Biden ‘Middle Ground’ on School Testing Fails to Please Everyone

- Mandates statewide tests, but allows accountability waivers

- Testing divides Democrats, educators, student advocates

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The Biden administration sought to thread the needle on a vexing debate over school testing nationwide, but the decision this week left some on both sides of the issue unsatisfied.

The Feb. 22 guidance to state education leaders said it won’t suspend federal mandates for statewide testing for a second straight year, while offering waivers on high-stakes accountability measures. It left many details unresolved, thanks to wide discretion granted to states on whether to shorten tests, push them back, or modify exams to meet local circumstances.

Teachers unions—closely aligned with the administration—complained that blanket testing waivers weren’t granted. Civil rights advocates and other public interest groups raised fears that a patchwork of local assessments would cloud data on vulnerable children who may be falling behind.

“The administration is trying to accomplish two things at once that are just at odds with one another,” said Elena Silva, director of elementary education at the think tank New America. “We should both test students because we need the data, and also recognize we can’t test all students effectively. Both are true.”

The debate over school testing requirements has been a defining feature of federal education politics for the past two decades, ever since Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act. States got new flexibility on student assessments in a 2015 reauthorization of the federal K-12 education law (Public Law 114-95) that replaced No Child Left Behind.

The pandemic last year led the Trump administration to grant all 50 states blanket waivers on testing requirements as schools closed across the nation. With millions of students still learning from home almost a year later, many states and local education leaders asked for tests to be suspended for another year.

Influential congressional Democrats and advocates for disadvantaged students argue tests will show where students are falling behind during the pandemic.

Urgency to Act

The Biden administration announced the new testing policy before Education Secretary nominee Miguel Cardona wins Senate confirmation; the final vote is expected next week. The rapid action shows the urgency of getting more clarity to states with looming test windows.

“Statewide assessments are important to identify what extra support schools need to help their students get back on track and to ensure every student has an equitable opportunity to succeed,” said Bobby Scott(D-Va.), chair of the House Committee on Education and Labor, and Patty Murray (D-Wash.), chair of the Senate, Health, Education and Labor Committee, in a joint statement on the Biden administration’s new guidance.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers union, said suspending accountability measures was a good start, but the Biden plan “misses a huge opportunity” to allow for use of alternative assessments when educators are struggling through a tumultuous school year.

After former Education Secretary Betsy DeVossaid last fall that states shouldn’t expect new testing waivers, Weingarten said the stance didn’t reflect reality. Scott and Murray backed DeVos’s position and have pushed for new assessments this year.

Middle Ground

The federal government requires states to assess students each year, but allows significant discretion over how tests are crafted and used to hold schools accountable.

The new guidance this week said state testing windows could be pushed back as late as the beginning of the next semester. It encouraged states to extend the testing period for English learners in particular.

The intent of such flexibility “is to focus on assessments to provide information to parents, educators, and the public about student performance and to help target resources and support,” Ian Rosenblum, acting assistant education secretary, told state school chiefs in a letter Feb. 22.

SATs, Once Hailed as Ivy League Equalizers, Fall From Favor

As chief of Connecticut state schools, Cardona advocated for both reopening school classrooms and testing students this spring.

He doesn’t support applying the same requirement for student assessments to all states, or bringing pupils back to classrooms just for standardized tests, he told lawmakers at his confirmation hearing this month.

At the same time, without assessments, “it’s going to be difficult for us to provide some targeted support and resource allocation in the manner that can best support the closing of the gaps that have been exacerbated due to this pandemic,” he said.

Several studies based on fall assessments found students were starting the year further behind, compared with before the pandemic. McKinsey & Co. Inc. reported students of color in particular were harmed.

‘No Clear Pattern’

States including Texas, Missouri, and Tennessee have already planned to test students but forgo using results for school accountability or teacher evaluations. That decision had no apparent connection to geography or partisan control—officials in Georgia, South Carolina, and New York had all urged the Education Department to grant new testing waivers.

All states were at the very least considering changes to their accountability regimes this year, said Anne Hyslop, assistant director of policy development and government relations at the Alliance for Excellent Education, an education nonprofit.

Waiving those standards “will help alleviate some concerns about validity of the data, if you know the data aren’t going to be used for school accountability,” Hyslop said.

School Testing Is Waived for Most States as Campuses Shut Down

In Illinois, whose state superintendent had also urged the Education Department to grant a new testing waiver, a group of local school district leaders told Cardona that normal standardized tests would disrupt learning.

The Elgin Area School District in Chicago’s northwest suburbs is already collecting data on student progress through the Measures of Academic Progress exam developed by the nonprofit research firm NWEA, said Tony Sanders, the district superintendent.

“I’d be glad to share that data with any member of Congress,” he said ahead of the Education Department’s announcement this week. “But please don’t make me lose six to seven days of instructional time with my kids.”

Measuring Inequities

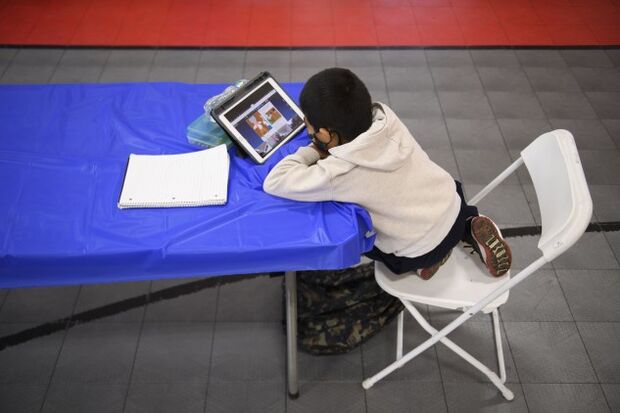

The federal guidance anticipates some concerns about disrupted learning by allowing states to assess students remotely. Many testing skeptics say disadvantaged students still struggle to get access to computers and wireless internet connections almost a year into the pandemic.

Education equity groups told Cardona this month that another year without tests would leave states in the dark about how far disadvantaged pupils have fallen behind.

Terra Wallin, associate director for P-12 policy at the Education Trust, which supported new tests, said advocates are pleased the Education Department won’t grant states blanket waivers from assessments. She said it was concerning, however, that the document offers additional flexibility to states based on local conditions.

“That’s what we’ll be watching closely,” she said. In Michigan, for example, the state allowed school systems this year to choosewhich test they used for students, raising the possibility there may not be comparable statewide data, Wallin said.

“You could have some states say they’re not going to give assessments, period,” she said.

Rethinking Pandemic-Era Testing

The Biden guidance is an encouraging sign the federal government is moving away from a rigid approach to testing, Stephen Sireci, director of the Center for Educational Assessment at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, said.

“We’re starting to see the dismantling of the No Child Left Behind, end-of-year summative assessment model,” he said. “It’s 20 years old. It’s time for a change.”

A fight is still coming over a broader shift away from standardized testing, Andy Rotherham, co-founder of Bellwether Education Partners and a White House official under President Bill Clinton, said.

“If the Biden administration were completely anti-test, they wouldn’t have carved out a pragmatic middle ground here,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Andrew Kreighbaum in Washington at akreighbaum@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com; Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.