Army Steps Up Lures to Recruit Soldiers as Candidate Pool Ebbs

- Army to launch new campaign emphasizing stability, security

- Only about one in four youth is eligible to join military service

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Looking for job security, work-life balance, and paid parental leave? The U.S. Army, confronting a shrinking pool of eligible recruits, is gearing up to make that pitch to potential warriors in an economy disrupted by the Covid pandemic.

“The world has changed quite a bit in the last few years,” Maj. Gen. Alex Fink, the Army’s chief of enterprise marketing, said in an interview. “We see this need for stability and security.”

Deficiencies in education, physical or mental fitness, or criminal records, have exacerbated the Army’s narrowing potential roster of recruits. Out of 34 million people born after 1997, almost 4 of 5 Gen-Zers can’t qualify to serve in the largest military service, the Army’s data show.

The U.S. depends on a strong, all-volunteer military to carry out its foreign policy and defend strategic interests. Military leaders often say that their services are only as good as their people. With operations shifting to the realms of cyber, artificial intelligence, and hypersonic weapons, and China and Russia challenging U.S. leadership globally, the lack of qualified recruits could become a fundamental national security handicap.

“It’s the people that really make our military strong,” said Tom Spoehr, director of the Center for National Defense at the Heritage Foundation. “If we don’t fix these trends, if we don’t turn this around, we are looking at troubled times ahead for the U.S. military.”

A shortage of qualified personnel will start affecting the military’s readiness, Spoehr said, with fewer ships able to deploy, fewer planes able to be flown, and an Army lacking in soldiers needed for its operations.

New Ad Campaign

The Army next month will launch a new campaign to show what it can offer. “It will be very deliberate in highlighting those tangible benefits that the youth are looking for in an employer,” Fink said. “Particularly for us, these are the things that we don’t get a lot of credit for.”

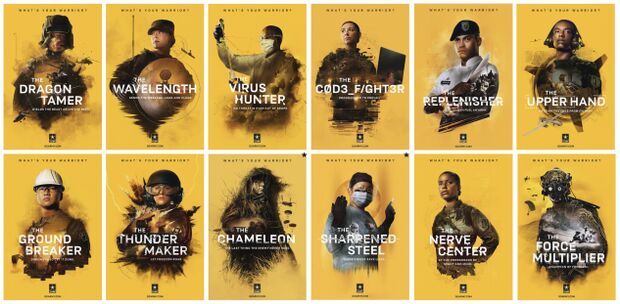

He shepherded two other Army advertising campaigns: “What’s Your Warrior,” meant to change perceptions of the service, and “The Calling,” designed to make the Army appear more accessible and relatable to young people.

Congress has authorized the Army to spend almost $684 million on recruiting and advertising in fiscal 2022, but has yet to pass the annual defense spending bill.

The new pitch aimed a GenZers won’t rely on the long-form, animation, or heavy computer-generated imagery of the other campaigns, Fink said, declining to offer more details.

“It’s a little more fun, it’ll be a little more interesting, different than what you have seen from the Army,” he said.

Omnicom Group Inc.‘s unit DDB in 2018 won the Army’s marketing account with a contract worth $4 billion over 10 years.

Army Anime Courts Teens From a Small Pool of Eligible Gen Zers

Cash Incentives

The Army laid some recruiting groundwork last month with a key sweetener: money. For the first time, enlistees can get a maximum bonus of $50,000 for signing up for six years in such high-demand fields as Special Forces, signals intelligence, missile defense, and fire control. Previously, the top bonus was $40,000.

“Wages are going up,” Fink said. “We want to stay competitive to get the best youth that we can. We have priority jobs that we are trying to fill. There are some jobs that are quite frankly harder to fill.”

The service also has expanded its two-year enlistment options, making it easier for those who may not be comfortable committing to serve four or six years. After basic and advanced training, new soldiers would have to spend only two years on active duty. After that, they would be required to put in an additional two years part-time in the Army Reserve, working with a local unit one weekend a month with a two-week training once a year.

The Army met its sign-up goal of 57,500 active-duty soldiers in 2021, Kelli Bland, director of public affairs for the U.S. Army Recruiting Command. said in an emailed statement. Recruiting goals fluctuate each year, depending on whether soldiers leave or reenlist. The Army doesn’t yet have this year’s recruiting goals, she said. Recruiting has to meet the end goal of 485,000 active-duty soldiers that Congress backed in the fiscal 2022 defense authorization act (Public Law 117-81).

Feeling Depressed

Now, after two years of the crippling pandemic and lockdowns, Army recruiters face additional headwinds attracting and retaining talent as young people re-evaluate their lives and career paths. Half of youths in the Army’s survey say they’re rethinking their careers and education plans, Fink said.

In a broader poll, more than half of 18-to-29-year-olds—a slightly wider group than the Gen-Z pool the Army focuses on— report having felt down, depressed, and hopeless, with a quarter having thoughts of self-harm, the Harvard Institute of Politics fall youth survey reported.

Teen’s Chilling Mental-Health Warning Spurs Senators’ Vow to Act

Half of 18- to- 29-year-olds said Covid-19 has changed them, with a majority saying the pandemic has had a negative impact on their life.

Pandemic restrictions and the economy also have shaped the Army’s recruiting challenges, just as they have for many other public and private organizations, Bland said.

“Our face-to-face contact with the public has been very limited,” she said. “We have expanded our virtual recruiting efforts over the last few years, but we find that a mix of virtual and in-person communication is critical to our success.”

No Awareness

Such contact is critical to meeting another challenge: a lack of awareness of what the Army can offer. About three-quarters of young people know little to nothing about the Army, Fink said.

This newest generation of prospects, raised with technology, the internet, and social media, has had almost no contact or knowledge of the military, which has largely fought wars abroad since 2001.

The Gen Z cohort is also the “most multicultural generation,” with extended families that didn’t grow up in the U.S., didn’t have parents or grandparents who served, and may not have the context to understand what the Army is like, Fink said.

What’s more, a connection to the Army is concentrated in certain regions, particularly in the South, and not so much in the Northeast, West, and now increasingly the Midwest, Fink said.

The growing sense of disconnectedness among potential recruits “is something we talk a lot about within my team and Army at large,” Fink said. “We have a lot of what youth want, we just need to do a better job to communicate that.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Roxana Tiron in Washington at rtiron@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Robin Meszoly at rmeszoly@bgov.com; Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.