Biden Plan to Fix Organ Transplant Network Promised More Support

- Lawmakers, patient groups push to end long-time monopoly

- Backlog blamed for deaths as ailing patients await transplants

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Longtime critics of the group that manages the nation’s organ donation system are launching efforts to ensure the success of a Biden administration plan to break up the monopoly at the top of the industry.

The current system is plagued by technology failures, logistics problems, and a contracting system that’s allowed one group, the United Network for Organ Sharing, to manage US transplants for 37 years without enough oversight, lawmakers and advocates for changes say.

HRSA, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services, is proposing breaking up certain parts of the contract UNOS holds to introduce new players to the system, a move backers say is long overdue. Past efforts stalled, so this time they are preparing legislation and forming groups to push the changes through.

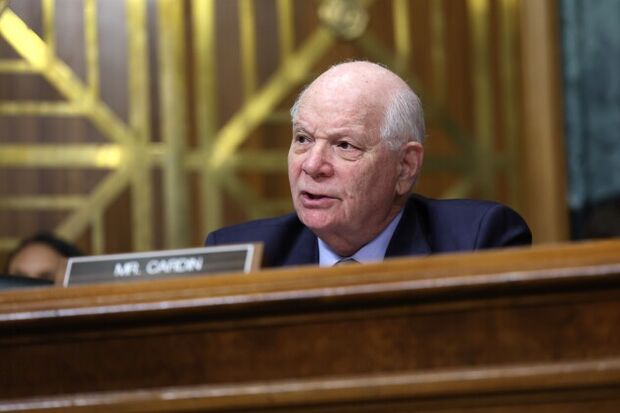

“We’re going to watch everything very closely,” Sen. Ben Cardin (D-Md.) said. “There’s a lot of progress that can be made be reforming this monopolistic organization.”

More than 104,200 people are on the national waiting list to get kidneys, livers and other organs from deceased donors—a backlog that contributes to 17 dying each day, according to data from the Health Resources and Services Administration.

HRSA is asking Congress to “expand the pool” of eligible organizations to run this network. The Biden administration is also seeking to nearly double the budget for organ procurement and transplantation next year, to $67 million from $36 million in fiscal 2023.

‘Critical’ Oversight

UNOS’ job has been to manage the national transplant waiting list and run the database that matches donated organs with people seeking them. It sits atop a network of hospitals, transplant centers, and organ procurement organizations that together save thousands of lives each year.

That work is lucrative: UNOS reported $71.3 million in revenue in 2020 and almost $120.9 million in assets, its latest available tax fillings show. Much of that revenue came from registration fees paid by transplant centers, and the group holds a $6.5 million-per-year government contract for the work.

That contract is up for renewal this year.

In addition to seeking more money for the system, the Biden administration wants to give more independence to the board that oversees the network managed by UNOS, as well as improve the technology that connects donors and recipients. Some details around that proposal haven’t been released.

Read More: Racial Discrimination in Organ Transplants Alleged in Lawsuit

But continued oversight is “critical,” Jennifer Erickson, a senior fellow at the Federation of American Scientists who worked on organ donation issues for the Obama administration, said. “UNOS cannot be allowed to use taxpayer funds to protect its individual business operations at the expense of an open and fair competition run in patients’ interests,” she said.

Anne Paschke, a spokeswoman for UNOS, said the group supports the proposed changes, including a competitive and open bidding process.

“A process open to organizations with diverse offerings and expertise, that meet the requirements of the contract and are focused on ensuring continuity of service to patients, may be beneficial,” Paschke said in an email.

Lobbying Clout

UNOS and groups in its network have a history of ratcheting up their lobbying amid attempts to change the transplant system.

UNOS spent about $120,000 per year on lobbying from 2015 to 2019, then almost doubled the number of lobbyists working for the group in 2020, federal filings show. That year—when regulators were proposing to overhaul rules for organ procurement groups and lawmakers launched a major investigation of UNOS—the group spent $280,000 to hire seven lobbyists. Last year the group spent $190,000 on lobbying.

UNOS is “actively participating in these discussions and have offered our expertise in the spirit of collaboration,” Paschke said when asked about the ramped-up lobbying.

Patient groups such as the National Kidney Foundation say UNOS is likely to remain a major part of the US organ transplant system even if the system is revamped. The problems plaguing the system extend beyond the nonprofit’s sole control of a major government contract, they say.

However, lawmakers and others who’ve sought changes for years say it’s time to end UNOS’ monopoly.

Watching Closely

The transplant network has “failed at all levels, ” Grassley said at a March 22 Senate Finance Committee hearing. The Iowa Republican, who started probing issues around organ donation and transplantation almost 20 years ago, praised the HRSA proposal.

“I’ve been looking into this network a long, long period of time. The problems have gotten worse,” Grassley said.

Grassley also said the committee had heard “credible allegations” against UNOS of threatening whistleblowers, without elaborating.

Paschke said UNOS takes “any and all allegations” of retaliation seriously and would work with Grassley to look into the issue.

Senators and congressional staffers who’ve investigated the transplant system told Bloomberg Government they’re watching progress on the HRSA proposal and are mulling legislation to bolster the agency’s power, if needed.

Cardin said he’s starting a working group with other members of the Senate Finance Committee—where he heads a health panel—to keep tabs on HRSA’s proposed changes in coming months.

A Finance Committee investigation published last August, led by Sens. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), Grassley, Cardin and others, showed 70 donor recipients died related to disease from donated organs between 2008 and 2015, and that thousands of donated kidneys are discarded each year partly due to logistics and transportation errors.

Lawmakers laid much of the blame for those problems on UNOS: Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) told Brian Shepard, the group’s chief executive officer, in an August hearing that “you should lose this contract.”

That investigation and pressure on UNOS from senators was crucial, Erickson said, to build political will for the changes proposed by HRSA.

A Finance Committee staffer familiar with discussions who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss pending legislation said lawmakers are considering legislation to assist HRSA in seeing its proposal through, although details aren’t final. Another panel, the Senate HELP Committee, has jurisdiction over HRSA.

There’s concern UNOS will try to undermine any changes after the organization didn’t fully comply with requests for information from the committee, the staffer said. The Finance Committee issued a subpoena to UNOS in 2021 as part of its investigation—the first time in about a decade the committee had to subpoena for records.

Paschke denied that the group acts to undermine critics and said it would work with lawmakers.

Pushback on Overhaul

Others who’ve tried to improve the organ transplant system in the US say they’ve seen similar pushback against changes.

Bryan Sivak, chief technology officer at the Department of Health and Human Services from 2012 to 2015, recalled once organizing a meeting with organ procurement organization and transplant executives to discuss ways to improve the technology that helps match donated organs with those who need them. Instead, he said, he heard only organized opposition to any changes.

“The whole purpose of the call was to scare me away from actually engaging in fixing any of the issues I wanted to talk about,” Sivak said.

Greg Segal, CEO of Organize, a patient advocacy group that started with a goal of creating a national organ donation registry, said his group went on to push for better oversight of UNOS and performance metrics for organ procurement organizations, which act as middlemen between donors and transplant centers.

“HHS needs to keep a close watch on UNOS’ efforts to undermine competition through retaliation and harassment of any stakeholders who support reform, including even patients and caregivers,” Segal said.

Two days after HRSA announced its proposal to overhaul its contract and make other changes to the organ transplant network, UNOS’ past president, John P. Roberts, along with two professors of surgery, wrote an op-ed pushing back on critics. The trio noted the record-breaking number of successful organ transplants and called for increasing the organization’s budget.

Roberts said in an interview the op-ed was meant as a response to what he called unfair criticism of UNOS from lawmakers and others.

“There’s a lot of criticism from people who don’t have a good sense for how this system works or how complicated it is,” he said.

Researchers have found the number of organs being donated in the US rose in recent years partly due to skyrocketing drug overdose deaths, which make more organs available.

Abe Sutton, who worked at HHS during the Trump administration, said there was also debate back then about taking responsibility away from HRSA and creating an agency solely focused on overseeing the system.

“There’s a history of lack of action and definitely there is going to be pressure not to see change and not to follow through,” Sutton said.

Patient advocates say the challenges facing the organ transplant and donation system in the US extend beyond UNOS and that the federal laws around organ donation have long blocked competition.

Sylvia Rosas, president of the National Kidney Foundation, said by law only nonprofits with expertise in organ donation could hold the contract to run the national organ procurement and transplantation network.

“It basically describes the awardee in such a way that UNOS is the only viable candidate,” she said.

Part of the problem is organ procurement organizations aren’t collecting as many organs and they could be, Rosas said. The demand for organs could be larger than the reported waiting list because no one collects data on people who should get a replaced kidney or liver but for some reason don’t apply, she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Ruoff in Washington at aruoff@bgov.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

and John P. Martin at jmartin1@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.