California Will Be First State With Its Own Privacy Regulator

- New agency to assume bulk of enforcement role

- Law will apply to data collected beginning in 2022

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The California Privacy Protection Agency will be the first of its kind tasked solely with enforcing privacy laws.

While the Federal Trade Commission can go after companies employing deceptive practices—such as including misleading statements in their privacy policy—it doesn’t have a singular focus on privacy like the California agency that will be created under the measure (Proposition 24) approved by voters Tuesday.

“It’s going to be on the lookout for violations,” said Cathie Meyer, a cybersecurity and privacy attorney at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP in Los Angeles. “We will see an uptick in investigations and potentially enforcement actions once this new agency is set up.”

The agency will enforce the California Consumer Privacy Act, which the state Legislature passed in 2018, giving Californians the right to know what personal information is being collected about them and ask that it be deleted.

A new category for sensitive personal information is part of the ballot measure and includes biometric identifiers, sexual orientation, and precise geolocation, among other data. The measure also expands the types of data breaches for which consumers can sue companies to include email addresses and password combinations.

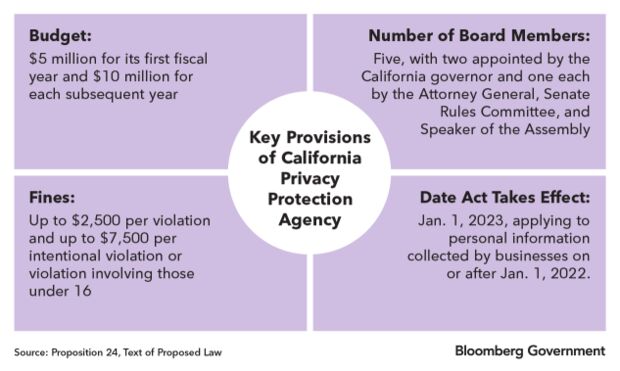

Businesses that handle large amounts of data will potentially face penalties if they don’t comply. The new agency can levy administrative fines of up to $2,500 per violation or $7,500 per intentional violation or violation involving those under 16 years old.

“Establishing a unique agency to enforce privacy rights is a direction we’ll see some other states go in,” said Reece Hirsch, co-head of Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP’s privacy and cybersecurity practice. “We haven’t seen that kind of approach in the U.S.”

Whether and how quickly other states follow California’s lead may depend on how smoothly the agency becomes established before it begins regulating companies on Jan. 1, 2023, attorneys say.

The new agency will be overseen by a five-member board with expertise in privacy, technology, and consumer rights. Members will be appointed by the governor and other elected state officials. It’s set to receive $5 million its first fiscal year and $10 million in each subsequent fiscal year from the state’s general fund.

That funding may quickly be consumed by personnel, administrative, and other startup costs, said Jen King, director of consumer privacy at Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society.

“I fear it’s not enough to get off the ground,” King said. “This new agency could be a new leader for the nation” if sufficiently funded and implemented, she said.

Ireland’s Data Protection Commission, by contrast, had a 2020 budget of 16.9 million Euros, or about $20 million, and a staff of 150, according to a commission spokeswoman.

Alastair Mactaggart, the Bay Area real estate developer who largely financed the ballot initiative, said having money set aside for the agency will help avoid “appropriation fight sessions” in the state Legislature that could hobble it financially.

The agency, unlike European data protection authorities, can decide whether it wants to investigate a particular case, said Caitlin Fennessy, research director of the International Association of Privacy Professionals. It will be required to hold off on an administrative action or investigation if the state attorney general wants to proceed with an investigation or civil action, according to the measure.

Path Forward

The attorney general’s office will loan the new agency lawyers while it’s being established. State legislators likely will have to amend ballot initiative language to remove loopholes in the law, said Jackson Lewis P.C. associate Jerel Pacis Agatep.

But even with potential hiccups, the new agency will require companies to remain vigilant about their data practices.

“California is already pretty far out ahead,” said Justin Yedor, an associate at McGuireWoods LLP in Los Angeles. “Most states don’t even have the laws that would apply, let alone a regulator solely devoted to enforcing those laws.”

The agency could serve as a blueprint for other states. Seventeen states have considered similar privacy measures, and it’s possible they would try to align more closely with California’s law, said Dominique Shelton Leipzig, co-chair of Perkins Coie LLP’s ad tech privacy and data management practice.

“Almost every state in the country has been in communication with our California folks to look at the model,” she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jake Holland in Washington at jholland@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Keith Perine at kperine@bloomberglaw.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.