Abortion-Rights States Begin Shielding Digital Data Near Clinics

- Washington latest to erect ‘geofence’ around health facilities

- Targeted mobile advertising, data collection restricted

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to grow your opportunities. Learn more.

States positioning themselves as abortion safe havens are beginning to shield location information that can be gleaned from mobile phones, and to protect the privacy of other data that can show who is visiting a health-care facility.

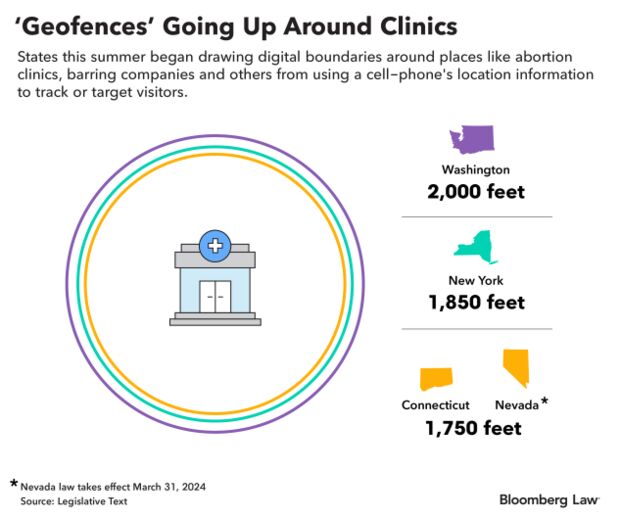

Beginning this summer, Washington, Connecticut, and New York are establishing first-of-their-kind data privacy safeguards for health-related information, in part to prevent anti-abortion groups from targeting people who terminate their pregnancies. A similar Nevada law will take effect next March.

Other states, led by California, are passing or proposing measures that aim to limit out-of-state law enforcement agencies access to certain kinds of data collected by big tech companies like Alphabet Inc. and Meta Platforms Inc.

First-of-its-kind legislation pending before the governor in Illinois would protect abortion seekers traveling to the state from being tracked by out-of-state police using data from license plate readers.

The state policies reflect a growing recognition that traditional legal approaches to keeping medical data private fall short for information held outside health-care settings, such as a doctor’s office, since the Supreme Court last summer struck down a national right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

“Washington was the state that started us out on this trend of passing a health-specific data privacy law,” said Felicity Slater, a legislative policy fellow at the nonprofit Future of Privacy Forum. “It’s gone significantly beyond just responding to Dobbs. States have created new protections for a broad range of personal information.”

Many of the new state policies add safeguards for reproductive health-related information from menstrual period-tracking entries to purchases that might reveal a person’s pregnancy status.

While about half of US states have banned or restricted access to abortion over the past year, six states—California, Connecticut, Maryland, Nevada, New York, and Washington—have enacted laws that would limit the collection, use, or disclosure of private health information, especially data related to reproductive care. At least six other states have considered bills concerning health data-sharing in the past year.

Some of the state measures, including Maryland’s law, try to stem the flow of electronic health records related to medication abortion and other sensitive services without patient consent.

Geofencing Limits

A Washington state provision that took effect Sunday prohibits identifying or tracking individuals if their mobile phone is located at a health-care facility. Location-based targeting typically relies on sources such as Bluetooth, GPS signals, or wireless internet connection points to draw a virtual ring around a particular location, known as geofencing.

The practice is often deployed to direct advertisements toward consumers near retail stores, but it also has been used to send anti-abortion ads to mobile devices located at reproductive health facilities, in an attempt to make pregnant people reconsider their choices.

“People have been using data to surveil pregnancy outcomes for a long time,” said Tristan Sullivan-Wilson, policy counsel for Planned Parenthood Federation of America. “It’s an issue that predates Dobbs.”

Connecticut and New York—along with Nevada, starting next March—are imposing geofencing rules similar to those in Washington. Privacy and digital rights groups have applauded the new state-level protections for location data as a step toward guarding personal health-care decisions.

“Location data is incredibly sensitive,” said Hayley Tsukayama, senior legislative activist at the nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Where we go says a lot about who we are and what’s going on in our lives.”

“It can translate to inferences about health even if it isn’t normally what people think of as health data,” Tsukayama said.

Businesses and other organizations that must comply with these new state laws may face issues with how geofencing restrictions play out, particularly for those that advertise health services using location-based targeting.

The restrictions could have “unintended consequences” for legitimate uses of ad-targeting, such as suggesting at-home care to someone coming out of a hospital, said Kate Black, a partner at Hintze Law PLLC who formerly served as global privacy officer for genetic-testing service 23andMe.

Some ad-targeting platforms already have policies to protect visits to potentially sensitive locations. Data broker Kochava has added a “privacy block” feature that removes information from its data marketplace for places categorized as health-care services in the US.

Google has pledged to delete location history entries from counseling centers, domestic violence shelters, abortion clinics, fertility centers, addiction treatment facilities, and other places where services provided can be particularly personal.

State Spread

Once the laws in Washington, Nevada, and Connecticut go fully into effect, people covered by the measures will have some of the broadest privacy rights over their personal health data in the country, with new requirements for gaining their permission before collecting or sharing personal information and rules for storing data securely.

The information protected varies by state, but each law generally covers any personally identifiable information used to associate a consumer with their physical or mental state, such as information stored in a period-tracking app.

Washington’s health privacy law is considered the widest in scope, extending to protect data that could be used to draw insights about an individual’s health status when combined with other information. It’s meant to cover situations such as a retailer predicting that a shopper is pregnant based on the purchase of certain products.

Each state’s attorney general will enforce violations of the new health privacy laws, and can impose fines in the thousands of dollars per violation. Washington’s measure is the only one that also empowers individuals to sue over health privacy issues via a private right of action that could yield as much as $25,000 in damages per violation.

That provision, and most of Washington’s law beyond its geofencing provision, will take effect March 31, 2024. Nevada’s law also will be effective on that date. Connecticut and New York’s health privacy protections are already active.

Looking Ahead

Health data a patient shares in a medical context with doctors or health insurers is protected by the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, known as HIPAA. Apps or websites that gather health-related information, such as a period-tracking platform, generally aren’t covered by the nearly three decade-old health privacy law.

Dobbs spurred the US Department of Health and Human Services to propose an update to HIPAA that would limit the information law enforcement officials can access about individuals seeking reproductive health care. Providers in states where abortion is legal wouldn’t have to honor a request for patient records from out-of-state authorities under the proposal.

Lawmakers in a handful of states have proposed or passed legislation that likewise aims to block out-of-state law enforcement agencies from leveraging medical records and other digital health-related information to investigate abortions deemed illegal in other jurisdictions.

This issue was illustrated by a case in which a Nebraska woman was charged with two felonies related to an allegedly illegal abortion after authorities found information about the pregnancy in private messages on Meta’s Facebook Messenger app. Law enforcement officials used a search warrant to obtain the messages, though the warrant didn’t mention abortion.

California last year barred companies such as Meta and Google’s owner Alphabet from turning over user messages or searches to law enforcement agencies in other states that seek to bring cases against abortion seekers. Washington state and New York adopted similar policies this year.

These measures could create a legal quandary for companies that face conflicting directives from different states, putting businesses in “the crosshairs of political views,” according to David Zetoony, co-chair of Greenberg Traurig LLP’s privacy practice.

“They’ve set up an impossible situation where the company is going to get a demand from a government that restricts abortion for health information, and the company’s going to have to comply with that request, or they’re going to have to comply with the Washington state law,” Zetoony said.

To contact the reporters on this story: Andrea Vittorio in Washington at avittorio@bloombergindustry.com; Skye Witley at switley@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com; Tonia Moore at tmoore@bloombergindustry.com

Stay informed with more news like this – the intel you need to win new federal business – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.