Bad Bridges Stoke Safety Fears as Infrastructure Talks Flounder

- ‘Absolutely, unbelievably dangerous’ bridge spans cited

- Memphis bridge crack exposes broader oversight, funding issues

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Ed Evans, a Democrat in West Virginia’s House of Delegates, says drivers in the state’s rural southern counties regularly pass over bridges that “would scare you to death.”

He describes structures with rebar sticking out, and massive holes in the cement where bridges are held together with metal guard rails. “They are absolutely, unbelievably dangerous,” Evans said.

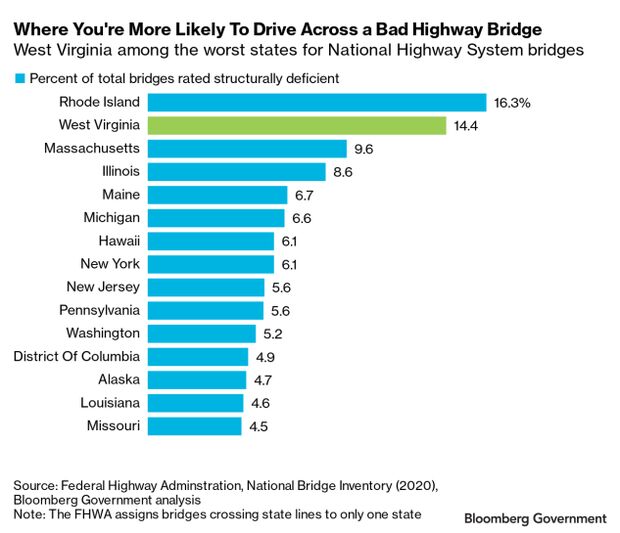

The federal government considers about 14% of West Virginia’s highway bridges to be in poor condition, making it the second-worst state by that measure, according to a Bloomberg Government analysis.

The plight of the nation’s decrepit bridges recently made headlines when a crack was found in a key beam supporting the Interstate 40 span over the Mississippi River in Memphis, Tenn. The bridge has been closed since May 11. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg visited in June to hear firsthand about the impact of the closure and to talk up President Joe Biden’s massive infrastructure plan.

“Our country’s got some work to do,” Buttigieg said, standing in front of the bridge. “We have 45,000 bridges in poor condition in this country and Americans cross those bridges 178 million times every single day.”

Attempts to reach a bipartisan deal for Biden’s package hit a hurdle this week, making it increasingly likely Democrats will have to go it alone on any infrastructure spending—and leaving questions about funds and priorities for any bridge repair effort.

Bipartisan Group Agrees on $1.2 Trillion Infrastructure Plan

Persistent Problem

The Department of Transportation estimated in 2019 that it would cost $125 billion to make all fixes that are economically justified. That cost must be weighed against the economic losses that can result from a bridge disruption.

“When a piece of road fails, you can put a patch on it, you can divert traffic, you can detour,” said David Lawry, a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. “But when a bridge fails, the road is done; you can’t go anywhere.”

The most recent Biden administration proposal appears to fall short of the funds needed to restore all bridges to top condition. The president’s initial $2.25 trillion infrastructure package proposed $40 billion for a bridge investment program. The plan specifically singled out fixing the 10 most economically significant bridges, to be determined by a competitive grant process. It also called for repairing the worst 10,000 smaller bridges.

Biden later dropped his offer to Republicans to $1.7 trillion, cutting the proposed funding for roads, bridges, and major projects. Those talks ended June 8. A separate bipartisan group of senators is working through its own proposal, while Democrats are also eyeing the budget reconciliation process that bypasses the need for Republican votes in the Senate.

Biden, GOP’s Capito End Infrastructure Talks Without a Deal

Worst Highway Bridges

With more limited funds, a crucial question will be which bridges get priority, with Biden’s fiscal 2022 budget only laying out vague criteria of spending on bridges “most critical to economic activity and least resilient to climate change.”

There are currently more than 4,500 poor bridges along the National Highway System, a network designated as important to the U.S. economy, defense, and mobility. Others in the network may also be in poor shape but not yet discovered—like the Memphis bridge.

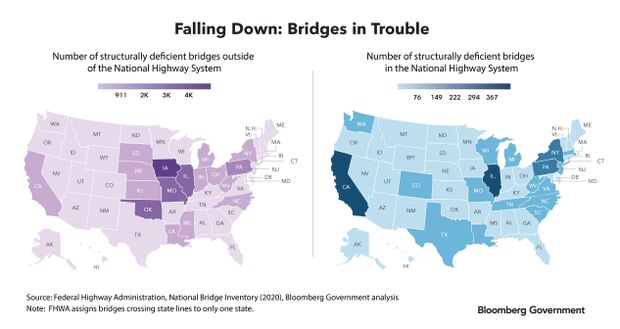

The highest numberof the network’s bad bridges dot the roads of California, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and New York, though 15 states have triple-digit tallies of poor-condition bridges—and nearly half of U.S. states have more than 50.

California is also home to four of the 10 bridges in poor condition that carry the most traffic.

Beyond the National Highway System, the Midwest in particular has thousands of deficient bridges. Iowa alone has more than 4,500.

‘Begging for Bridge Repair’

Residents of West Virginia are fortunate to have influential lawmakers involved in the infrastructure debate.

Republican Sen. Shelley Moore Capito played a major role in negotiating the infrastructure plan before the White House halted talks, while the administration’s hope of going forward with a package without the GOP relies heavily on her fellow senator from the state, moderate Democrat Joe Manchin.

“I just spent two weeks at home. We toured a lot of road and bridge projects that are ongoing that we need to give our governors the flexibility to pursue forward,” Capito said in April.

But not all West Virginians are confident they’ll get help, particularly in rural, economically struggling areas.

Among the worst are three small bridges that cross over Tug Fork Creek. Evans, the West Virginia Delegate, said losing any of those bridges would further isolate the already rural and remote town of Davy. One bridge, rated poor, is adjacent to a hospital. The other two were rated “fair” by the slimmest of margins.

“I’ve been on my hands and knees begging for bridge repair,” Evans said. “They’re fine at fixing the big bridges, but the little ones are harder.”

Bridges may also get funding through a five-year surface transportation bill that lawmakers must pass by Sept. 30. The House version of that bill (H.R. 3684) revived earmarks, a previously maligned practice in which lawmakers request money for specific local projects.

Democrats’ $547 Billion Highway Bill Advances in House Panel

Dangerously Congested

One of the most politically high-profile bad bridges, the Brent Spence Bridge between Ohio and Kentucky, has been a pet issue for Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (Ky.). McConnell has indicated he would fight the current Biden infrastructure plan, even if it meant funding for the project.

But the bridge, which spans the Ohio River south of Cincinnati, is a prime example of how “bad” or even “dangerous” can have different meanings. That’s because its condition isn’t rated among the nation’s worst—yet other factors converge to make it a serious problem.

When it was built in 1963, the Brent Spence Bridge was intended to serve one expressway: Interstate-75. Years later I-71 and I-74 were also routed over the bridge between Cincinnati and Covington, Ky., creating congestion and strain on the aging structure.

The span is also very narrow, leading to numerous accidents each year as motorists cross a structure never intended to support so much traffic.

Groups on either side of the river also have different visions for the scale of the bridge after repairs and expansions, including over lane expansion and tolls. One thing is clear: the status quo isn’t sustainable.

“The U.S. economy depends on it, and if it were to go down and break, you would have a major disruption that costs trillions of dollars in lost productivity,” said Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley.

What’s At Stake

Back in Memphis, Adel Abdelnaby, a civil engineering professor at the University of Memphis, said he recommended in January 2019 that sensors be installed to detect the types of cracks inspectors missed. State officials didn’t take up his recommendation.

“It’s very common that an inspector goes to the bridge, and then they cannot access some parts of the bridge because of safety concerns,” Abdelnaby said.

Bipartisan Roads Bill Set for Vote as Groups Lament ‘Status Quo’

“It’s kind of a shame that Memphis has to be the poster child for infrastructure failure,” Rep. Steve Cohen (D-Tenn.), who attended the bridge event with Buttigieg, said in Memphis. “But because of that, we give it a whistle, a canary in the coal mine, to the rest of the country about what they need to look out for in the way of infrastructure deficiencies and possible problems.”

Abdelnaby said many older bridges weren’t built based on a rigorous analysis, or with assurance that the design and lifespan can extend for many years.

“Our infrastructure is aging,” he said. “We just need to spend more money, put more funds into monitoring bridges to predict these cracks before they happen and become a problem.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Aaron Kessler in Washington at akessler@bloombergindustry.com; Jasmine Ye Han in Washington at yhan@bloomberglaw.com; Lillianna Byington in Washington at lbyington@bloombergindustry.com; Valerie Bauman in Washington at vbauman@bloomberglaw.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John Dunbar at jdunbar@bloomberglaw.com; Sarah Babbage at sbabbage@bgov.com; Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.