Covid Flight From Transit Forces Shift to Riders Without Choices

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Public transportation leaders are rethinking how to serve riders who depend on them, as they adjust to the possibility that many commuters who abandoned mass transit during the Covid-19 pandemic will never return.

Half the nation’s remote workers prefer to work from home permanently even if offices reopen, a May Gallup poll found. Employers nationwide are debating perpetual remote work options, led by the federal government and large technology companies such as Twitter Inc. and Shopify Inc.

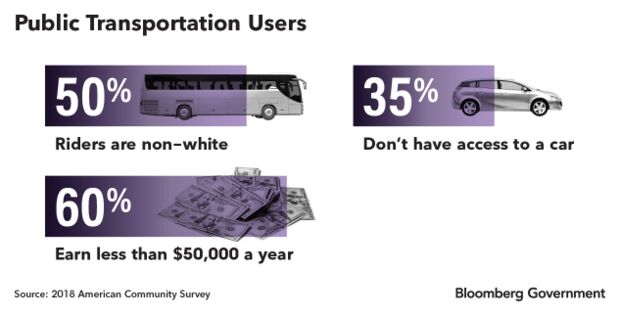

With commuters stepping away after sustaining downtown-to-suburbs rail networks for decades, those who can’t work at home and have few or no transportation alternatives more likely are low-income or people of color. Roughly half of transit riders nationwide before the pandemic weren’t White, and about 60% earned less than $50,000 a year, according to the Census Bureau. Some 35% don’t have access to a car.

“There may be fewer people heading into work every day,” said Danny Pearlstein, a transit advocate in New York City. For those who are, “their commutes are the commutes the rest of us are depending on.”

Transit agency leaders are asking Congress for as much as $36 billion in emergency aid to help weather the pandemic, in addition to the combined $25 billion the sector already received (Public Law 116-136). But that’s the short term. Regardless of whether they receive another bailout, public transportation systems nationwide likely can’t survive as set up now without continuing, massive rescues from the federal government or seismic shifts in how they operate.

Transit agencies are changing routes, eliminating services, or redesigning schedules. Looking longer term, government officials, companies, advocates, and urban planners are testing ideas such as subsidizing taxis, using smaller autonomous vehicles, and giving low-income commuters fare-free rides. Some officials are asking local voters for money.

“Public transportation is trying to be a little more fluid,” said Chris Pangilinan, head of public transportation policy for Uber Technologies Inc. “Now it’s still buses and trains for a mass majority of it. But also, the definition is ‘how do we connect people to economic and social opportunities in their cities in the best way?’”

Essential Services, Workers

As of late July, Monday passenger traffic on the Long Island Rail Road remained down about 78% from year-earlier levels, even with New York City starting to relax stay-at-home orders. Bus traffic within the city was off 45%.

Other cities show similar patterns, with narrower spreads.

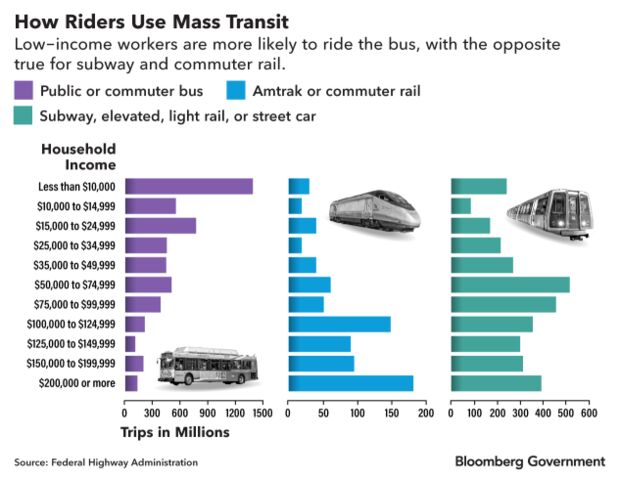

Workers in fields such as health care, retail, and food service don’t have the option of teleworking, even during a pandemic, and tend to rely more heavily on the bus than rail. The lower the household income, the more likely the worker depends on the bus — with the opposite true for subway and commuter rail — a Federal Highway Administration study in 2017 found. More than 80% of transit riders in the lowest fifth of household income rely on the bus, an analysis found.

In Chicago, home to one of the nation’s busiest rail systems, officials are redirecting buses to areas with a high concentration of transit-dependent riders, such as low-income neighborhoods in the city’s south and west sides, said Chicago Transit Authority president Dorval Carter, Jr.

In Cleveland, officials are considering beefing up bus frequency in the middle of the day because office-worker telecommuting has reduced demand at rush hour.

“That is a profound change for public transportation in America,” said Joel Freilich, a top official at the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority.

Rail Options Limited

Commuter rails built to carry white-collar workers from suburbs to downtown offices are relatively inflexible, leaving officials with few quick options to finesse dramatically lower ridership. They sent a letter to Congress in August to underscore their plight.

In Philadelphia, where passenger traffic on regional rail was down about 98% at the pandemic’s peak from year-ago levels, the transit system is offering a new three-day pass to attract office employees who may report to work on a shortened schedule, said Leslie Richards, head of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority. Even with commuter rail virtually abandoned, bus and subway ridership within the city was down only about 30% in July, she said.

Ridership on Caltrain, which runs through major technology hubs in California’s Bay Area, slumped by 95% in August compared with pre-pandemic levels, said Dan Lieberman, the system’s spokesman. Their riders likely can work from home or drive if they must go to an office: the average household income of a weekday rush hour commuter before the pandemic was $165,771, according to a 2019 report. More than a quarter earned $250,000 or more per year.

The system was in the middle of switching from diesel to electric power when the pandemic hit in March, Lieberman said. Officials haven’t halted the fully-funded project on the assumption, supported by their own research, that ridership will eventually return. A November ballot measure that would add a sales tax to fund Caltrain could also shore up finances in the meantime.

“We need to make sure we get through this period,” Lieberman said. “But at the same time, there’s a larger look at the growth of the system.”

Revenue Woes

Even before the pandemic, U.S. transit agencies typically couldn’t survive on fares alone. They relied on a combination of local, state, and federal subsidies to operate and make upgrades. Federal dollars made up less than 8% of public transportation agencies’ operating budgets and abut 35% of capital funds in 2018, the Federal Transit Administration reported.

Officials in a few cities are turning to voters to raise money to prevent transit cutbacks.

Cincinnati voters in May narrowly approved a sales tax increase that would provide as much as $130 million per year for bus networks and roads. In Seattle, voters will decide in November whether to approve a sales tax increase that would raise up to $42 million per year for bus service.

To raise money for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York lawmakers decided in 2019 to roll out a fee for automobile drivers entering Manhattan’s business core, the first of its kind in the U.S. Places such as San Francisco and Los Angeles are considering similar ideas.

The Seattle proposal would also provide transit passes for students and low-income riders, an idea activists have pushed nationwide. Bay Area Rapid Transit in California recently launched a discount for those with a household income of twice the federal poverty level or less.

This pandemic “further illuminates the need for really being a system that centers individuals who are really the poor transit riders,” said Monique López, a social justice planner in California.

Transit as ‘Second Class’

Fiscal conservatives have long argued that increasing federal spending on public transportation is nonsensical even in good times, and they now contend that the pandemic makes that clearer.

Senate Republicans criticized a bill (H.R. 2) the House passed earlier this summer that would increase federal transit spending over five years, and have slow-walked writing a competing proposal.

The government “should encourage business-like operations of transit systems” and use new technology to complement fixed-route, traditional service, Senate Banking Chairman Mike Crapo (R-Idaho), whose committee oversees public transportation, said in March. He didn’t offer details. Crapo, through a spokeswoman, declined a interview request.

“They’re like ostriches with their head in the sand,” said Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) about Republican support for public transportation emergency assistance.

Randal O’Toole, a researcher at the Cato Institute, which advocates limited government, called rail transportation geared to downtown workers “obsolete.” The federal government should focus on funding highways to create fairness for low-income Americans because transit is a “second-class” option, he said.

“A highway doesn’t care if you’ve got a Yugo or a Rolls-Royce, you get the exact same access to the road,” O’Toole said. He supports a mileage-based user fee to reduce congestion.

Currently, metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles and Washington’s Virginia suburbs have set aside lanes for drivers who pay tolls.

Network of Future

Public officials, urban planners, and private companies are accelerating work on ways to cut operating costs while serving riders.

Uber Technologies Inc. is partnering with public transportation authorities to provide subsidize taxi-like services. In April, Miami gave riders vouchers for Uber ride shares to cut down on running near-empty buses late at night.

In Los Angeles, urban planners are working on adding bikes and electric scooters to help people avoid a long walk to public transportation. “The game that we are playing is we want to bring choice to all communities,” said Dylan Jones, an architect at Gensler.

In Jacksonville, Fla., officials want to lure riders with shuttle reservations. Before the pandemic, the agency swapped 40-foot buses for on-call shuttles in 11 communities. Riders in those areas can now call and get a ride on their schedule instead of taking the bus.

Jacksonville is also focused on developing autonomous shuttles instead of boosting its elevated monorail, said Nat Ford, the local transportation agency’s top official. The agency used the shuttles to transport coronavirus tests from testing site to processing center.

Driver wages make up a large chunk of urban transportation budgets, said Alejandro Tirachini, a transportation researcher based in Chile. Both New York City and Chicago, home to two of the busiest U.S. transit systems, spent about 77% of their public transportation operating expenses on labor in 2018, federal records show. Automation would encourage public transportation agencies to add smaller vehicles, because large buses would no longer be as cost effective, he said.

“The pandemic has given us the opportunity to pause and reflect on what we currently provide in terms of our services, and we are using it frankly as the momentum to be the transportation network of the future,” Ford said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Courtney Rozen in Washington at crozen@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com; Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.