Puerto Rican Farmers Fight Climate Change That’s Destroying Them

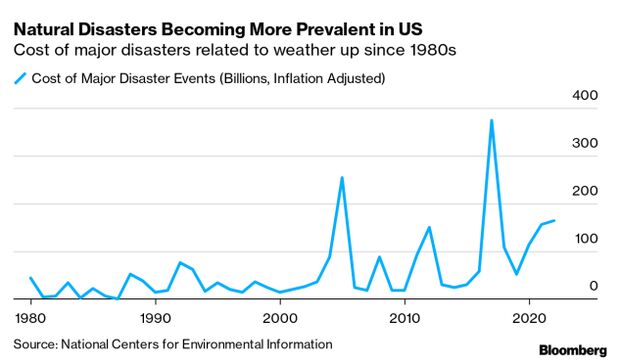

- Increased natural disasters hit farmland across country

- USDA is urging farmers to use climate-smart practices

Bloomberg Government subscribers get the stories like this first. Act now and gain unlimited access to everything you need to know. Learn more.

Puerto Rico lost 80% of its coffee trees after Hurricane Maria. Just five years later, two more hurricanes threw a wrench in coffee farmers’ recovery.

“Maria was something we had never seen in our generation,” said Jorge Sanders, a consultant for Puerto Rico Coffee Roasters. While federal aid lagged, nonprofits like the Productores de Café de Puerto Rico, or Procafé, organized to distribute seeds to farmers so they could rebuild their operations.

When Puerto Rican farmers started regrowing, they knew severe weather events weren’t going away. So, Sanders said, they used smarter practices.

Puerto Rican growers’ plight highlights an obstacle faced by farmers across the US: how to maintain production when each year brings more extreme weather events. Farmers hit by climate change are calling for more federal aid. They’re also adjusting their farming methods to stay ahead of the trend, including making operations more sustainable.

Puerto Rico’s frequent storms and other natural disasters put its farmers in the vanguard of rebuilding agriculture in a more sustainable way.

“We were left with a blank canvas” after Hurricane Maria, said Sanders. “We could paint the canvas, and what we all decided was, ‘We need to paint this right.’”

Resilient Farmland

Puerto Rico doesn’t come close to growing as much coffee as major producers like Brazil or Vietnam, but the crop is a key part of the island’s culture and local economy. Over 21,000 hundredweights, a unit used to measure commodities, of coffee were harvested on the island in 2017, according to the most recent Agriculture Department census.

The island’s growers hope to become major players in coffee akin to Brazil, Colombia, and Ethiopia. That means regrowing the coffee trees they lost and then some. Maximizing soil health and yields through practices like planting cover crops and growing in horizontal rows to reduce runoff will be key to that mission.

“You need to use it in a way that’s productive for you but is still going to be there for the next generation,” Sanders said of the island’s farmland. One way of doing this is using inputs like “biochar,” a waste compost product that can be added to soil to better retain nutrients. Improving soil health with biochar boosts farmers’ yields and makes them more resilient to extreme weather. Plus, biochar helps sequester carbon in the soil, an added bonus for the climate.

For the island’s coffee farmers, resilience also means reducing chemical use to improve soil health and planting in patterns that reduce erosion, Sanders said. In the mountainous countryside where the bulk of the island’s coffee crops are grown, limiting soil erosion could make all the difference in avoiding another coffee tree catastrophe.

The hope is sustainable practices can grow production — and ensure the next disaster doesn’t wipe them out again.

‘We Have No Option’

The Department of Agriculture wants all US farmers to heed that message. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack traveled to a coffee farm in Jayuya, Puerto Rico, earlier this month to urge farmers to adopt climate-smart practices to make their products more resilient while mitigating climate change impacts.

Such practices include planting cover crops, applying precision agriculture to use fewer inputs like fertilizer, and using feed additives to reduce methane emissions from cows — all things the USDA has funded as part of its pledge to make farming more environmentally friendly.

“We have no option” but to use more climate-smart agricultural processes, said Germán L. Negrón-González, general manager for Puerto Rico Coffee Roasters. “We have been hit by climate change,” severely, over the past few years, he added.

Agriculture is responsible for over a tenth of carbon emissions in the US, making it one of the top industries contributing to greenhouse gasses. But efforts to cut agriculture’s carbon footprint tend to divide farmers, who can be wary of policies that would impede their ability to produce food.

Vilsack last week sought to convince farmers otherwise.

“The challenge is to figure out ways to keep farmers in business and make it profitable — not just productive — but profitable, sustainable, and resilient,” Vilsack said.

For starters, Vilsack said, farmers can advertise their products as climate-smart to earn a higher price on the market. Over half of 1,988 registered voters surveyed in an August Morning Consult poll said they’d prefer farmers using sustainable practices that will avert food shortages for future generations, rather than maintaining current practices to keep food prices down. The poll was conducted on behalf of the Walton Family Foundation, which the founders of Walmart Inc. started.

Another revenue stream for farmers using climate-smart practices could be carbon markets that pay operations for sequestering greenhouse gas emissions, Vilsack said. Generating and selling carbon offsets “creates a new revenue stream, a new market opportunity, a new commodity,” he added.

Divisions in Congress

The Growing Climate Solutions Act from the last Congress would have ordered the USDA to create protocols for such a voluntary environmental credit market for farmers. Though the bill passed easily in the Senate with bipartisan support, it stalled in the House, with some opposition from environmental groups that said monetizing carbon sequestration wouldn’t get to the root of climate change. Lawmakers might try to attach a similar measure to this year’s farm bill.

Despite broad bipartisan support for carbon markets and conservation funding, climate-smart agriculture has already caused a stir among Republicans. Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-Calif.) in September criticized the USDA’s Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities program, saying the agency released the more-than-$3 billion “with no mandate, direction or authorization from Congress on how to distribute it.”

House Agriculture Chairman GT Thompson (R-Pa.) has been supportive of voluntary conservation funds, but cautioned against mandates for sustainable farming like the European Union’s Farm to Fork Initiative. If the entire world adopted the EU’s required reductions on inputs like fertilizer and pesticides, global food prices would increase 89% and production would fall 11% by 2030, the Agriculture Department found.

“I have been leaning into the climate discussion, but I will not have us suddenly incorporate buzzwords like regenerative agriculture into the farm bill or overemphasize climate within the conservation or research title, while undermining the other, longstanding environmental benefits that these programs provide,” Thompson said, previewing partisan fights over measuring conservation programs by their climate benefit in the farm bill.

Compounding Challenges

In addition to dealing with disaster-prone land, Puerto Rico’s farmers face unique challenges, with the territory’s recent bankruptcy complicating residents’ ability to get disaster aid.

“You take a situation that’s already complicated, programs that are already complicated, and you lay it on top of a place that’s highly disorganized, lack of capacity, was in bankruptcy — there’s a lot of risk,” said Chris Currie, director of Homeland Security and Justice for the US Government Accountability Office. “Unfortunately, it’s kind of played out exactly in the way that we hoped it wouldn’t have.”

A GAO investigation found the lion’s share — 81% — of Federal Emergency Management Agency funding for Hurricane Maria relief in Puerto Rico hadn’t been spent by August 2022. The watchdog called recovery from Maria in 2017 the “largest and most complicated in our nation’s history.” Reduced agency staffing on the ground, in part due to fewer available government funds post-bankruptcy, made the process of getting money out more disorganized, the GAO found.

The territory also couldn’t take out debt after its bankruptcy, which some US states rely on to jumpstart recovery projects before getting federal money, Currie said.

Specialty Crop Challenges

Puerto Rico farmers’ finances are also complicated by the particularities of crop insurance, which farmers rely on as a more consistent alternative to disaster aid.

The bulk of US agricultural production is in corn and soybeans. This means specialty crops, like fruits and vegetables, tend to receive less risk coverage from insurers and government agencies than more common crops.

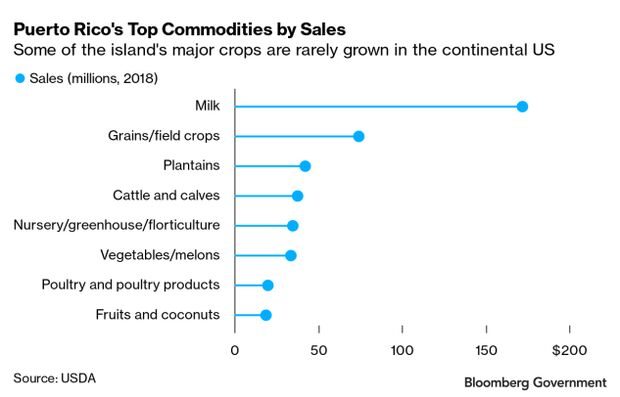

But those specialty crops are exactly what Puerto Rico specializes in. Milk is the island’s top commodity, but other top sales come from plantains and other fruits and vegetables, according to USDA data from 2018, the most recent available.

The American Farm Bureau Federation, the largest agricultural lobbying group in the US, made extending specialty crop coverage one of its top priorities ahead of the 2023 farm bill. The group sells crop insurance and wants to ensure ad hoc disaster aid doesn’t impede on private insurance.

But specialty crop growers tend to have fewer crop insurance options, making ad hoc disaster assistance especially critical for them.

“When a hurricane comes through, they’re looking for options to protect themselves,” said Danny Munch, an economist at the Farm Bureau. “In many cases, some of those crops aren’t going to be covered.”

Federal aid can make all the difference for people like Asier Roldan, who lost his entire banana crop in the south of Puerto Rico to hurricanes last year. Bananas are especially vulnerable to heavy winds because their shallow roots can get swept out of the ground easily.

Crop insurance is “ a slow process that takes a lot of time,” Roldan, the president of Bananera Costa Sur, said. More federal ad hoc disaster aid is needed in Puerto Rico, he added, because”often we don’t get paid what we should get paid.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Maeve Sheehey in Washington at msheehey@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Anna Yukhananov at ayukhananov@bloombergindustry.com; Sarah Babbage at sbabbage@bgov.com

Stay informed with more news like this – from the largest team of reporters on Capitol Hill – subscribe to Bloomberg Government today. Learn more.