antitrust since enacting 1976 legislationthat requires companies to notify the government of proposed mergers. Its hearings during government reviews of big airline, oil, or communications mergers typically focused on parochial concerns about the loss of jobs or airline routes in lawmakers’ home states.

Hearings highlighting Microsoft’s business practices were convened in 1998, by then-Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) just as a Democratic-run Justice Department under President Bill Clinton and a coalition of states launched the monopolization case against the software giant.

Hatch also helped the Justice Department fend off Microsoft’s lobbying effort to cut the Antitrust Division’s budget while litigating the case, which resulted in a judgment it had illegally defended its operating software monopoly. “That sort of political support is important,’’ First said.

Microsoft Case

The verdict that Microsoft illegally defended its Windows monopoly for personal computer operating software paved the way for Google, Facebook, Amazon and other Internet-based businesses to thrive, Columbia University law professor Tim Wu wrote in his book critiquing antitrust enforcement entitled “The Curse of Bigness.’’

Cicilline said his investigation entails examining case law enforced by federal courts that’s enabled big tech companies to gain power through a series of acquisitions of smaller companies.

Since the late 1970s, the courts have emphasized proof that a merged company could raise prices as the single most important basis for stopping an acquisition. Critics argue that courts should look beyond pricing power to assess behavior of digital firms like Google and Facebook, which don’t charge consumers.

Cicilline hired one of those critics, Lina Khan, to be a subcommittee counsel.

“One of the things we will look at closely are existing antitrust statutes and the existing law with respect to consumer welfare to determine whether there are additional factors’’ that should be considered, Cicilline said in an interview. The subcommittee will look at whether proposed mergers are “being viewed too narrowly or whether the statute itself needs to be updated or modernized.”

Judges are skeptical of cases that challenge the acquisition of a smaller rival that has the potential to become a competitor in the future. So the government’s inability or failure to prevent the loss of potential competition “is a very serious issue’’ for the subcommittee, Cicilline said. He’s cited Facebook’s purchases of Instagram Inc.’s photo sharing site and WhatsApp as acquisitions that enabled the social-media platform to gain economic power over time. The FTC cleared both deals.

Cicilline said he wants to examine why the FTC, when it was under the control of Democrats, brought no case against Google after it spent 19 months investigating whether the company unfairly favored its own products and services over other advertiser’s offerings.

“There hasn’t been a serious antitrust case there in decades,” he said.

Breaking Up

Top Judiciary Committee Republicans declined requests to comment about Cicilline’s agenda for potentially rewriting antitrust laws.

The subcommittee’s ranking member, Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.), issued a June statement that urged “caution against using antitrust for the purposes of `breaking up big tech’” because “we must be conscious of the many benefits that leading tech companies have brought to consumers.”

After the House announced its big-tech investigation, Mike Lee (R-Utah), chairman of the Senate Judiciary Antitrust Competition Policy and Consumer Rights Subcommittee, said in a statement that Congress should leave such inquiries to the FTC or the Justice Department because “antitrust is a highly technical inquiry, not something that lends itself to easy generalizations or blanket condemnations.”

In ruling on antitrust cases, courts interpret the broadly worded Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. Congress has seldom changed antitrust statutes since that act, underscoring the potential significance of the current initiative.

In 1914 Congress passed the Clayton Antitrust Act to give antitrust enforcers more power to challenge mergers and gave private plaintiffs the ability to seek treble damages for anticompetitive harm. That year, Congress also created the Federal Trade Commission Act to share competition enforcement with the Justice Department.

Congress in 1950 passed the Celler-Kefauver Anti-Merger Act to extend the Clayton Act’s enforcement provisions to include the anti-competitive acquisition of assets, not just corporate stock, and so-called vertical mergers of manufacturers with suppliers or distributors.

With assistance from Jorge Uquillas

To contact the reporter on this story: James Rowley in Washington at jrowley@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bennett Roth at broth@bgov.com; Katherine Rizzo at krizzo@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com