Democrats Pitch Extreme Weather Plans As Biden’s Agenda Stalls

- Parties agree government needs national climate resilience plan

- Democratic bill would protect immigrant disaster workers

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

A high-level, national strategy to help communities better prepare and respond to extreme weather events is attracting bipartisan attention, as Democrats’ clean energy and climate agenda languishes in Congress.

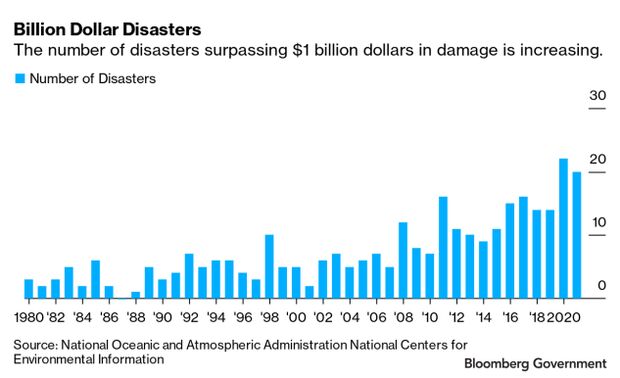

Wildfires, drought, and extreme temperatures are becoming more than a seasonal problem for many Americans. The number of billion-dollar disasters in the U.S. has steadily increased, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with 20 such disasters last year. Disasters in 2021 killed 688 people and cost a total of $145 billion in damages.

Federal recovery plans and laws are in need of an update to meet the current climate moment, according to Saket Soni, executive director of Resilience Force, a national nonprofit group that advocates for disaster recovery workers.“We see a vast resilience divide, a set of people living in homes and communities, no less prone to flooding but who don’t have the resources to recover,” Soni said in an interview.

Disaster planning, response, and recovery is mostly still dictated by the 1995 Stafford Act. In an effort to update that law, lawmakers on both sides have introduced legislation this month to elevate climate resilience to a White House post.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) this week unveiled a comprehensive bill to expand and improve pay and protections for the disaster recovery workforce, which is largely comprised of immigrants. The bill would also provide reliable federal funding for localities, particularly frontline communities, to devise climate resilience action plans and conduct regular risk assessments.

Many jobs that respond to disasters have labor concerns linked to them, according to Rachel Jacobson, the deputy director of the American Society of Adaptation Professionals. Jayapal’s bill is one of the first to address the needs of workers focused on climate adaptation, Jacobson said.

“Labor protections are one really important piece, and the other piece is quality of work performed,” she said.

Separate legislation from Democrats and Republicans in both chambers unveiled last week would require the federal government to craft a National Climate Adaption and Resilience Strategy every three years to help vulnerable communities prepare and respond to climate change.

Both bills direct the creation of a White House office, or a chief resilience officer, to coordinate the entire federal government’s strategy on weathering climate change. But that’s largely where the similarities end.

Jayapal’s legislation is more wide-ranging than the “National Climate Adaptation and Resilience Strategy Act” sponsored by Chris Coons (D-Del.) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) in the Senate, and Scott Peters (D-Calif.) and María Salazar (R-Fla.) in the House. The “Climate Resilience Workforce Act” addresses several thorny policy issues including climate, immigration, labor, and criminal justice reform. That means it might cost more than the $2 million annual investment over the next decade that the bipartisan measure proposes.

Jayapal, who has been working on her bill for more than year, said she doesn’t have a price tag yet, but that it can be “scaled up or scaled down” as it moves through the legislative process. The Washington Democrat, who also leads the Congressional Progressive Caucus, said the provisions in the bill ultimately are an investment in the future. “Whatever we spend on this is going to be cheaper than what we spend right now on climate disasters,” she said in an interview.

Labor Protections

The immigration-related provisions and measures ensuring formerly incarcerated individuals have access to apply for disaster recovery jobs are likely to face resistance, which Jayapal acknowledges.

Her bill would provide grants for workforce development and job creation, as well as establish stronger protections for workers, mostly immigrants, performing the dangerous, physically demanding recovery work after natural disasters. It would require the Homeland Security secretary to provide status and employment authorization for two years to immigrants seeking work or training in the climate resilience sector.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s permanent workforce has struggled to keep up with the never-ending crush of natural disasters and face staffing shortages, officials recently told a House congressional panel. The squeeze on FEMA makes the less protected and subcontracted transient workforce even more valuable—and vulnerable.

Jobs created by the grants in Jayapal’s bill would have to meet certain minimum labor standards, including classifying workers as employees, not independent contractors, except under limited circumstances. Workers would be paid a prevailing wage and guaranteed the right to collectively organize under the legislation.

The “largely low-wage, immigrant workers” in the industry should be employees to ensure that they’re not exploited, said Debbie Berkowitz, a former senior official with the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration who is now a fellow at Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor. “The workers that come in after to clean this up, whether it be an individual house or a building, or a public building, are facing all sorts of real hazards that can cause serious injuries or death.”

Moving Pieces

While the “National Climate Adaptation and Resilience Strategy Act” boasts high-profile bipartisan sponsors, one of the main aspects of the legislation—the creation of a chief resilience officer—doesn’t necessarily require an act of Congress. President Joe Biden could create and staff an Office of Climate Resilience through an executive order, similar to what the Bush administration did after Sept. 11, 2001, when it established the White House Office of Homeland Security.

Jayapal said she already has started making rounds to committee leaders about her bill, including Transportation and Infrastructure Chair Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) and Kathy Castor (D-Fla.), who leads the Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. Jayapal also is working to advance parts of her bill through the Civilian Climate Corps provisions in the current Build Back Better package (H.R. 5376).

“We are not committed to only moving the bill as a whole,” Jayapal said. “We are very open to and already talking about moving pieces of it in different pieces of legislation.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Kellie Lunney in Washington at klunney@bloombergindustry.com; Paige Smith in Washington at psmith@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Zachary Sherwood at zsherwood@bgov.com; Giuseppe Macri at gmacri@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.