Deregulation Window Closing 17 Months Before Trump Term Ends (1)

- All major deregulatory actions already in the pipeline

- Late-finalized rules more vulnerable to being overturned

(Updates with Vought in fourth paragraph. An earlier version of this story corrected the description of DOL rule in fifth paragraph and NYU study findings in 10th paragraph.)

Trump administration agencies are effectively running out of time to propose major cuts in regulations beyond what’s already in the pipeline, at least through the president’s current term, top officials of the Office of Management and Budget said.

The closing window means President Donald Trump will fall far short of his early pledge to business leaders to roll back 75% of all regulations. It reflects how long it takes to write rules to replace existing ones, a process involving multiple notices, public comment periods, cost-benefit analyses, agency reviews and, often, court challenges.

Trump’s administration is also facing the reality that if Democrats defeat him for re-election in November 2020 and gain control of the Senate, they could overturn regulations written in his last year in office, using the same law that Trump and a Republican Congress used to kill numerous rules from Barack Obama‘s administration.

“Agencies are continually pushed to find ways to roll back the red tape,” acting OMB Director Russell Vought said in an Aug. 8 interview with Bloomberg Government. “In the first two years of this administration it was easy to clear low-hanging regulations that were burdensome and duplicative.

“But as we come close to the end of the third year, we’re taking nothing for granted, so you should expect to see our larger priority regulations like CAFE and WOTUS to surface that will have an enormous and lasting impact on our nation.”

Agencies are now racing to finish key initiatives they’ve started during Trump’s term, including the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s move to relax fuel-economy (CAFE) standards for cars and light trucks, a Homeland Security proposal to modify a 1997 court settlement and allow lengthier detentions of migrant children, and the Labor Department’s rule, proposed in April, that would define who falls within the employer-employee relationship.

Any new proposals moving forward this term are likely to be modest and the administration will focus on structural changes to the rulemaking process, such as the memo issued in April that requires agencies to submit more cost data about their rules, the OMB officials said.

“From now through the end of the year and the first few months of the following year we expect agencies to drive home the important initiatives that they’ve begun,” said Paul Ray, acting administrator of OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

Wholesale deregulation has been kept in check by the reality that it takes one to five years to finalize a significant rule. Agencies must put thousands of hours into drafting a notice of proposed rulemaking, developing a sound statement of basis and purpose, and responding to critical public comment, paying close attention to the steps in the Administrative Procedure Act, executive orders, and OMB guidance on agency rulemaking.

Significant federal regulations are reviewed by OIRA before they are issued, with an average review time of 71 days. OIRA is charged with ensuring the proposed or final rule doesn’t conflict with existing laws and checks its regulatory impact analysis, cost-benefit calculations, and legal justifications.

Early attempts by Trump administration officials to shortcut the process resulted in a court defeat, or the agency withdrawing the rule after being sued, 94% of the time, according to an analysis by New York University School of Law’s Institute for Policy Integrity.

Replace, Not Repeal

Priorities listed by OMB officials include the Treasury Department’s Opportunity Zones rules governing the tax incentives for investing in low-income communities, and changes in the Interior Department’s rules for adding and removing protections under the Endangered Species Act. A set of rules was finalized and released Aug. 12.

Also important are new regulations that for decades to come will set the framework for development of commercial space exploration and drones, the officials said. In March, the Transportation Department proposed a new rule around launch and reentry requirements, while in February, it proposed a rule to govern how small unmanned aircraft can be operated over areas where there are people.

Priorities in immigration policy are being made through changes to the Homeland Security Department’s Public Charge and Flores rules. A final rule was released Aug. 12 to limit the public benefits used by immigrants, while OIRA is still reviewing the rule proposed in September 2018 to permit detentions of migrant children beyond the current 20-day limit.

Also of importance are the Environmental Protection Agency’s Waters of the U.S. (WOTUS) rule, which defines the groundwater subject to federal and state regulations; and changes in the Agriculture Department’s food stamp program, including how benefits are calculated and a work requirement for able-bodied adults as passed by Congress.

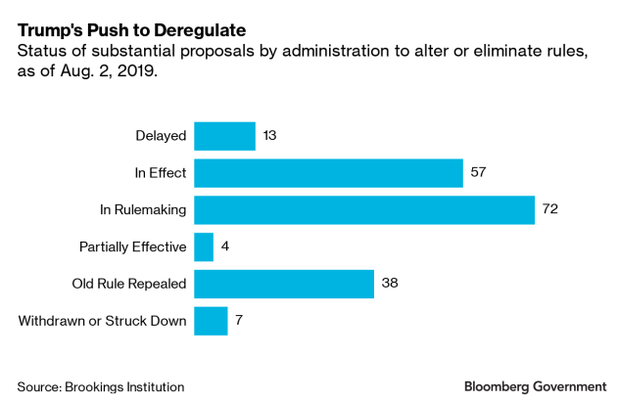

The Brookings Institution has been tracking agency deregulatory actions that it deems substantial since the start of the Trump administration, finding the majority of proposals are still in the rulemaking process.

“I think they’ll be able to finish very few of them, and then those they do finish they’re unlikely to be able to defend in court,” predicted Richard Pierce, law professor at George Washington University Law School and author of more than a dozen books on administrative law and government regulation.

Vulnerabilities

Rules finalized in the last year of an administration can be repealed under the 1996 Congressional Review Act (Public Law 104-121), frozen if they haven’t gone into effect yet, or stayed in court while their validity is being challenged, Pierce said.

The Trump administration used the CRA to great effect in 2017, overturning 15 Obama-era rules and thrusting the once-obscure statute into the spotlight.

Under the CRA, any rule finalized in the last 60 legislative days of a congressional session can be essentially vetoed within the first 60 days of a new Congress if a resolution is passed by both chambers and the president signs it into law. It becomes a factor following an election that changes party control of the White House and Congress.

“There’s kind of a catch-22, because on the one hand they want to hurry up with the CRA window in mind,” said Susan Dudley, director of the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center and OIRA’s leader during the final two years of President George W. Bush’s administration. “On the other hand, they’ve got to slow down to do their homework and get it right, or they’re going to get overturned in court.”

The exact date of the CRA window is difficult to determine in advance, but historically falls within May or June of a presidential election year.

“We could get a much better sense of when that would be once the 2020 calendar is released—it’s usually the House that is the determining factor,” said Daniel Perez, senior policy analyst at the GW Regulatory Studies Center. “Even then it’s not going to be precise, because of course they can fiddle with legislative days.”

At even higher risk of being overturned are midnight regulations, which are the unexpected rules rushed through in the waning months of a president’s administration, typically between Election Day and inauguration.

“If Trump loses, then we are in a midnight period and you could still see a flurry of activity to try and finalize rules, potentially trying to use interim final measures,” said Bridget Dooling, research professor at the GW Regulatory Studies Center.

To be sure, agencies will unveil this fall some new proposals in OMB’s unified agenda of regulatory and deregulatory actions, which is a semiannual list of all the rules agencies plan to advance over the next 12 months.

Real Repeals

Agencies have achieved significant deregulation since Trump took office through a combination of cuts, easing stringent rules and not issuing new ones, regulatory scholars say.

Not enforcing rules and delaying their implementation while attempting to rewrite them amounts to a period of deregulation, even if the courts ultimately ding them on the final rule, agreed Michael Livermore, law professor at the University of Virginia School of Law.

“Merely by not doing anything they’ve effectuated fairly successfully some level of deregulation,” Livermore said.

More important to CEOs than deep cuts in existing regulation is not having to confront a steady stream of new rules, said Marcus Peacock, chief operating officer at the Business Roundtable and a former member of the Trump transition team.

“The change in regulatory attitude—not necessarily the agenda—but the attitude of this administration has made a material difference to their businesses,” Peacock said. “And that comes mainly from the fact they’re not going to get unexpected regulations.”