Airlines Duck Fines for Busting Wheelchairs (Corrected)

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Wheelchair users have complained for years about airlines breaking their devices, prompting Congress last year to triple the fine regulators could assess for damaging a mobility aid to about $100,000. They also forced airlines to publicly report how many devices they mishandled.

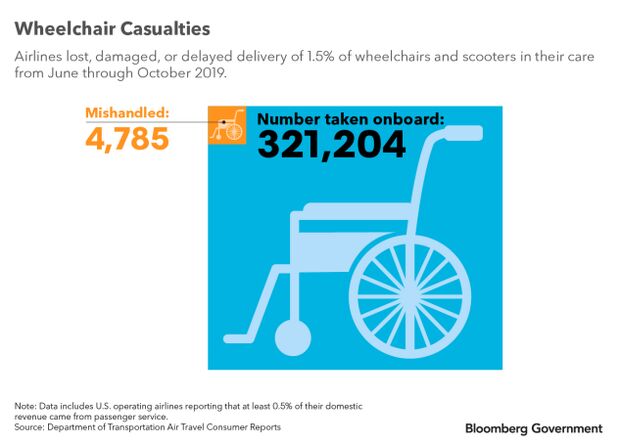

A year later, the Department of Transportation hasn’t issued a single enforcement action using its enhanced powers, even though airlines are, on average, losing or damaging about 1,000 wheelchairs and scooters a month. Several airlines, including Southwest Airlines Co. and American Airlines Group Inc., incorrectly reported their statistics for parts of the year, complicating the DOT’s task. However, the agency said the bad data didn’t impact its oversight of the airlines.

The last time the agency punished an airline for mishandling wheelchairs was in 2016, when it fined United Airlines Inc. $2 million. The fine bundled that violation with others, such as failing to help passengers with disabilities move around terminals.

“The issue is what will it take, and what is the threshold for DOT to take an enforcement action?” said Ian Watlington, senior disability advocacy specialist for National Disability Rights Network. The group, he said, is “pushing for more enforcement actions thinking that once the rules actually start getting enforced, that will truly be the stick that’s needed to have the airlines kind of change their practices.”

The DOT, in an emailed statement, said it issues an enforcement action “where a number of complaints evidence a pattern or practice of violations, or one or a few complaints evidence particularly egregious conduct on the part of a carrier.” The agency takes consumer harm, gravity and extent of violations, and violator history into consideration when deciding to take enforcement action, according to the statement.

Mobility Devices Mishandled

It’s difficult to tell whether the airlines are any better at handling mobility devices since the 2016 fine was issued. At least five carriers didn’t accurately report numbers to the Department of Transportation during parts of 2019, the first year they were required to break out wheelchair data separately from mishandled baggage statistics in monthly disclosures to the agency.

The numbers were so off that the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee sent a letter in November to Airlines for America, Delta Air Lines Inc., and the National Air Carriers Association asking what U.S. carriers were doing to ensure accurate reporting. Airlines for America represents airlines such as Southwest, American, United Continental Holdings Inc. and JetBlue Airways Corp. The committee is reviewing the group’s response to its letter, an aide said.

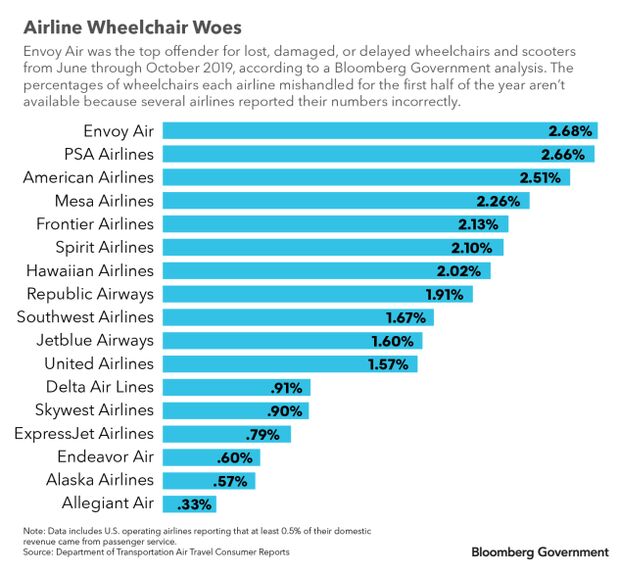

Reliable data exists only from the period between June and October. Airlines collectively reported mishandling about 1.5% of the devices they handled in that span, according to a Bloomberg Government analysis.

Those numbers may be low. Airlines sometimes have deadlines for a person to report a mishandled mobility device after they leave their flight. Passengers may also not report mobility device damage to an airline because the process can be bureaucratic, Watlington said.

The airline with the lowest incidence of mishandled wheelchairs during that period of reliable reporting is one that was subjected to one of the last disciplinary actions the DOT took over disability issues—Allegiant Travel Co. The Department of Transportation fined Allegiant $250,000 in 2018 for failing to correctly help passengers with disabilities move through the terminal and provide timely response to disability-related complaints.

Allegiant has always emphasized mobility device care in its training of customer service agents, station staff, and flight crews, said Keith Hansen, vice president of government affairs, in an emailed statement.

The airline, however, doesn’t offer connecting flights, where baggage and wheelchairs can get lost in transfers.

“You never know if your wheelchair is going to end up in Ohio when you’re traveling to Atlanta and you have a connecting flight,” said Ola Ojewumi, a disability policy activist.

American—which does rely on a system of connections—reported mishandling 2.5% of the mobility devices it handled between June and October. That was the highest percentage among major carriers, and two of American’s regional affiliates, Envoy Air and PSA Airlines, had the most among all airlines.

Workers are now expected to attach a specific bag tag to a wheelchair that differentiates it from a checked bag, Gina Emrich, American’s senior manager for customer accessibility, said in an interview. That feature has helped the airline decrease the number of mishandled devices and improve its reporting to the DOT, she said.

Legislation Pending

The industry struggled most of this year to report correct mobility-device numbers even though the Department of Transportation had delayed the data collection requirement for at least two years.

The agency finalized a rulemaking on the topic in November 2016, and instructed airlines to comply by January 2018. However, the agency later delayed the deadline to January 2019. Airlines for America asked the agency for the delay, according to an email from the group obtained by Democracy Forward, a group that sued the Department of Transportation on behalf of Paralyzed Veterans of America for dragging its feet on the issue.

“Industry is facing some real challenges with both parts of this regulation and will need more time to implement it,” Doug Mullen, vice president of Airlines for America, wrote to Blane Workie, assistant general counsel for aviation enforcement and proceedings, in the March 2017 email.

Airlines for America declined to comment on the record about the contents of the email. In a statement, it said the airlines are “committed” to providing passengers with disabilities the “highest level of customer service.”

The FAA reauthorization law of 2018 (Public Law 115-254) spelled out that the Department of Transportation had to implement the reporting requirement by early December 2018, forcing the agency’s hand on the issue.

The agency now has more data, albeit imperfect, on how airlines handle wheelchairs and scooters because of the law. However, the law doesn’t require the airlines to report details such as where a wheelchair was lost or how badly it was damaged. A House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee aide said more details could help regulators identify patterns.

A Department of Transportation spokesperson said the agency is taking actions outside of enforcement to improve the travel experience for passengers with disabilities. it has developed training materials for handling wheelchairs, mobility devices, and assistive devices and worked with airlines to make sure they accurately report mishandled wheelchairs and scooters. It’s also convened a disability-access advisory committee as required by the FAA reauthorization.

Better Training

Still, there is “rampant mistrust” between wheelchair users and airlines generally, said Emily Ladau, a disability advocate and wheelchair user.

Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wis.) introduced legislation (S. 669) in 2019 that would give wheelchair users the option to take an airline to court over violations of the Air Carrier Access Act (Public Law 99-435), the central law governing how airlines should treat people with disabilities.

Right now, wheelchair users only have two options for when an airline mishandles their chair: report it to the airline, or to the Department of Transportation, said Heather Ansley, associate executive director of government relations for Paralyzed Veterans of America. The Air Carrier Access Act prohibits airlines from discriminating against passengers on the basis of disability, and requires airlines return wheelchairs and mobility aids to the passenger in the condition they received them.

House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Chairman Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.) said the Department of Transportation should create a rule that requires better training for staff who handle mobility equipment, adding that direction from Congress on the topic would force the agency to do the same thing.

“I am type of person who will tell staff who is handling my wheelchair, please take care of my baby, because that’s my legs,” Ladau said.

(Corrects second sentence in third paragraph from end in story published Dec. 23 to specify what airlines are required to do in handling wheelchairs and mobility aids.)

To contact the reporter on this story: Courtney Rozen in Washington at crozen@bgov.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bernie Kohn at bkohn@bloomberglaw.com; Paul Hendrie at phendrie@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.