Army’s Aerial ‘Jump to the Future’ Would Replace Iconic Choppers

- Future Vertical Lift is one of the Army’s major priorities

- New aircraft market could be worth $60 billion to $90 billion

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

The U.S. Army is staking its flying future on aircraft that can cruise like planes over vast expanses of the Pacific and Africa, hover like helicopters, evade detection with swift maneuvers, and live out in the dirt.

“We are not just going to have a big biceps—we are going to have full-body fitness,” said Major General Walter Rugen, director of the Army’s Future Vertical Lift cross-functional team. “We can cross oceans; we can cross mountains; we can cross swamps where there’s no roads; we do air assaults; we do delivered attacks; and we do Medevac operations for everybody.”

The Future Vertical Lift program—to replace the iconic Black Hawk and Apache helicopters—is a crucial test to show the Army can modernize without delay and cost overruns, after some high-profile failures over the last 20 years.

The Army wants the new aircraft to fly at least twice as fast and twice as far as the helicopters they’re replacing, the Black Hawk and the Apache, which have been its aerial mainstays since Grenada, Panama, and the first Gulf War. They’ll be in service for decades and fly not just for the Army but also the other military services.

“We are going to fight as a joint force,” Rugen said in an interview. “It is all about being effective in our pacing theaters to be a tremendous deterrent against any peer or near peer threats. And honestly we are becoming obsolete if we do not jump to the future.”

Competing Teams

Despite major investments and overhauls, the military’s vertical lift fleet hasn’t gone through generational change since the 1980s—particularly within the Army, which has the largest fleet, writes Andrew Hunter, director of the defense industrial initiatives group at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank.

For the competing teams led by Lockheed Martin Corp. and Bell Textron Inc., it could be a make or break moment: Winning would cement a foothold as the Army’s aviation provider for decades, and reap the benefits of a market projected to be worth from $60 billion to as much as $90 billion, according to congressional and Wall Street budget analysts.

“It is an opportunity now, because we must modernize for the future,” said Rugen. “The great thing is that Army aviation is at a perfect inflection point: We look far more like coming out of the Vietnam War where our fleets are bought out, and we are able to afford jumping into the future.”

The Pentagon’s ultimate goal is to also replace other aircraft types, ranging from lightweight scout planes to heavyweight transports, such as Boeing Co.’s Chinook CH-47.

Army Defers Boeing Chinooks in Budget Until Later Wish List

“This can help propel the vertical lift industrial base, the rotor-wing industrial base into the future. We need to be designing next-generation platforms,” said Paul Lemmo, president of Sikorsky, now a unit of Lockheed Martin.

“This is important to the industry at large, basically to get our engineers working on these advanced designs—to continue that and get them to production,” said Lemmo, whose company makes the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters.

Long-Range Assault

The Black Hawks have been a mainstay for decades, with their shooting down in Somalia immortalized in the book “Black Hawk Down” by Mark Bowden. And in 2011, a stealth version of the Black Hawk famously crashed during the raid that led to the death of al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden.

Now, with a request for proposals July 6, the Army officially kicked off competition for the Future Long Range Assault Aircraft—just one part of the broader Future Vertical Lift program—to replace the Black Hawks by 2030.

Fights Over Money, Ships, and Planes Set to Lead Defense Debates

Sikorsky, partnered with Boeing Co., are competing for the program against Bell. The Army is expected to select a winner next year to build prototypes for the successor to its 2,000 Black Hawks. The Army already chose Lockheed and Bell for a competitive demonstration phase.

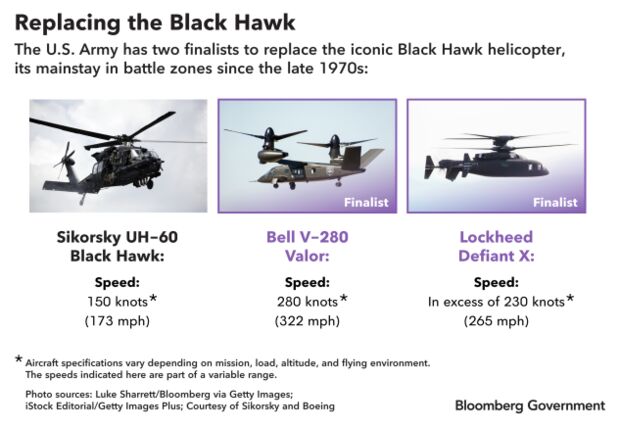

That gives the Army two different aircraft to pick from. One is an advanced tilt-rotor offered by Bell—called the V-280 Valor—which is derived from the V-22 Osprey, with its vertical lift and takeoff technology. The second is the coaxial lift compound rotor helicopter called Defiant X, built by the Lockheed team.

“We are in desperate need of a clean-sheet design,” said Rugen. “Speed range and endurance—that is an exponential increase in capability.”

“We are also vertical lift so we are not tied to an airport. We are not tied to a seaport, and able to be targeted,” Rugen said. “We operate in the lower tier in the air domain so there’s a lot of places to hide.”

V-280 Valor

Bell’S V-280 builds on its experience from the V-22 tilt-rotor, which has been in production since the late 1990s. The fly-by-wire aircraft can top 300 miles per hour and carry 12 passengers. A tilt-rotor aircraft like the V-22 Osprey, the V-280 has engines and rotors at the end of its wings that swivel, which allow it to take off vertically like a helicopter and fly horizontally like an airplane.

Valor is designed to have a cruise speed of 280 knots (322 mph) and a combat range of 500 to 800 nautical miles (580 to 920 miles).

The engine itself doesn’t move like it does on the V-22; just the prop rotor tilts when it goes from vertical takeoff to cruise, or vice versa, explained Bell’s Terry Horner, a director of government relations and Army veteran. The straight wings are easier to build and reduce the manufacturing costs, he said.

“Maneuverability is across the spectrum. We are as maneuverable at high speeds as we are at low speeds,” said Rob Freeland, a Bell government relations director and Marine Corps veteran. “One of the neat things about a tilt-rotor is nothing is turning on the front side or the back side of the aircraft.”

Defiant X

The Defiant X, a team effort of Lockheed’s Sikorsky unit and Boeing, continues Sikorsky’s new helicopter design. Defiant is a compound helicopter—meaning it has an auxiliary propulsion system—and uses twin coaxial rotors to provide lift, and a pusher propeller to enhance speed.

The Defiant X is a larger variant of Lockheed’s Raider X, which is competing for the light-attack program, making commonality a selling point. The propulsion system allows it to fly faster and farther than existing helicopters, CSIS’ Hunter said.

Utility helicopters have to fly low and fast, land quickly, deliver troops, and escape while evading enemy forces and navigating complex terrain. Defiant X flies twice as far and twice as fast as the Black Hawk—but fits in the same operational footprint, or takes up the same amount of space, according to the companies.

The aircraft flies in excess of 230 knots, and the coaxial rotors together with the pusher propeller in the back give it “extra maneuverability,” said Sikorsky’s Lemmo. “That really plays into this whole speed factor.”

“While I won’t say that we will win a drag race against a tilt-rotor aircraft, we have speed where it matters,” Lemmo said. “What matters is the time that it takes to do a mission. Maybe in a straight line we are not the faster platform, but all the maneuvers that have to be done from the beginning of the mission, certainly at the endgame when you get to the ‘X’ (landing zone), that matters.”

Lessons From the Past

Congress allocated $1.13 billion for the Future Vertical Lift program for this fiscal year, and the Army requested $1.56 billion for the effort in fiscal 2022, a 38% increase.

The Army wants to show that it has learned from costly failures in recent decades, and is now focused on “critical technologies and affordability,” said Col. David Phillips, project manager for the future long-range attack aircraft program.

Those costly failures include the Comanche stealth helicopter program, which over 22 years resulted in zero advanced choppers for the Army, the 2004 cancellation of the program, and a $6.9 billion taxpayer bill. In 2009, the Pentagon also scrapped the Army’s most advanced modernization effort—the Future Combat Systems—at a cost of some $20 billion.

Now, Congress has empowered the Army with “extremely important” more flexible buying authorities, said Phillips, referring to non-traditional contracts that enable the military to rapidly buy prototypes or fund research.

Future Attack

The Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft to replace Boeing’s AH-64 Apache helicopters is on a later timeline than the Black Hawk replacement. But Sikorsky and Bell are competing for that one too, with a design fly-off taking place at the end of 2022.

The Lockheed team is offering a scaled-down version of Defiant X, called Raider X, while Bell is pursuing a concept that doesn’t use tilt-rotor technology.

The winners will be replacing helicopters that have helped define the post-Vietnam Army: Black Hawk and Apache choppers fought their way in an out of combat zones for 40 years to deliver and extract troops and supplies, or evacuate casualties.

The Army has “gone to school” on the unsuccessful programs from the past, and teams are now focused on critical technologies and affordability, said Phillips, the project manager.

“What you are seeing underneath the water, as the duck paddles very furiously, is tremendous alignment in the army aviation enterprise,” Rugen said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Roxana Tiron in Washington at rtiron@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com; Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.