Asian Communities Push for Representation as Population Booms

- Clout divided among state and federal lawmakers

- ‘Black and White’ voting law doesn’t serve multiracial U.S.

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Southern California’s Little Saigon, where thousands of refugees settled after the Vietnam War, is the largest Vietnamese diaspora community in the United States.

But its roughly 200,000 residents across about 30 square miles are represented by three different members of Congress, a divide that advocates say has diluted the community’s voice.

It’s among the enclaves that could gain political clout as the populations of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders balloon nationwide. Advocacy groups are seeking to keep those “communities of interest” whole in the absence of federal voting rights protections. Those protections exist to shield historically marginalized voters, but rarely have applied to Asian communities because of their size and voting patterns.

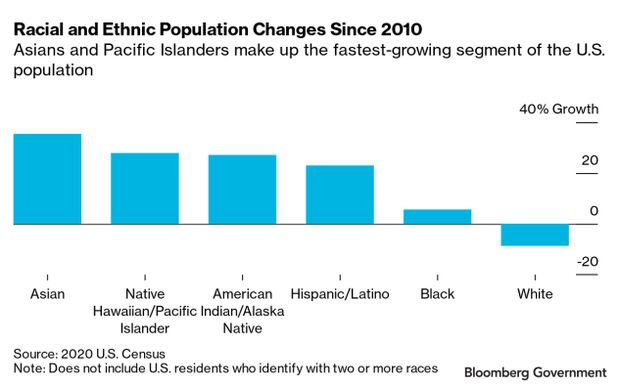

The number of people identifying as Asian grew by more than 35% nationwide from 2010 to 2020, and the number of Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders increased by almost 28%, according to the 2020 U.S. Census, making those the two fastest-growing racial groups in the country. That’s not including the millions of people who identify with one or more other race in addition to Asian or Pacific Islander.

Southern Gains

In North Carolina, a state that’s gaining a seat in Congress, the Asian population grew by more than 64%, with growth concentrated around the Charlotte and Raleigh metropolitan areas. In Texas, which will have two more U.S. representatives in 2023, that population also grew by 64%, with hundreds of thousands moving to the Houston and Dallas suburbs.

In Forsyth County, Ga., about 40 miles northeast from where four Asian women were fatally shot earlier this year, the Asian share of the population grew from 6.2% to 18%.

The number of Asian elected officials has been growing, too. For example, voters this past Tuesday elected three mayors of Asian descent: Michelle Wu in Boston, Aftab Pureval in Cincinnati, and Bruce Harrell in Seattle.

Housing, immigration, and deportation are the top federal issues affecting Little Saigon, said Vincent Tran with VietRISE, which advocates on behalf of Vietnamese and other immigrant communities in Orange County, Calif., where Little Saigon covers parts of the cities of Fountain Valley, Garden Grove, Santa Ana, and Westminster.

“Because there isn’t one person representing all of Little Saigon, I think some of those domestic-issue concerns have been either not as prioritized as we would like, or they’ve been kind of pushed to the side,” Tran said. He’s asked the California Citizens Redistricting Commission to unify the area as it redraws the state’s political maps ahead of a Dec. 27 court-ordered deadline.

Little Saigon isn’t the only Asian community that’s been divided. Sunset Park in Brooklyn, N.Y., which has a large Chinese and Indian population, is represented by three state senators. And in Texas’s new congressional districts map, approved Oct. 25 by Gov. Greg Abbott (R), two North Dallas counties where Asian American populations grew significantly are split among four congressional seats.

Small Bloc

Historically, Asian American neighborhoods haven’t voted in a large enough bloc to grant them protections under the Voting Rights Act. That 1965 law bars politicians or other line drawers from creating districts that deny minority voters an equal opportunity to participate in elections.

A 1986 U.S. Supreme Court decision set three conditions to determine a legally protected racial or ethnic community of interest. First, the minority group must demonstrate it’s large and geographically compact enough to constitute a majority in a district; second, the group must show it’s politically cohesive; third, there must be evidence that the White-preferred candidate typically beats the minority group’s candidate of choice in elections.

“One of the challenges nationwide for Asian American communities is making the case that they should be kept together as a community of interest” when the community doesn’t meet those criteria, said Sara Sadhwani, a Democratic commissioner with California’s redistricting commission, the bipartisan body determining the state’s congressional, state legislative, and Board of Equalization boundaries for the next decade.

Voting Patterns

The increase in the Asian, Latino, and multiracial population over the past decade is challenging the relevance of the 56-year-old voting rights law, said Michael Li, senior counsel for the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

“The Voting Rights Act was really designed for a Black and White world,” Li said. It “was not really designed for a diverse, multiracial world that isn’t necessarily starkly segregated.”

Unlike Black Americans who overwhelmingly vote for Democrats, Asian communities historically have diverged on political preference. Vietnamese Americans have typically voted for Republicans, Indian Americans support Democrats, and Chinese Americans are split, with a large number in California registered with no party preference, said Sadhwani, an assistant professor of politics at Pomona College whose research centers around Asian American and Latino voting behavior. But that trend is changing.

“What we’ve seen among Asian Americans is, over the last several election cycles, they’re voting more and more towards the Democratic Party,” Sadhwani said.

Pan-Asian Influence

That trend is already influencing some redistricting decisions. Texas’s new congressional map reassigned Asian neighborhoods around Houston to a district held by Democratic incumbent Rep. Lizzie Fletcher,

and reconfigured Asian communities in suburban Dallas into a new 4th Congressional District. The result: it’s made Fletcher’s Democratic seat safer, but also protects Republican incumbents in surrounding districts. Latino rights groups are challenging the map in court.

But even when Asian Americans vote for the same party, they can diverge over candidates. In 2016, Rep. Ro Khanna (D), an Indian American, defeated then-Rep. Mike Honda (D), who is Japanese American, in California’s 17th Congressional District. Nearly three-fifths of that district’s residents are of Asian descent.

Those divisions within the community are fewer in states where the growth in the Asian population is a relatively new phenomenon, said Chavi Khanna Koneru, executive director of North Carolina Asian Americans Together, a Pan-Asian social justice organization. That helps coalesce support over a set of common goals.

“One of the things about North Carolina that sets us apart from California and New York and other areas with large Asian American populations is that, because we are smaller, I think there is more room for us to form those coalitions that are in the best interests of the Pan-Asian community,” Koneru said.

“I don’t think that simply having someone who visually represents you necessarily is the best for the community,” she added. “But I do think that having community members who are themselves impacted by these issues, who understand the needs of the community from a very personal place, being able to help them get the training and the recognition they need to put themselves in positions where they can run for office, is certainly important.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Tiffany Stecker in Sacramento, Calif. at tstecker@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Tina May at tmay@bloomberglaw.com; Cheryl Saenz at csaenz@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.