Disputed Gas Pipeline Seen Surviving Without Congress or Manchin

- Project continues to wind its way through agencies, courts

- Pipeline provisions likely to return in later legislation

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Efforts to speed a long-delayed, overbudget natural gas project in Sen. Joe Manchin’s home state by revamping federal permitting rules will play out in agencies and courts for now, after Congress balked last month.

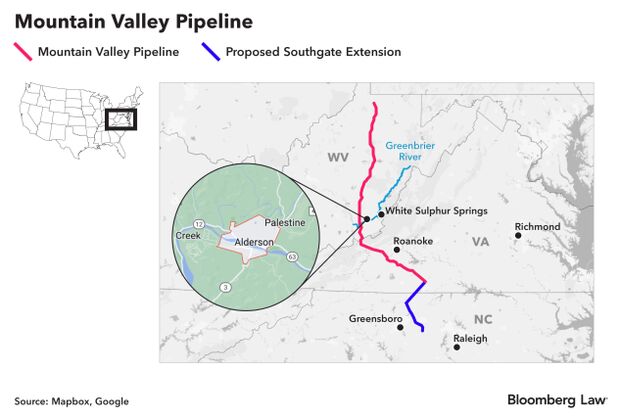

Manchin (D-W.Va.) failed to persuade his colleagues to back his energy permitting bill in stopgap spending legislation. But the Mountain Valley Pipeline in Appalachia could get the green light in coming months and go into operation by the second half of 2023 — the schedule the lead partner, Equitrans Midstream, proposed for the pipeline set to cross parts of West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina.

“It looks feasible to us,” said Christi Tezak, managing director of research at ClearView Energy Partners LLC, an independent energy policy research firm. “Anybody who is saying the Mountain Valley Pipeline is in limbo isn’t paying attention.”

The next key date in the pipeline’s journey is Oct. 25, when the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit will hear oral arguments in a case related to a Clean Water Act permit for Mountain Valley.

The Army Corps of Engineers, US Forest Service, and US Fish and Wildlife Service are reworking permits for the project following legal rulings against the agencies. US energy regulators approved in August a four-year extension of the project’s certificate until October 2026, giving the partially constructed pipeline plenty of time to be put into service.

BGOV Closer Look: Energy Permitting Revamp Still in the Pipeline

Last month, environmental groups Natural Resources Defense Council and Appalachian Voices filed a request for rehearing with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, arguing the pipeline developers failed to show “good cause” for the extension and that the commission’s environmental reviews are “stale.” FERC has 30 days to respond to the request.

Still, things are moving along, said Tezak, despite the lack of a mandated schedule for these types of projects—something Manchin’s permitting bill attempted to rectify. “Even just the simple act of setting a schedule would bound the madness,” she said.

Legislative Outlook

Manchin’s bill likely will return in some form when Congress comes back after the November midterm elections. It could hitch a ride on a must-pass vehicle such as the fiscal 2023 National Defense Authorization Act or a year-end omnibus government spending bill.

Why Democrats Are Fighting Over How to Permit Energy Projects

The midterms will determine who controls the House and Senate in January, and dictate both parties’ appetite for permitting changes. If Republicans win back both chambers, don’t expect a deal on Mountain Valley, Tezak said.

Even so, Republicans and many Democrats have expressed willingness to alter the federal permitting process.

“There’s a bipartisan group that wants to do it, including me,” said Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.), who objected to the Mountain Valley Pipeline provisions in Manchin’s legislation. Kaine and Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.) sponsored legislation (S. 4864) aimed at making FERC permitting more transparent and equitable, particularly when it comes to public input.

“I certainly have put that on the table and as the discussions get underway, I hope they’ll give it good consideration,” Kaine said of his legislation and the overall permitting overhaul effort. “That would build public confidence in a permitting reform bill.”

Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.) said he supports mandating timelines for energy projects as part of changes to permitting. “I’d like to have some sort of shot clock with teeth so that agencies can’t just sit on an application and do a pocket veto of things that otherwise meet every criterion,” Cassidy said. He added he’s not “a purist on procedure” — on the question of which legislative vehicle carries such changes.

Negotiations need to include more people than “just Joe and Chuck,” Cassidy said, referring to Manchin and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.).

Schumer made a deal with Manchin over the summer to consider the permitting bill in the government funding measure — in exchange for the West Virginia Democrat’s vote on the tax, health, and climate investment law. Manchin ended up pulling the permitting provisions out of the continuing resolution days before the end of the fiscal year, when it became clear they would tank the government funding measure.

Read More: Gas Pipeline Dealt a Blow as Manchin Withdraws Energy Bill

Manchin was upbeat just a day after withdrawing his bill, and expressed optimism about reviving the permitting overhaul after the congressional break.

“You’re always in negotiation, like any bipartisan negotiation,” Manchin told reporters last week. “We’ve done this before. This isn’t my first time. So, we’ve just got to find that sweet spot.”

‘Last Greenfield Pipeline’

Manchin has other cards to play to push the Mountain Valley Pipeline over the finish line.

As chairman of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, he exerts influence over the confirmation of FERC Chair Richard Glick, whom the White House nominated in May to another five-year term leading the commission. In March, the commission rolled back a controversial gas policy that would have scrutinized proposed pipeline projects, after Manchin called a hearing to criticize it.

Glick is still waiting for a confirmation hearing before Manchin’s committee; his term expires at the end of 2022. Asked recently when he might hold a hearing and whether he supports Glick, Manchin said he’s “still working on it.”

Tezak said that if Mountain Valley is finished, it will be “the last greenfield pipeline for a very long time” because of the success environment groups and private landowners have had opposing the projects over the last several years. A greenfield pipeline is a new proposed project rather than an expansion of existing networks.

Read More: Manchin’s Pipeline Could Be the Last of Its Kind, if It Survives

Anti-pipeline activists have become more sophisticated, and feel empowered by the defeat of Manchin’s initial permitting legislation. Environmental justice groups that came together to oppose the measure are now poised to resist the next effort at overhauling permitting, said Jean Su, senior attorney and director of the energy justice program at the Center for Biological Diversity.

“This bill brought everybody in the climate movement together,” she said. “It centered and prioritized communities in the shadow of the Mountain Valley Pipeline and every single fossil fuel community.”

A group of MVP protesters rallied at the Capitol the week the Manchin bill was pulled.

“This ain’t over until we say it’s over,” said Maury Johnson, a Monroe County, W.Va., native and ardent pipeline opponent. Johnson has helped lead the anti-Mountain Valley Pipeline movement for almost a decade. “As you may know, the Appalachians are a pretty fierce bunch of people when they are trying to stick up for their homes.”

With assistance from Daniel Moore and Stephen Lee

To contact the reporter on this story: Kellie Lunney in Washington at klunney@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.