`Crumbling’ Schools Spur Democrats to Renew Infrastructure Push

Students at Coughlin High School in Wilkes-Barre enter their school building through a shed, a safety precaution in case part of the school’s crumbling façade falls at the wrong moment.

Two elementary schools closed in Arizona after the district found structural defects that could pose safety risks to students. And in Baltimore, students wore coats to class after heaters broke. Some schools didn’t bother to open.

“It’s hard to educate people in schools that are crumbling,” said Rep. Bobby Scott (D-Va.), who introduced a $100 billion school infrastructure bill in 2017 that was co-sponsored by 119 House Democrats but stalled in the GOP-run House. “In a lot of areas that’s unfortunately what’s happening.”

With the new Democratic majority this year, Scott holds the gavel of the House Education and Labor Committee and plans hearings to show the need for better buildings and how many jobs can be created. Infrastructure is also a major priority for Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.). They’ll need to persuade Republicans who traditionally view school buildings as a state and local responsibility.

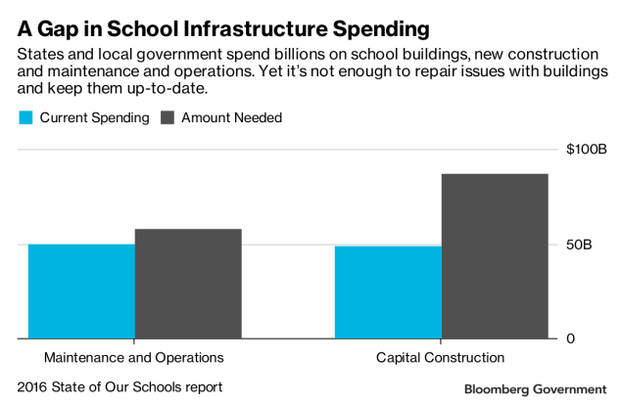

The federal government currently spends money to repair schools only in cases of disasters. That leaves states and localities pouring billions of dollars into fixing buildings each year, about $46 billion short of the needs, according to a 2016 “State of Our Schools” study by three groups: 21st Century School Fund, the National Council on School Facilities, and the U.S. Green Building Council.

While a federal study from the National Center for Educational Statistics found that three-fourths of schools were in good or excellent condition or better, at least half of all school districts said their facilitiesneeded major repair.

Dan Urevick-Ackelsberg, a staff attorney with the Public Interest Law Center which is suing Pennsylvania over inadequate funding for schools, said the state alone can’t get schools to where they need to be.

“Our federal government has the power to really knock this out,” he said. “There might not be a constitutional obligation, but there would sure seem like there’s a moral obligation to get it done.”

`Like an Old Car’

About 32 percent of school districts reported there were fewer funds available in 2017 than 2016 in a survey of 133 school districts by the magazine School Planning and Management. Only 12 percent said more funding was becoming available with the rest seeing no change or unsure of any change.

Some of that stems from a lack of state funding. While local governments provide about 80 percent of school funds, dozens of school districts and local groups have sued state lawmakers to boost school funding. Twelve states have pending suits and 46 states been sued since 1973, according to the Center for Educational Equality.

State officials overseeing school funding say it’s difficult to keep aging structures up to date and in line with increasing requirements for schools to be accessible for students with disabilities and up to health, energy, and safety standards, said Scott Brown, director of facilities for Maine schools.

“There have been different waves over the years of challenges that have not been kept up with,” he said. “It’s kind of like an old car,” he added. “You can renovate it to be an old car, but to renovate it to modern safety standard, it’s very difficult to do.”

Each year maintenance is deferred, issues grow more dire and more expensive said, Brad Montgomery, the director of school facilities in Arkansas.

“We need that additional amount to get over the hump and address some of the adequacy and sustainable,” he said.

Republicans Wary

Rep. Glenn Thompson (R-Pa.) has spent a lot of time thinking about school funding—before serving on the House committee dealing with education, he sat on the Bald Eagle Area School Board in rural Pennsylvania. But aside from helping bolster school safety, he doesn’t see a federal role.

“Where we have poor school conditions, it falls squarely on the backs of local and state officials, so they need to step it up,” he said. During his time on the school board he had to make difficult decisions on whether to consolidate schools, he said.

Rep. Virginia Foxx (R-N.C.), the ranking member of the House education committee, feels the Democrats’ 2017 infrastructure proposal for schools was irresponsible said spokeswoman Marty Boughton. She said the plan distracts from the limited and important role the federal government does have in supporting disadvantaged students.

Some Republicans are supportive of the federal government stepping in for schools. Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) signed on to a predominantly Democratic letter urging President Donald Trump to create a federal-state partnership to invest in school infrastructure. Trump himself has spoken of using federal dollars to fix schools, but his infrastructure plan unveiled in February 2017 lacked any specific funding for schools.

Lawmakers seemed more open to the idea in a December 2018 meeting with state facility directors than they had a year earlier, said said Mary Filardo, the executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, which helped coordinate the Capitol Hill visit with the the [Re]Build America’s School Infrastructure Coalition.

“It was very different,” Filardo said, “People were aware of the issues they were much more ready to talk about it. It was clearly much more on the front of their minds. “

Republicans also will be looking for ways to compromise with Democrats in a divided government, said Bob Van Heuvelen, who has lobbied on school infrastructure with VH Strategies.

“I’m not a Pollyanna but I would not be out of bounds to speculate that there will be some Republican support in the House and the Senate for doing something,” he said. “The politics are right, the infrastructure needs are overwhelming.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Emily Wilkins in Washington at ewilkins@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com